Table of Contents

For Mom and Dad,

who encouraged me to be interested in interesting things.

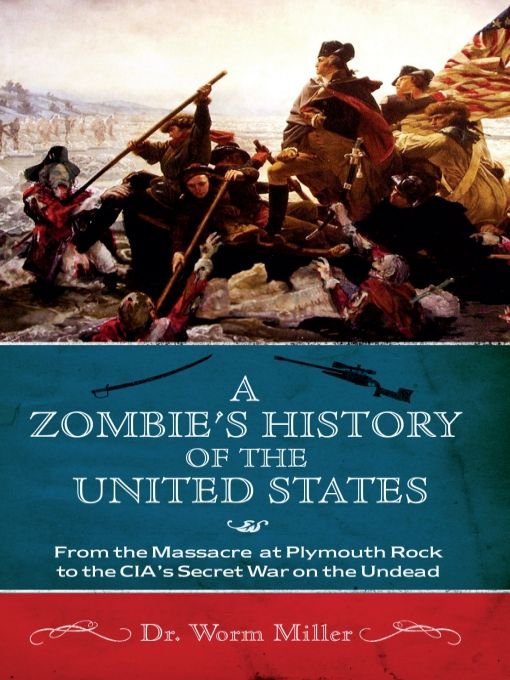

No, I am not undead.

I am a human and an American.

One who loves history and wants to see it told right.

My only bias is for the truth.

Dr. Worm Miller

Prelude of the Living Dead

AN INTRODUCTION TO ZOMBIES IN AMERICA

If you would understand anything, observe its beginning and its development.

Aristotle, Greek philosopher (384-322 BC)

Zombie is the accepted modern term, or zomboid if one wishes to be clinical, but the mobile dead have been called many different things over the centuries

The undead, the living dead, the walking dead, walkers, wraiths, ghouls, demons.

These names palpably conjure the superstition and the fear of early European settlers trying to comprehend what these strange, new, dangerous creatures were. Over half a millennium later, we still do not have all the answers. Our scientists now understand the biological properties of the human zombination virus, how it works, how it spreads, and how to manipulate it; yet, we still know as little of the contagions origins as the Pilgrims did.

This Homo Neanderthalensis skull, found in France in 2005, is approximately 60,000 years old. Some zombologists have proposed that the mysterious bite marks on the skulls braincase are those of a zomboid. If this is true, it would mean that zombism is much older, and covered a much greater area, than anyone ever imagined.

For most of the 20th century, scientists believed that the contagion was zoological in origin, that early humans contracted it from now extinct megafauna upon arriving in North America between 16,000 and 20,000 years ago. That is, until a shocking archeological discovery in 1993 challenged the conventional wisdom that zombies were native to our continent.

A dig seventy miles west of the city of Anadyr in the northeasternmost corner of Russia, co-sponsored by the University of Minneapoliss Zombological Department (UMZD) and the Moscow Center for Sciences, uncovered the skeletal remains of eight humans (four adult females, three adult males, and one female child). The remarkably well-preserved remains were riddled with human teeth marks, telltale signs of zombie devourment. This alone could have been dismissed as merely evidence of cannibalism and nothing more, but a mass grave was also uncovered at the site that contained thirteen other bodies, all of which had been either decapitated or otherwise cranially assaulted. Ash from the sediment indicated that the mass grave had served as a fire pit, meaning that the bodies had been burnt. These had surely been zombies. Most shocking of all, carbon dating placed the remains at roughly 17,000 years old.

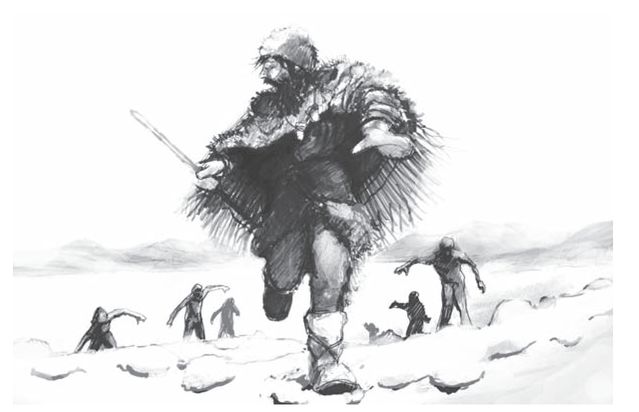

Supporters of Thadds Michaelssens Asian origin theory believe that the reason ancient humans chose to cross the Bering land bridge into North America was because of the sudden appearance of zombies in Asia around 17,000 years ago.

The Anadyr find was the culmination of almost two decades of work for the University of Minneapoliss Tom Ringdal, who has been a lifelong subscriber to 20th century Norwegian zombologist Thadds Michaelssens controversial theory that zombism originated in Asia, not North America. Now Ringdal had what Michaelssen never did: evidence. Ringdal believes that the emergence of zombism in upper Asia some 17,000 years ago was in fact the catalyst that drove ancient humans into North America via Beringia, also known as the Bering land bridge, which connected present-day Siberia and Alaska during the low sea levels of the Pleistocene ice ages.

Detractors of the Asian origin theory counter that humans were already living on Beringia by that time, and that the Anadyr zombies had simply moved westward from Alaska seeking new prey. For if zombies had truly emerged in Asia, where did they all go? What prevented them from spreading throughout the rest of the Eurasian landmass and into Africa? Michaelssen theorized that if humans were moving eastward into North America, zombies would inevitably follow their food source, having little incentive to venture westward, and eventually the contagion became isolated when sea levels rose again, re-separating the continents. Ringdal has always been quick to point out that the Anadyr remains predate the oldest zombological evidence in North America by more than five hundred years. Of course older evidence, which tips the scales back toward a North American origin, could be discovered in Alaska or Canada by the time this book hits shelves. This sort of science is only as permanent as the latest discovery.

The truth is, even if we could conclusively determine where zombism began, it likely will not answer how it began. Theories on the how/why of zombies are as varied as they are plentiful. Some have proposed that the contagion was the result of generations of cannibalism, sort of a mad cow disease for humans; devout Christians have long seen zombies as the work of the devil; the Crow Indians believed zombism was a punishment from their trickster god for those who, cowardly, feared death; and there will surely always be those who are convinced that zombism is of alien origins.

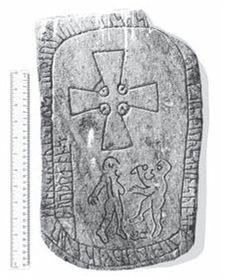

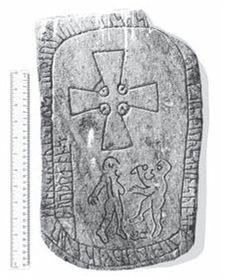

If only those first humans who found their dead rising up against them had been able to preserve their history, what grave and revealing stories they might tell us. As is, our preserved record of zombism barely goes back a thousand years. The Vikings were with all probability the first Europeans to encounter zombies. These hardy explorers kept no records either, though the Icelandic saga collection, Hauksbk, retains much of the Viking oral history. Saga of Erik the Red, which chronicles the events of Scandinavian legend Erik the Reds banishment to Greenland, as well as his son Leif Ericsons attempts to settle present-day Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada, contains several references to a vicious tribe living in the New World, which the Vikings referred to as vttrs, or monsters. It was these vttrs who prevented the Vikings from establishing a permanent settlement in North America. A Norse runestone dating from the period (uncovered in Greenland in 1914) depicts a Viking fighting with an vttr, who is portrayed as being badly dismembered. Surely these were zombies the Vikings clashed with there.

This Viking runestone, circa 1040 AD, found on Kullorsuaa Island in northwestern Greenland in the 20th century, depicts a male Viking battling a treacherous vttr. Many scholars believe this to be the earliest known European record of a zombie.

Fortunately for us, the next round of Europeans to reach North America some five hundred years later kept fairly thorough records. Doubly fortunate for us has been the efforts of the University of Minneapolis to preserve these records.