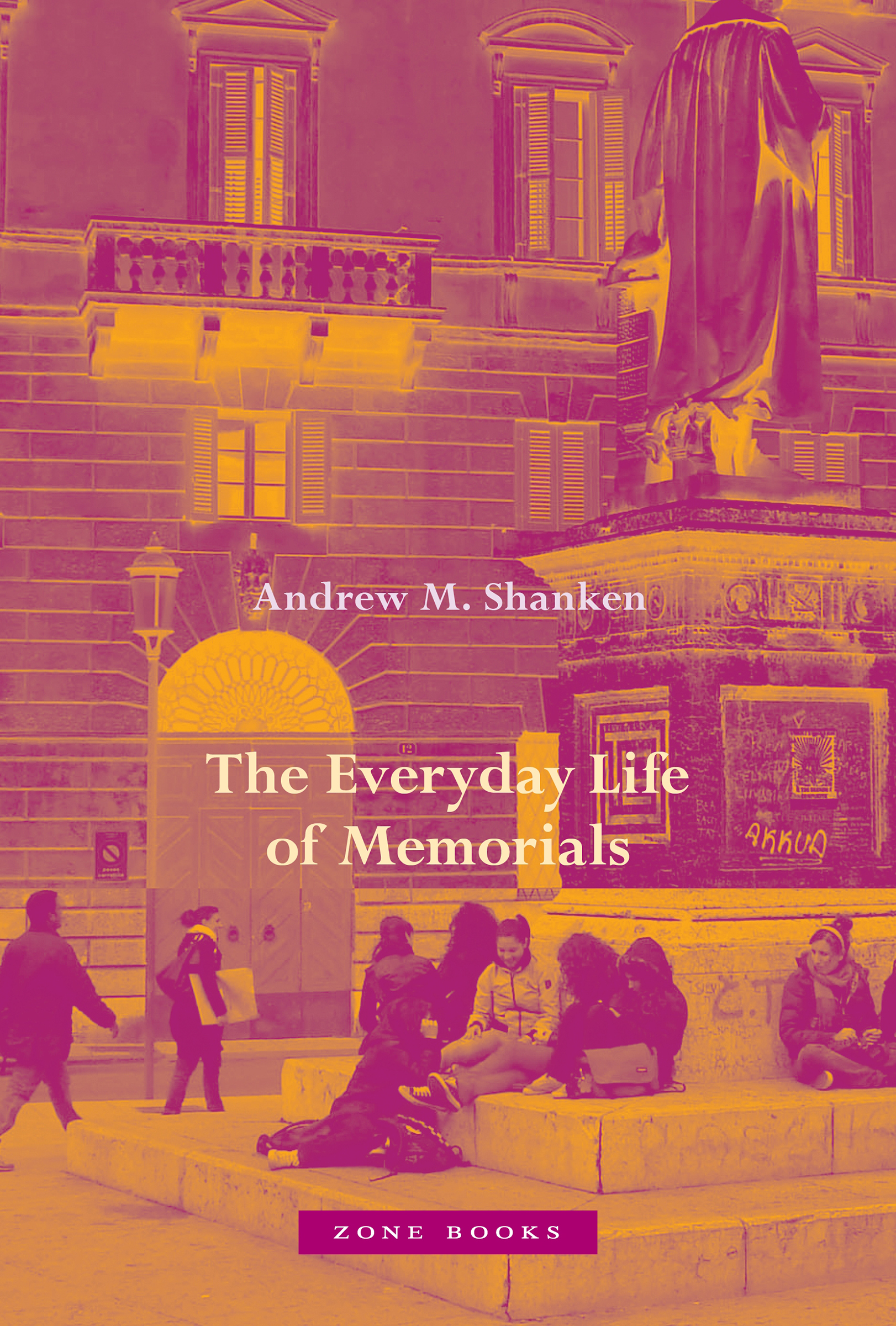

The Everyday Life of Memorials

The Everyday Life of Memorials

Andrew M. Shanken

ZONE BOOKS NEW YORK

2022

2022 Andrew M. Shanken

ZONE BOOKS

633 Vanderbilt Street

Brooklyn, NY 11218

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including electronic, mechanical, photocopying, microfilming, recording, or otherwise (except for that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the Publisher.

Distributed by Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey, and Woodstock, United Kingdom

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Shanken, Andrew Michael, 1968 author.

Title: The everyday life of memorials / Andrew M. Shanken.

Description: New York : Zone Books, 2022. | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Summary: This book works with the literature of the everyday, memory studies, and non-representational geography to open up a novel understanding of memorials not just as everyday objects, but also as fundamental to urban modernityProvided by publisher.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021062586 (print) | LCCN 2021062587 (ebook) | ISBN 9781942130727 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781942130734 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Memorialization. | Memorials. | Sociology, Urban. | Collective memory. | Public spacesPhilosophy.

Classification: LCC D16.9 .S4575 2022 (print) | LCC D16.9 (ebook) | DDC 394/.4dc23 / eng/20220120

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021062586

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021062587

Version 1.0

Contents

Preface

Monuments possess all sorts of qualities.

The most important is somewhat contradictory: what strikes one most about monuments is that one doesnt notice them.

There is nothing in the world as invisible as monuments.

Robert Musil, Monuments, 1927

This book went through multiple incarnations, each with its own working title that offers a peephole into the process of its making. It started in 2006 as A Cultural Geography of Memorials. I saw in the ideas of writers such as Lorimer, Nigel Thrift, Trevor Pinch, Bruno Latour, Maria Kaika, and others a way of understanding how people engage with memorials that other fields had not been able to fathom. Put differently, I did not think that Robert Musils denigration of monuments as being invisible, which serves as the epigraph here and as a point of reference throughout, meant that they were any less present. What better method to see monuments anew than one that could venture beyond the visual?

This range of concerns, sometimes assembled under the intimidating term nonrepresentational theory, would seem to be an enemy of art history and the object.

This attempt to rescue formal analysis from unnecessary violence was neither reactionary nor retardataire. A rapprochement between formal analysis and nonrepresentational theory should not be a paradox. The analysis of form in art, and especially in architecture, implicitly posits a relationship between objects and people. In its most deliberate and politically engaged formulation, form is seen as a form of social reform, a means of enacting social change. This modernist faith in a kind of material determinism was born of sentiment and faith deeply hidden behind mechanistic and moralizing language. The house may be a machine for living in, as Le Corbusier famously said, only after a renunciation of sentiment that is itself a sentiment of the strongest sort. While unreconstructed modernists still walk the earth, architectural historians can now historicize this arch position as a feeling. The urge to historicize the memorial within similar notions of cultural sentiment while looking closely at their form, placement, and interaction with people and cities prompted me to attempt to reconcile formal analysis with cultural geographys phenomenological turn.

Memorials provide a test case because more than most objects, they come laden with the invisible elements that enthrall recent non-representational geographers while being complex objects formally. They are auratic, changeful, seized by the episodic, and blurred by urban flows. They offer a paradox as well: in response to the same forces that birthed the new cultural geography, they have increasingly taken forms that defy formal analysis. In extending formal analysis to a larger field of observation, a cultural geography of memorials would look not just at the physical fact of the city, but also to the material reality animated by use or quieted by disuse. The monument, in other words, cannot act alone. It cannot shoo away the ubiquitous bird on its head or banish the traffic snarl that consumes it in honking, exhaust, road rage, and a melee of signs and commercial gestures. These interventions of nature and culture may not have been part of the intention, but they end up being central to the experience of memorials. In addition to the seemingly incidental and accidental accumulation of the everyday, memorials often contend with other memorials that divert, distort, and reorient them, ushering older memorials into newer scenes. In turn, the additive quality of memorialization, in formal terms and in practice, alters the performance of the entire space in a dance of people, objects, and places.

Over time, as I encountered thousands of memorials, nonrepresentational geography became less central. I began to see memorials as oddities: curious, comical, at times ridiculous or grotesque, and at their most extreme, freakish. In positive terms, they are a form of bizzarerie. As Henri Lefebvre writes: The bizarre is a mild stimulant for the nerves and the mind. As a stimulant and tranquilizer, bizzarerie is a risk-free experience, a pseudo-renewal, obtained by artificially deforming things so that they become both reassuring and surprising). A better description of many memorials would be hard to craft, yet it misses something specific about memorials, which are not always risk-free or tranquilizing. Conventionally, they are made to step outside of their time and place. Frequently, they advance, whether stridently or blithely, with assertive manners and quickly outdated styles. They are fashioned of expensive, permanent materials such as marble, bronze, or granite and plopped down statically in a world hell-bent on change. They are then lifted above the fray, made larger than life, and maintained as strictly noncommercial, even though nearly every other part of Western culture has been monetized. (Some memorials have succumbed, of course.) They are public amid a long slide toward the privatization of everything. Perhaps their most aberrant quality is that they are often intended as mnemonics of loss, death, disaster, and trauma in settings ill-suited for such darkness.

Figure P.1. An eerie Greek helm on a death mask and hot-blood-red names are now all the stranger since the former cemetery became a verdant park in a housing complex. Napoleonstein, 1836, Kaiserslautern. Courtesy of Kumbalam.

Figure P.2. Self-conscious bizzarerie in cartoonish baroque. Marten Toonder Monument, Den Artoonisten, designers, 2002, Rotterdam. Photograph by Wikifrits.