THE

MIGHTY

FALLEN

OUR NATIONS GREATEST WAR MEMORIALS

Larry Bond f-stop Fitzgerald

TABLE OF CONTENTS

WAR AND PEACE

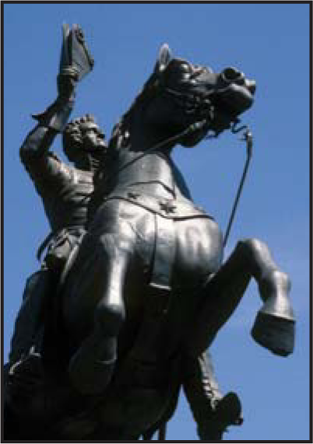

Monument Park in Baltimore, Maryland began as a single memorial to our recently-deceased President George Washington. A 160-foot-tall marble column was no less than the first president deserved, but city residents were worried about it falling, so the work was erected north of town. As time passed, the city grew toward and around the park, and the park became a place for other memorials. A statue of Lafayette honors the ties between France and America in WW I. A philanthropist, a Supreme Court justice, and others were all honored.

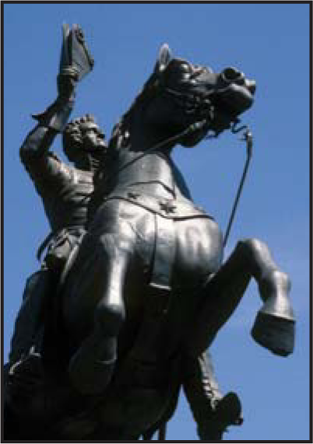

French sculptor Antoine-Louis Barye created four statues depicting War (see detail above), Peace, Order, and Force. They were donated to the city in the 1880s.

INTRODUCTION

BY LARRY BOND

An old battlefield gives no hint of the struggle that took place there. A great campaign might have been won or lost, but human affairs make little impression. Defensive works or scars from shellfire are quickly softened by nature. The land may even be returned to its original use. Even in carefully preserved national parks, like Gettysburg, the land alone will not tell the story.

The passage of time is even harder on human memory. The moment the battle is over, actions begin to fade in the participants minds. Once the debris is cleared away, only people can preserve the events. Paper records, photos, audio, and video recordings can help, but to someone who has been there, they are a pale fraction of the real thing.

Memories of a war or battle are unpleasant, but few veterans would want them erased. That part of their life was important, serving an end larger than themselves. And the goals always require sacrifice. Their hardships and their friends suffering are meaningless without some goal or purpose. Victory obviously provides that validation, as does defeatthough perhaps less soif their cause was worthy.

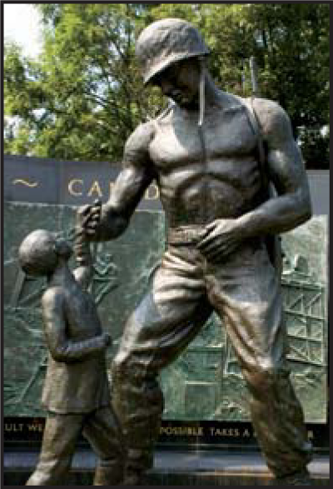

Veterans have always known that their deeds and the sacrifice of their comrades would be lost with their own passing. Each wartime generation has commissioned memorials and monuments. Many are built on the battlefield. Some are built in the homes they left. Their very name, memorial, hints at their first purposeto make sure the events that took place are kept in our memories. But beyond information, they also want us to remember that there was a cost. That is their second goal.

Losses are felt deeply by those who fought together. They know each other well, and have shared much, often more than those at home understand. A wartime death also takes away someone before their time, and their death may be hard. Even in triumph, a veterans first thoughts will be of those who didnt live to see it.

So when veterans erect a memorial, they include names. In fact, one of the most recent and most famous of memorials, the Vietnam Veterans Memorial on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., is nothing but a list of namesthe name of every American who was lost fighting in that conflict. It is a moving experience to visit that place, and it should be.

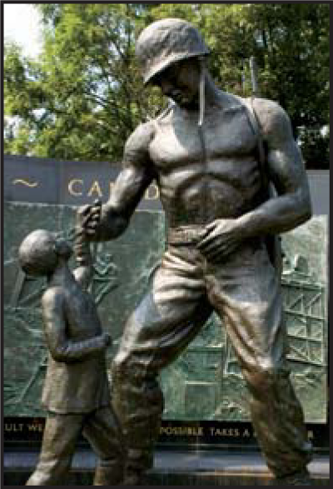

The third and most important purpose of a monument is to move us, to evoke emotions. Those feelings can only be hinted at by a book, a photo, a film or a video. They can be grief, fear, anger, or pride, or other more complex emotions, but the people who create a memorial want us to know what they knew, and feel what they felt.

A memorial is almost always the work of an artist; while few people describe war memorials as beautiful, they do describe them as powerful or moving. Art evokes emotion, and good art creates strong ones.

The Mighty Fallen uses photographs to show what the memorials designers wanted us to know about their creations. We have selected images of monuments from all of North America, both in the United States and Canada. They cover wars in three centuries, the eighteenth, nineteenth, and twentieth. The memorials presented are arranged in an approximate, chronological order by conflict within each century.

It is not a history of military monuments or a complete survey of North American memorials. The images in the book were chosen for their artistic significance and their effectiveness at communicating their creators message. Some images show the complete monument, some only a detail. Each is an interpretation of that memorials spirit and message from its creators to us. It is only one interpretation.

The need for remembrance has been a constant. Sometimes groups or individuals have been overlooked or shortchanged; others will hopefully receive their fair share.

Our way of building memorials has not changed much, either. Both the Revolutionary Monumentthe first war monument built in this countryand the Vietnam Veterans Memorial are simple shapes listing the names of the dead. Individual honors usually rate a statue, and those dedicated two hundred years ago look as modern as ones cast today.

It should be comforting that the way we memorialize our heroes hasnt changed: memorials built centuries ago still perform their purpose; those we erect tomorrow will honor the mighty fallen for generations to come.

We owe it to them to remember.

A mericans have always had a special relationship with their fighting men and women. In eighteenth-century Europe, professional armies fought the wars. They were relatively small, but extremely disciplined. Troops needed discipline to stand in tightly-packed ranks while enemies within shouting range fired murderous volleys and their companions fell around them. That discipline was iron-hard. It was better to be shot at than risk punishment for breaking ranks.

Discipline was also necessary because most European professional soldiers were either the dregs of society or mercenaries. Many would desert, given the chance. A lot of staff work was devoted to preventing opportunities for desertion, and rounding up the inevitable stragglers. Often the soldiers and sailors were criminals.

During the Revolutionary War, General Washington would work to create a regular army, with the help of expert European officers like Casimir Pulaski and the Marquis de Lafayette. The result was not a European-style army. European tactics didnt work on American battlefields, and American soldiers hadnt been press-ganged.

In addition to regular troops, American colonial soldiers were local men who served either in the volunteers or militia. Volunteers wore uniforms and had names like First Pennsylvania or Third Massachusetts. They were expected to join the line of battle and fight as regular troops. Militia were local folk mustered in an emergency i.e. The Minutemen. They acted as scouts and skirmishers, and usually wore civilian clothes. Neither type was as well-trained or disciplined as regular army units, and professional soldiers didnt bother hiding their contempt.

Next page