Contents

Pagebreaks of the print version

Guide

For Cameron and Finn and Cole and Hazel

For K

And for my teachers and classmates

at Columbus School in 1974 and 1975

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

KRISTIN ANN HASS teaches in the Department of American Culture at the University of Michigan. She is the author of Sacrificing Soldiers on the National Mall, a study of militarism, race, and US war memorials, and Carried to the Wall: American Memory and the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, an exploration of public memorial practices and the legacies of the Vietnam War. She holds a PhD in American studies and has worked in several historical museums, including the National Museum of American History. She was also the cofounder of Imagining America: Artists and Scholars in Public Life, a national consortium of educators and activists dedicated to campus-community collaborations, and she is currently the faculty coordinator for the University of Michigan Humanities Collaboratory.

SECTION I

MEMORIALS

MONUMENTAL BASICS

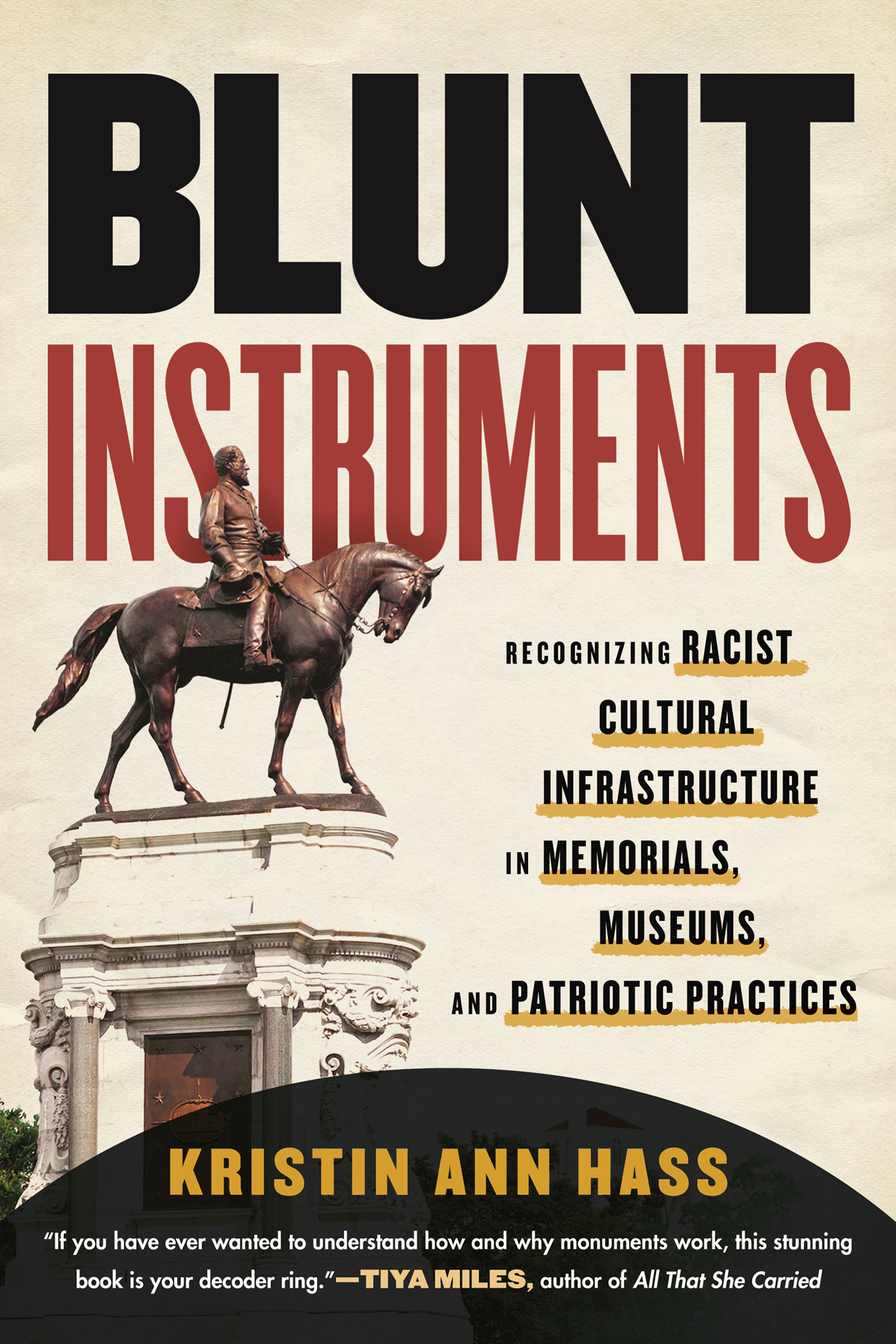

A photograph of the Strom Thurmond Monument on the grounds of the state capital in South Carolina shows a figure of a man caught mid-stride, still in action. A photograph of the inscription on one of the panels on the memorials base shows how hard it is to change the logics we inscribe in our landscapes. These photographs are a useful place to start an exploration of memorials and monuments because they evoke a compelling set of questions about our shared public landscapes across the United States. (See .)

As you look at these photographs, you see a very familiar form in which something is not quite right. In the background of the first image, the neoclassical architecture of the South Carolina state house and its white pillars, stone steps, and domed rotunda are all familiar elements of traditional civic architecture. (Exactly the elements that the Making Federal Buildings Beautiful Again executive order sought to require going forward.) The figure in the foreground is also familiar: a man on a stone plinth. In this case, the man is Strom Thurmond, the longest-serving member of the United States Congress and a life-long full-throated segregationist. It is in the close-up of the plinth that something appears to be wrong. The word five is a mess, a rough disruption of the clean and controlled text. The engravers had the difficult task of turning four into five when Essie Mae Washington-Williams asked the state of South Carolina to add her to the monument. She was the mixed-race daughter of Thurmond and Carrie Butler, a young domestic worker in his parents house. While he was alive, Thurmond kept secret the fact that he had a mixed-race child. After his death, she came forward and asked to be added to the monument. She put herself into the landscape, but it was not easy to do. First she had to ask the state, and approval from the state senate was required to make the change. But, more significantly, she had to insert herself into a visual and symbolic vocabulary that was organized to exclude her: to keep the very idea of her, the possibility of her, hidden. This is a big claim to make, but a little information about memorials and monuments in the United States should make it pretty easy to support. The jagged five raises a question about how we fit a carefully repressed perspective into an existing landscapean existing symbolic vocabulary. The five also demonstrates how powerful messing with that vocabulary can be. The effect is kind of breathtaking, yes? Certainly it helps to elicit a visceral feeling of the work memorials and monuments do.

FIGURE 2 Strom Thurmond Memorial

A few basic principles, to build on this feeling, will make understanding memorials and monuments easy. First, they are powerful. Second, they are doing their best work when they seem to fit seamlessly into the landscape; when they stop being noticeable, their job is done. Third, they are more about the time they are made than the time they memorialize. Fourth, they are made by peoplewho feel strongly that they have something very important to say. Fifth, they are not neutral. Ever. Sixth, they dont innocently remember a discrete event; they invent a particular past that they worry will not be recognized without a memorial. Seventh, they are often inspired by anxiety, not the confidence the bronze and limestone might seem to project; they come from an unsettled moment. And, eighth, memorials use a few basic and familiar conventions to make their points.

FIGURE 3 Strom Thurmond detail

Each of these principles deserves a little fleshing out.

First, they are powerful. This may seem obvious, but it is not necessarily always explicit. They are built to convey power: the power of a particular group in a particular time and place. They claim shared public space with authority, and they claim their ideas for all who share that public spaceor who aspire to. In the case of the Thurmond memorial, which was built after his death in 2013, he stands in broad daylight representing the ideas he stood for across his political career: an explicit, repeated, unrepentant insistence on white supremacy. And here, this term is used in its simplest form; it is neither hyperbolic nor a reference to racist white fraternal organizations. Thurmond fought for segregation and repeatedly expressed his belief in the need to protect white spaces from Black people. So, that is what he claims as he stands on the lawn of the capitol in Columbia in 2021. He doesnt need to wear a Klan robe or be shown enacting violence to express the ongoing power of his ideas in South Carolina. In a state with a population of nearly 1.5 million African Americans, a celebration of a figure with his ideas is a blunt expression of power. (There are also many college and university buildings named for him in the state, as well as high schoolsand even a lake.)

Thus, to say that memorials are powerful is to say two things: (1) that they convey power, and (2) that they are effectivethey really matter. A useful shorthand for this is the specter of protesters pulling down monuments and protesters fighting to protect them. (Think Charlottesville in May 2017.)

Second, they are doing their best work when they seem to fit seamlessly into the landscape; when they stop being noticeable, their job is done. Or maybe it is more accurate to say that when they stop being noticeable, they maintain the power they express. In other words, they never stop working, but the less noticeable they are, the more effectively they have conveyed their message. For example, the memorial in a small town to soldiers killed in the First World War is likely to be a figure of a doughboy, a soldier on a plinth, in a public place. Standing there, season after season, the soldier probably does not figure explicitly in the thinking of teenagers who gather in the park to smoke and drink. They are not likely to think about it much at all, except maybe as a place to duck various authorities. But it is still doing its work, sending the message that they could be called up, could be asked to fight and die, and the world would keep spinningthe town would return to business as usual. It conveys that military sacrifice is such a fundamental part of the culture that it doesnt need to be made explicit.