For Susan

Published by Otago University Press

Te Whare T o Te Wnanga o tkou

533 Castle Street

Dunedin, New Zealand

www.otago.ac.nz/press

First published 2020

Copyright Ken Gorbey

The moral rights of the author have been asserted.

ISBN 978-1-98-859237-4 (print)

ISBN 978-1-98-859295-4 (EPUB)

ISBN 978-1-98-859296-1 (Kindle mobi)

ISBN 978-1-98-859297-8 (ePDF)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of New Zealand. This book is copyright. Except for the purpose of fair review, no part may be stored or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including recording or storage in any information retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. No reproduction may be made, whether by photocopying or by any other means, unless a licence has been obtained from the publisher.

Editor: Anna Rogers

Index: Lee Slater

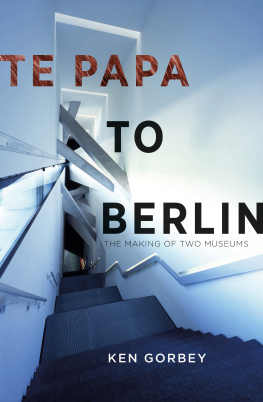

Cover: Main staircase, Jewish Museum Berlin. Photo Jens Ziehe, Jewish Museum Berlin.

Ebook conversion 2021 by meBooks

CONTENTS

WHEN, IN 1997 , I accepted the German governments invitation to become the chief executive of a planned Jewish museum in Berlin, I had only a hazy idea of what awaited me. I understood that the project was deeply enmeshed in national politics, and for that I came with a certain amount of experience from my days in Washington. I had also just written a book on German-Jewish history. However, I was not fitted for the task of defining a viable concept and actually translating it into the creation of a living museum suitable for viewing by a broad national and international audience.

From the beginning, therefore, I was aware of the critical need to find a partner who would help guide the effort, someone with real museum experience and a proven record of accomplishment in the field. Finding the right one would be the key to the success or failure of the entire project.

To create a Jewish museum in the capital city of the recently reunited Federal Republic of Germany would surely be no ordinary undertaking. Given the terrible twentieth-century history of German-speaking Jewry, there were deep emotions and sensitivities on all sides. So what sort of museum would be appropriate and do justice to the ups and downs of Jewish history in Germany and its disastrous end under German Nazism? Should it deal primarily with the Holocaust? Should it focus on the longer history, on art or on the contributions of prior generations of German-Jewish citizens to national life? The Nazis had destroyed not only Jewish life in Germany, but also its symbols and artefacts, so what was there to exhibit? And how would any of it fit into the dramatic architecture of the building which the government had commissioned Daniel Libeskind to design for the purpose?

To get some clarity about these and related questions, I sought the opinion of a broad cross-section of scholars, historians and museum executives, whose advice proved to be highly diverse and, more often than not, maddeningly contradictory. Some even suggested that the whole idea of a Jewish museum in the land of the Holocaust perpetrators was a profoundly bad idea and should be abandoned.

Eventually one idea evolved that appealed to me. Jews had lived continuously on German soil since the Roman period. There had been good times for them when they lived in relative peace and harmony with their neighbours, and others when they were isolated, persecuted and harassed. Over the centuries, they had become deeply enmeshed in, and made major contributions to, every aspect of German life, eventually as full citizens with equal rights. All this had come to a bloody end under the Nazis. Hence, the idea was to create a storytelling museum and this 2000-year history of the Jewish presence in Germany with all its ups and downs would be the story that the Jewish Museum Berlin (JMB) would tell.

But who could help me do it? Ideally it would have to be someone with deep knowledge of German-Jewish history and culture, and probably a Jew. He or she would have broad experience as a proven museum leader and manager able to function effectively in a German environment, preferably a German speaker. (The JMB was to be bilingual in German and English.) Furthermore, it would have to be someone with the imagination and skill to fit all this storytelling into the brilliant, evocative, but complex and intricate architecture Libeskind had designed.

This was a formidable combination of qualifications indeed, and very hard to find. Initially I had despaired of coming up with a suitable candidate. But then, in a near miracle, I got lucky.

When Shaike Weinberg, a brilliant museum expert, creator of the famous Tel Aviv storytelling museum of the Jewish diaspora and a leader of Washingtons Holocaust Memorial Museum, agreed to join me, it seemed that my prayers had been answered. Shaike had virtually all of the qualifications needed and as he set about guiding the complicated task of translating our concept into reality, I thought I saw the light at the end of the tunnel. We were on our way, and I could not have been happier. But disaster struck less than a year later when Shaike fell seriously ill and died soon thereafter. We had become good friends and I mourned and missed him greatly. And once again I was confronted with the problem of finding someone with the right qualifications to continue the work he had begun.

Museum-makers experienced in strong storytelling museums are exceedingly rare because very few museums of this type exist. One of the best, I was told, was a wildly successful one in, of all places, faraway New Zealand. Te Papa, the countrys national museum in Wellington, was said to be an extraordinary place that had attracted an unheard-of throng of visitors far beyond anyones expectation. Its creator, a fellow named Ken Gorbey, was the kind of imaginative museum leader with deeply relevant experience I should be looking for.

I can no longer remember what possessed me to seriously consider actually reaching out to this fabled Kiwi as a possible answer to my increasingly serious dilemma. The Jewish Museum Berlin was under pressure to open within the impossibly short time of two years and I had no one to help make it happen. I therefore decided in desperation, to be honest to consider him more closely.

Yet to give serious consideration to someone who did not know Germany, or German-Jewish history, was not Jewish, spoke not a word of German and, as far as anyone knew, had never worked far away from his down-under home seemed more than a little preposterous. And yet he was the creator of a highly successful museum of the type I wanted for Berlin. So without an alternative or a better idea, I decided to give this impossible idea a try.

I had my doubts, but when Ken agreed to come to Berlin for a talk, we clicked almost immediately. Offering him the job was, I realised, one of the riskiest gambles in a lifetime of management assignments with the responsibility to attract top-notch executive personnel. And when Ken actually agreed, I spent more than one sleepless night worrying about what I had done and how it would all work out. In Berlin, the scepticism, if not dismay, among my as yet small cadre of colleagues was also enormous. How could it possibly work, they argued, to bring in this man from faraway New Zealand, and expect that he could successfully work his magic in Germany with a Jewish museum, on a subject matter with which he was totally unfamiliar?

Next page