American Uprising

The Untold Story of

Americas Largest Slave Revolt

Daniel Rasmussen

Contents

THOUGH THE CAUSE OF EVIL PROSPER, YET TIS TRUTH ALONE IS STRONG.

James Russell Lowell

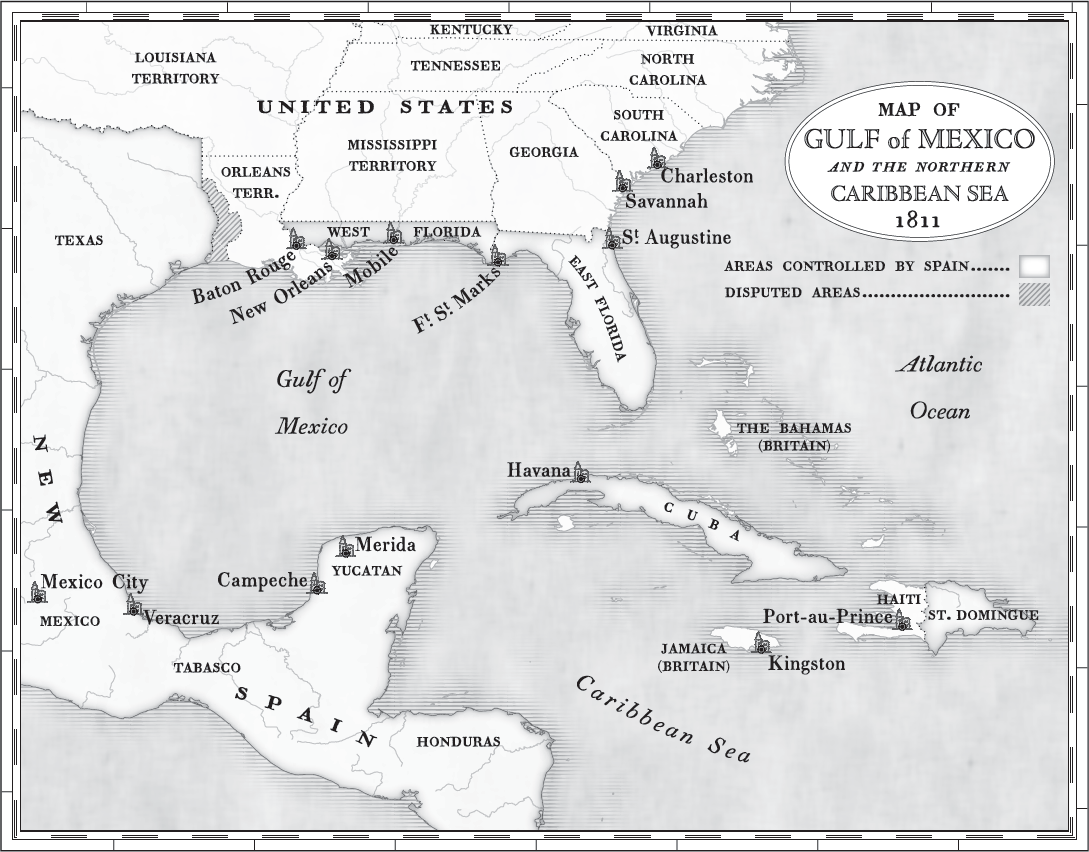

I n 1811, a group of between 200 and 500 enslaved men dressed in military uniforms and armed with guns, cane knives, and axes rose up from the slave plantations around New Orleans and set out to conquer the city. They decided that they would die before they would work another day of backbreaking labor in the hot Louisiana sun. Ethnically diverse, politically astute, and highly organized, this slave army challenged not only the economic system of plantation agriculture but also the expansion of American authority in the Southwest. Their January march represented the largest act of armed resistance against slavery in the history of the United Statesand one of the defining moments in the history of New Orleans and, indeed, the nation.

In the cane fields outside of the city, federal troops teamed up with French planters to fight these slave-rebelsan unholy alliance between government power and slave-based agriculture that would come to define the young American nation as a slave country in the years leading up to the Civil War. Over the course of the conflict, these powerful white men committed unspeakable acts of brutality in service of a stronger nation and a more vibrant economy.

Because of that brutality, and because of a shared belief in the importance of a specific form of political and economic development, these government officials and slave owners sought to write this massive uprising out of the history booksto dismiss the bold actions of the slave army as irrelevant and trivial. They succeeded. And in doing so, they laid the groundwork for one of the most remarkable moments of historical amnesia in our national memory.

While Nat Turner and John Brown have become household names, Kook and Quamana, Harry Kenner, and Charles Deslondes have barely earned a footnote in American history. Though the 1811 uprising was the largest slave revolt in American history, the longest published scholarly account runs a mere twenty-four pages.

This book redresses that silence and tells the story that the planters could not and would not tellthe story of political activity among the enslaved. What follows is the first definitive account of this central moment in our nations pasta story more Braveheart than Beloved : an account of the planning, execution, and suppression of a furious uprising, set in a plantation world far removed from the Virginia of Nat Turner or the sun-drenched plantations of Gone with the Wind. This is a story about slave revolutionaries: their lives, their politics, and their fight to the death against the planters and their militia. Above all, this is a story about America: who we are, where we came from, and how our ideals have at times been twisted and cast aside for the sake of greed and power.

Chapter One

Carnival in New Orleans

THE RIVER LEFT GOLD IN THE DELTA. IT WAS GOLD THE COLOR CHOCOLATE, GOLD THAT WAS NOT IN THE EARTH BUT WAS THE EARTH... TO TAKE LAND FROM THE RIVER, TO CLEAR IT, DRAIN IT, AND PROTECT IT, REQUIRED AN ENORMOUS OUTLAY OF CAPITAL AND LABOR. FROM THE FIRST THE DELTA DEMANDED ORGANIZATION, CAPITAL, ENTREPRENEURSHIP, AND GAMBLING INSTINCTS. IT WAS A PLACE FOR EMPIRE.

John M. Barry, Rising Tide

D own from the mountains of Canada, through dozens of tributaries and smaller rivers, the waters of the American Midwest find their outlet to the sea in the great American Nile: the Mississippi. The river snakes seaward, building tremendous momentum as it hurtles around sharp curves and lashes over rocks, constantly colliding against its own wide banks. For the last 450 miles before the river reaches the ocean, the river bed lies below sea level, and the water has no reason to flow. The water simply tumbles over itself, spitting and gurgling past Natchez and down to New Orleans.

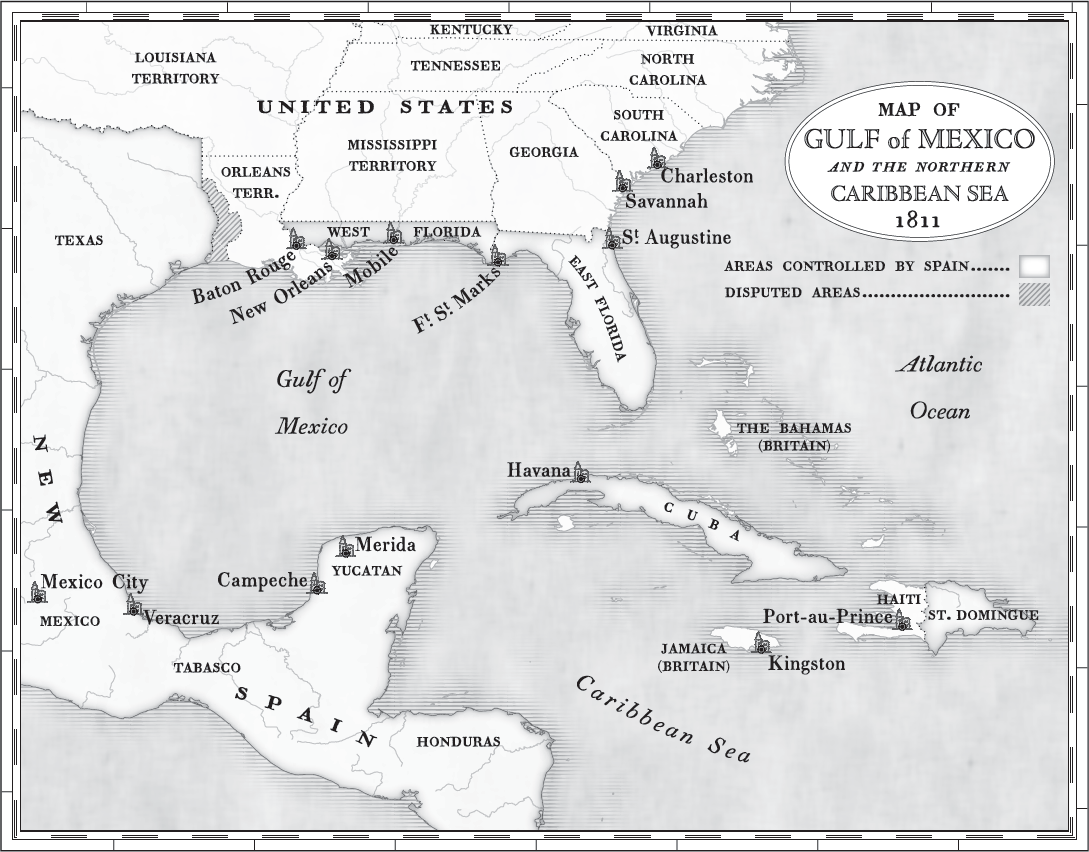

From New Orleans, the river flushes out into the Gulf of Mexico, carrying the continents commerce into an ocean world rich with portsfrom the coast of Africa to the Caribbean to the eastern seaboard of the United States. Situated at the mouth of the river, New Orleans is the prime entrepot of the American Midwest. In the nineteenth century, the city was of central strategic and commercial significance, for through the city, as Thomas Jefferson noted, the produce of three-eighths of our territory must pass to market. New Orleans was the point at which the commercial farming zones of the Mississippi River valley met the world of Atlantic trade.

Just a few miles north and west of the city, only a few miles up the Mississippi River, began one of the wealthiest and most fertile stretches of agricultural land in North America: Louisianas famed German Coast. Germans had originally settled the area before being overwhelmed by French immigrants and, in many cases, frenchifying their names and their culture in order to fit in with the new dominant group. Past the gentle slope of the levee stretched green fields as far as the eye could see on both shores. Magnolias, orange trees, and thick oaks sprouted from the sweeping lawns, and Spanish moss hung from the branches. Shielded behind the lush proliferation of gardens stood gorgeous plantation homes built in colonial style, with soaring roofs and columned porticoes.

About twenty miles from New Orleans, smack-dab in the center of the German Coast, stood the Red Church, a barnlike building with long glass windows, surrounded by a fenced-in cemetery and presbytery. The aristocratic first families of Louisiana streamed out from the front doors.

It was Epiphany Sunday, January 6, 1811, and the planters and their families were buoyant with excitement, undampened by any undue religious solemnity. The local priest was not known for conducting a particularly spiritual Mass. The social status of the parish priests at the time was not very respectable, wrote one French official. Adventurers, gluttons, drunkards, often unfrocked monks, they were asked but one thing by their parishionersthat they be, as was said, good natured.

Good nature was inescapable that Sunday. The previous years sugar crop was in, and the planters had much to look forward to. Epiphany marked the beginning of a month-long Carnival season. Until its ritual ending at Mardi Gras, all-night parties, mixed-race balls, and constant gambling would occupy the planters lives. The local French newspaper LAmi des Lois noted plans for an opera and ball at the end of January, and advertised the services of a French-trained dancing master from Haiti and a Parisian hairdresser eager to help the planters and their wives survive the hectic social calendar. Conversations abounded with joy and optimism as the citizens celebrated the unprecedented success of the 1810 harvest.

Several planters, dressed in gloves, hats, and cravats, strolled toward the plantation of Jean Nol Destrehan, a slender Frenchman with dark hair and brown eyes. The roads bustled with carriages and horses; men and women strolled along the levee in their Sunday finery; and slaves hunted and played games in the fields. The planters had a busy day ahead of them. Destrehan, whom one contemporary described as the most active and intelligent sugar planter in the country, would host lunch at his mansion.