DENMARK VESEYS REVOLT

AMERICAN ABOLITIONISM AND ANTISLAVERY

John David Smith, series editor

THE IMPERFECT REVOLUTION:

ANTHONY BURNS AND THE LANDSCAPE

OF RACE IN ANTEBELLUM AMERICA

Gordon S. Barker

A SELF-EVIDENT LIE:

SOUTHERN SLAVERY AND THE THREAT

TO AMERICAN FREEDOM

Jeremy J. Tewell

DENMARK VESEYS REVOLT:

THE SLAVE PLOT THAT LIT A FUSE

TO FORT SUMTER

John Lofton

New Introduction by Peter Charles Hoffer

Denmark Veseys

Revolt

The Slave Plot That Lit a Fuse to Fort Sumter

JOHN LOFTON

New Introduction

by Peter Charles Hoffer

THE KENT STATE UNIVERSITY PRESS

Kent, Ohio

Copyright 1964, 1983, 2013 by John Lofton

New Introduction 2013 by The Kent State University Press, Kent Ohio 44242

All rights reserved

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 2013012600

ISBN 978-1-60635-171-0

Manufactured in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Lofton, John.

[Insurrection in South Carolina]

Denmark Veseys revolt : the slave plot that lit a fuse to Fort Sumter / John Lofton ; new introduction by Peter Charles Hoffer.

pages cm. (American abolitionism and antislavery)

Originally published under title: Insurrection in South Carolina. Yellow Springs, Ohio : Antioch Press, 1964.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-60635-171-0 (pbk.)

1. Charleston (S.C.)HistorySlave Insurrection, 1822.

2. Vesey, Denmark, approximately 17671822. 3. SlaverySouth Carolina.

I. Title.

F279.C49N44 2013

306.36209757dc23

2013012600

17 16 15 14 13 5 4 3 2 1

NEW INTRODUCTION

THE RETURN OF DENMARK VESEY

The Civil Rights movement spurred a revolution in the writing of American history, particularly on the history of blacks in the South. To be sure, there were precedents. W. E. B. DuBois was a historian as well as a sociologist, and his 1915 The Negro was a work of scholarship as well as advocacy for African Americans rights. Carter G. Woodson earned a Ph.D. in history from Harvard in 1912 and was the founding editor of the Journal of Negro History in 1916 and a decade later introduced Negro History Week (expanded to Black History Month in 1976). John Hope Franklin, born the year that The Negro was published, began his storied career in the 1940s with the publication of The Free Negro in North Carolina, 17801860 (1943). But the 1960s saw the beginning of a surge of young black men and women entering the historical profession. With them came the publication of a history in which people of color were not only victims but agents and heroes of their own stories. Men of color who as late as the 1930s were dismissed as ignorant or bestial in racist historical accounts were restored to their rightful place as spokesmen for an oppressed people.1

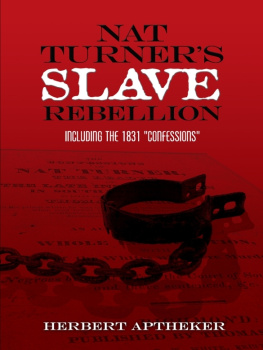

Nothing so oppressed people of color in America as chattel slavery. In the 1950s, a new generation of scholars, led by Franklin and Kenneth M. Stampp, denounced the moon and magnolias school of slave histories for what they were, a myth, and reminded readers of the harshness of slavery. In the 1970s, black scholars like John W. Blassingame joined white scholars like Eugene D. Genovese to recreate the cultural world the slaves made. They explored the many ways in which slaves resisted their bondage. Earlier studies such as Herbert Apthekers 1939 classic account of American slave revolts were reprinted and taken seriously.2

In this peculiar institution men and women were regarded by law as pieces of personal property, with no rights as people, none, according to one Chief Justice of the United States, which the white man was bound to respect. Slave codes based on English West Indian colonial law denied slaves any semblance of legal personhood. They could be sold, given away, inherited, used to pay debts, rented out or leased, and moved about like any other pieces of personal property. They could not sue, serve on juries, make contracts, own, acquire or dispose of property of their own, legally marry, raise their children, and in some states learn to read or write. They could not carry firearms, travel, nor congregate without passes from their masters or under white supervision. Masters who wanted to free slaves had to remove them from the slave states.

Not all of these laws were enforced to the letter, for the slavery system was above all a labor system, and the slaves labor could only be fully exploited if slaves were allowed to hunt, fish, cultivate their own gardens, go to market, sell their own crafts, and otherwise participate in commercial activities for their own benefitat least according to law. In the case of South Carolina, such contradictions twisted the laws every which way. For much of its colonial existence, and the better part of the antebellum period, South Carolina had a black majority, and its laws, modeled on those of the British Sugar Islands in the Caribbean, were harsh. But when some South Carolina legislators wanted to mandate the execution of runaway slaves, the majority of the Commons House demurred. Was that because a runaway was still a valuable piece of property, or because masters and slaves knew that many runaways simply ran from a cruel new owner back to a decent former master? Why require that slave fishermen pay for a license when slaves were not allowed to own boats? Was it because slave fishermen were very able, and fish plentiful in the creeks, rivers, and along the ocean shore? The Assemblymen refused to deny to slaves the practice of going to market for their masters, whatever liberties this allowed the slave to trade on the side for himself.3

Indeed, no state was more wedded to the institution of slavery than South Carolina. Its rice and later cotton crops were great prizes in the Atlantic market, but without slaves, Carolinas coastal wetlands would never have been profitable enough to merit cultivation. With slaves, no planter ever rested wholly secure in his bed. South Carolina slavery has drawn to itself some of the finest studies of slavery in the postCivil Rights era: Peter H. Woods pathbreaking study of African influences on low country slavery; Peter A. Coclaniss lyrical reimagining of life on the rice plantations; Robert Olwells insightful analysis of the political ideology of slavery and mastery; Philip H. Morgans comprehensive comparison of rice country slavery with slavery in the Chesapeake; S. Max Edelsons study of the economics of the slave plantation; and J. William Harriss poignant tale of a free black ship captain executed on the eve of the American Revolutiondespite the intercession of the royal governor.4

Slaves were present in all of the British North American colonial cities, and although state gradual emancipation laws ended slavery in Boston, Newport, New York City, and Philadelphia, slaves abounded in the southern cities of the early republic, especially port cities like Baltimore, Norfolk, Savannah, Mobile, and New Orleans. No city had more slaves per capita, and no slaves were more visible than those of antebellum Charleston. They outnumbered whites by 63,615 to 18,768 in the Charleston district in 1800. There were slightly fewer than six hundred free blacks in the city at that time. Freedom for these men and women came with stringstheir children were still slaves, as were there spouses in many cases.