Publication of this book was made possible in part by a generous donation from the Presidents Office of the University of Texas at Austin.

The University Press of Mississippi is the scholarly publishing agency of the Mississippi Institutions of Higher Learning: Alcorn State University, Delta State University, Jackson State University, Mississippi State University, Mississippi University for Women, Mississippi Valley State University, University of Mississippi, and University of Southern Mississippi.

www.upress.state.ms.us

The University Press of Mississippi is a member of the Association of University Presses.

Copyright 2019 by University Press of Mississippi

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

First printing 2019

All photographs were taken by the author unless otherwise indicated.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Woodard, Helena, 1953 author.

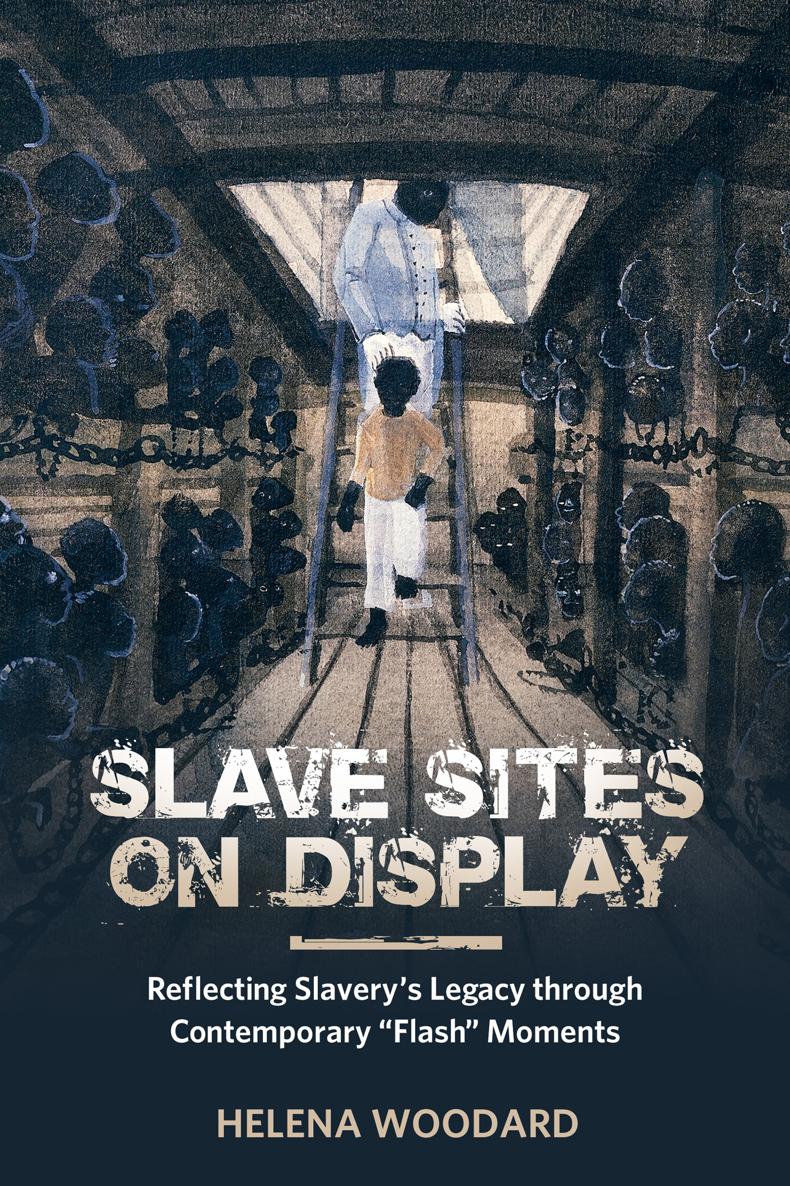

Title: Slave sites on display : reflecting slaverys legacy through contemporary flash moments / Helena Woodard.

Description: Jackson : University Press of Mississippi, [2019] | Series: African diaspora material culture series | First printing 2019. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019006709 (print) | LCCN 2019022332 (ebook) | ISBN 9781496824165 (hardcover : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781496824172 (pbk. : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: SlaveryUnited StatesHistory. | African diaspora.

Classification: LCC E441 .W874 2019 (print) | LCC E441 (ebook) | DDC 306.3/620973dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019006709

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019022332

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data available

INTRODUCTION

The temporal status of any act of memory is always the present and not, as some nave epistemology might have it, the past itself, even though all memory in some ineradicable sense is dependent on some past event or experience.

Andreas Huyssen, Twilight Memories

Like the dead-seeming, cold rocks, I have memories within that came out of the material that went to make me. Time and place have had their say.

Zora Neale Hurston, Dust Tracks on a Road

Rather than invent a world, I want a different means to understand this one.

Jena Osman, The Network

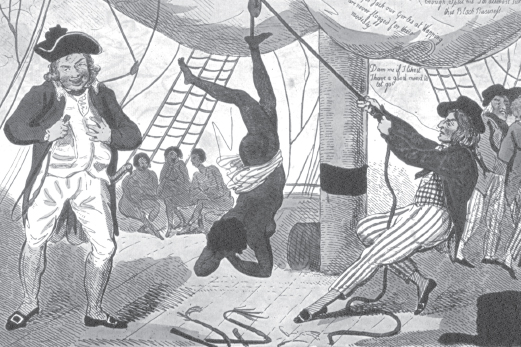

At a slavery exhibit, And Still We Rise, at Detroits Charles Wright Museum, a horrific image greets the visitor. The illustrator, Isaac Cruikshank, in a replica of the eighteenth-century sketch titled The Abolition of the Slave Trade, depicts a young African girl suspended upside down on a slave ship while the captain brandishes a whip nearby. On display is a whip in a glass frame, flanked by a narrative panel that reads: Captain John Kimber fell afoul of the law in 1792. He was accused of whipping an enslaved African girl to death because she refused to dance naked on the deck of the slave ship. He was arrested, tried, and acquitted by a jury that said the girl died of disease. In April 1792, implying the girls alleged pregnancy and her right to protect her modesty, abolitionist William Wilberforce delivered a speech about the episode before the House of Commons as part of an effort to end the slave trade. Following Wilberforces speech, Isaac Cruikshank created the illustration, which further sensationalized the incident.

At Englands Birmingham Museum, in a special temporary exhibit in 2007 that honored author and former slave Olaudah Equiano and also commemorated the two hundredth anniversary of the ending of the slave trade, a film short also featured the Cruikshank sketch. Dance Is Us and Dance Is Black, produced by British choreographer Rodrequez King-Dorset, shows an animated reenactment of the girls beating, complete with sounds of a cracking

As the museum exhibits at Detroit and Birmingham demonstrate, the enslaved girls murder, which caused a sensation in England in 1792 and inspired the famous sketch, has regained currency more than two centuries after the incident occurred. (Indeed, images of the Cruikshank sketch exist at other museum exhibitions in the United States and in the United Kingdom.) But while the Detroit exhibit replicates the incident as yet another atrocity committed upon the body of an unidentified slave, the Birmingham exhibit disrupts time and space, and imagines the girls autonomy to command her own performance. Rather than stage the dance as a compulsory, demeaning mode of entertainment for the slave ships captain and crew, the choreographer offers it as a communicative cultural expression through narration and performance for the modern-day spectator.

That the exhibit at Birmingham conflates aesthetic forms long established in black expressive discourse is not a novel convention. Through a creative exhibition aided by modern technology, the choreographer transforms the enslaved girls fate from a life brutally cut short in the eighteenth century to one that freedom and progress make possible in the twenty-first century. In so doing, the exhibition does not just transform a past traumatic event from official archival records into a revisionist reproduction or reconstructed material. It also radically alters the ways in which the event is remembered, as well as the manner in which the enslaved subject is depicted. That disconnect between archiving the slave past and altering the ways in which it is remembered and/or rewritten for public consumption in the present day is the primary focus of my study.

Through historical intervention, Rodrequez King-Dorsets Dance Is Us and Dance Is Black counters the demeaning, brutal dance of death on the deck of a slave ship by staging a dance of deliverance for an unnamed slave girl who will forever remain unknowable. The exhibition therefore poses as both rehabilitative art for her fate and critical engagement with colossal failures in the archival record. But it also typifies limitations of a recuperative agenda that seeks to repair or otherwise restore a disembodied slave subject in futurity. Even at trial in the eighteenth century, slavery advocates characterized the young slave girl as a prostitute, while abolitionists designated her as a

In this study of the seemingly intractable problem described above, I find a growing number of modern-day slave sites and revisionist exhibitions in the global community particularly instructive and relatable, but only when grounded in a specific, contemporary cultural and social milieu or geopolitical framework, such as community, environment, and racial ideology, contiguous with the slave past. Consequently, I am especially interested in how select modern-day slave sites and exhibitionsincluding the renovated slave fort, slave burial ground, reconstructed slave ship, and Bench by the Road slave memorial at Sullivans Islandrespond to the political economy of the conditions in which they are displayed. Each of the sites that I examine in this study accesses a distinct historical dimension, such as the slaves imprisonment and deportation from an African homeland, the Middle Passage journey across the Atlantic, and burial in unmarked graves. In addition, each tells a story about the slave past, relative to the lived experiences of the disproportionately diaspora slave descendants that organize and visit these sites. Though they differ from one another, all of these sites are displayed as slave memorials or monuments that function as high-profile tourist attractions, structured mostly in outdoor settings as either fixed or movable objects, as opposed to displays inside a traditional museum edifice.