Table of Contents

Guide

ALSO BY ETHAN J. KYTLE

Romantic Reformers and the Antislavery

Struggle in the Civil War Era

ALSO BY BLAIN ROBERTS

Pageants, Parlors, and Pretty Women:

Race and Beauty in the Twentieth-Century South

2018 by Ethan J. Kytle and Blain Roberts

Portions of the following article are reprinted with the permission of the Journal of Southern History: Blain Roberts and Ethan J. Kytle, Looking the Thing in the Face: Slavery, Race, and the Commemorative Landscape in Charleston, South Carolina, 18652010, Journal of Southern History 78 (August 2012): 639684.

Portions of the following chapter are reprinted with the permission of the University Press of Florida: Ethan J. Kytle and Blain Roberts, Is It Okay to Talk about Slaves? Segregating the Past in Historic Charleston, in Destination Dixie: Tourism in Southern History, ed. Karen L. Cox (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2012), 137159.

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced, in any form, without written permission from the publisher.

Requests for permission to reproduce se lections from this book should be mailed to: Permissions Department, The New Press, 120 Wall Street, 31st floor, New York, NY 10005.

Published in the United States by The New Press, New York, 2018

Distributed by Two Rivers Distribution

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Names: Kytle, Ethan J., author. | Roberts, Blain, author.

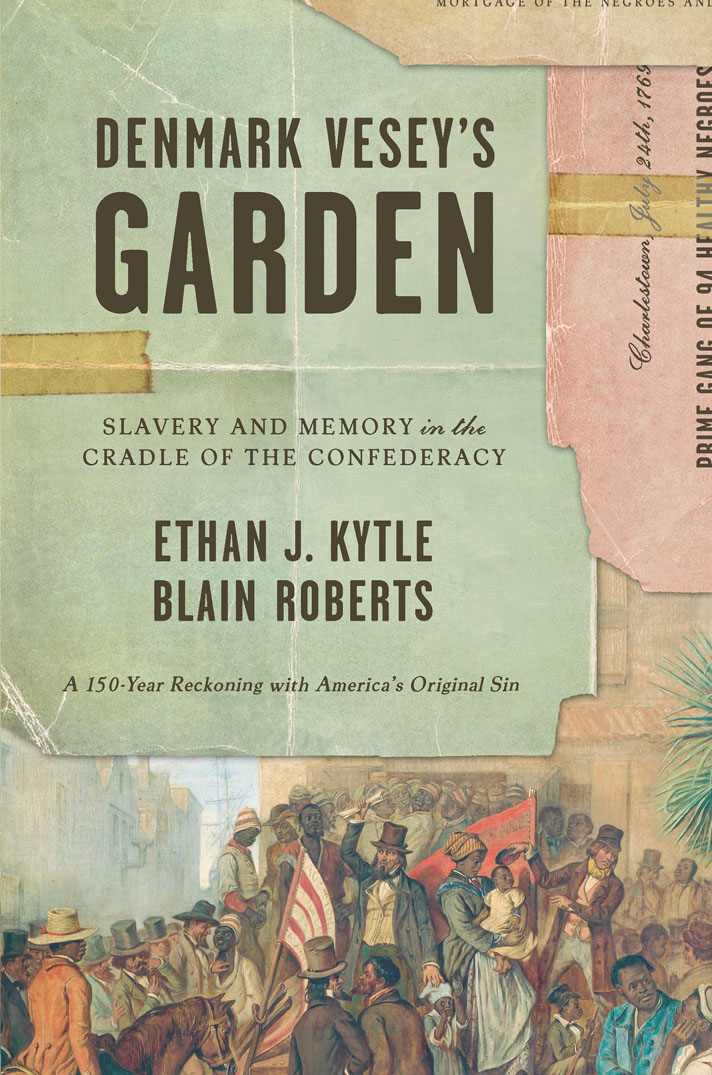

Title: Denmark Veseys garden: slavery and memory in the cradle of the Confederacy / Ethan J. Kytle and Blain Roberts.

Description: New York; London: The New Press, [2018] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017041546 | ISBN 9781620973660 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: SlaverySouth CarolinaCharlestonHistory. | MemorySocial aspectsSouth CarolinaCharleston. | Vesey, Denmark, approximately 1767-1822. | Charleston (S.C.)HistorySlave Insurrection, 1822. | Emanuel AME Church (Charleston, S.C.)

Classification: LCC F279.C457 K97 2018 | DDC 975.7/91503092dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017041546

The New Press publishes books that promote and enrich public discussion and understanding of the issues vital to our democracy and to a more equitable world. These books are made possible by the enthusiasm of our readers; the support of a committed group of donors, large and small; the collaboration of our many partners in the in de pen dent media and the not-for-profit sector; booksellers, who often hand-sell New Press books; librarians; and above all by our authors.

www.thenewpress.com

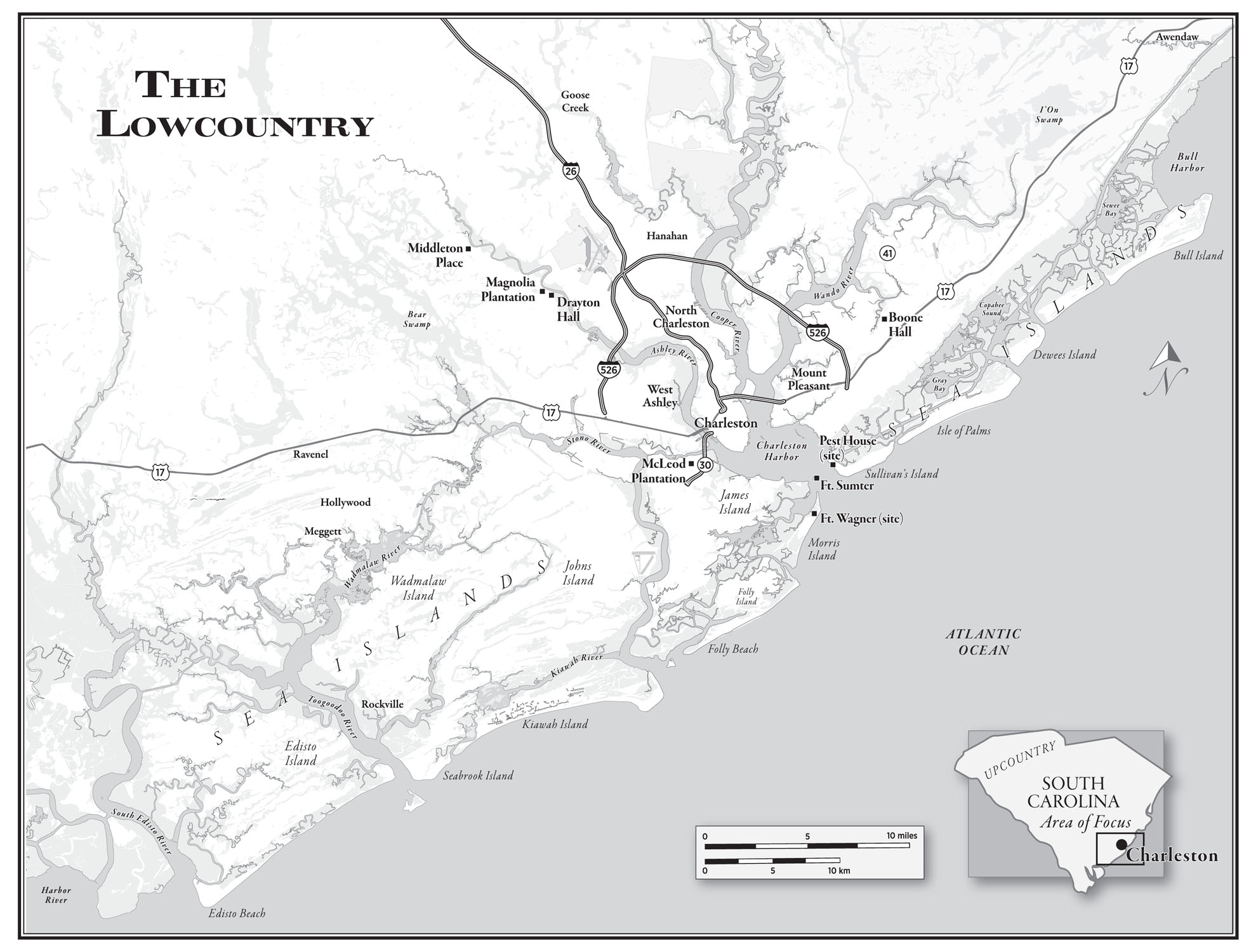

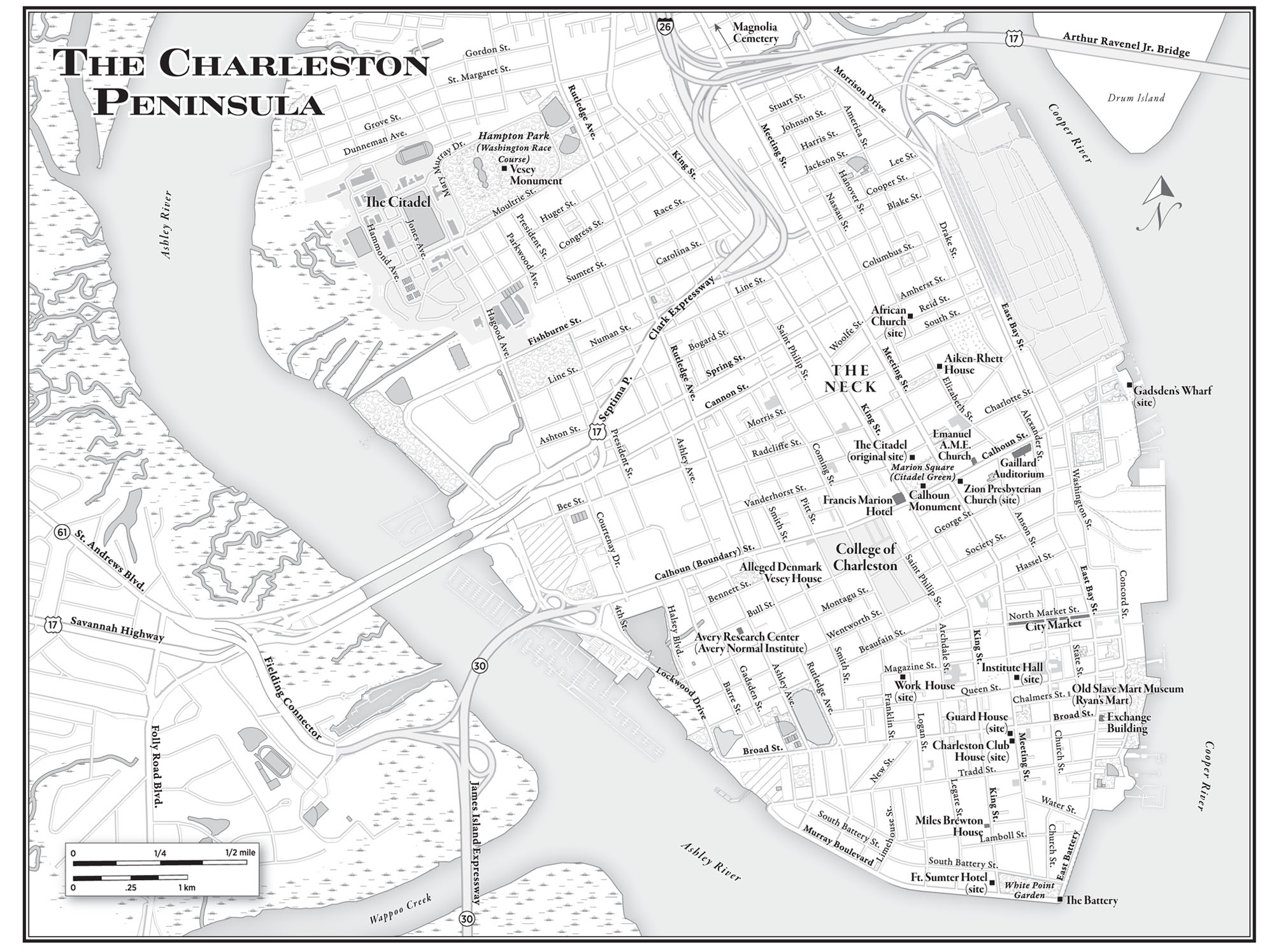

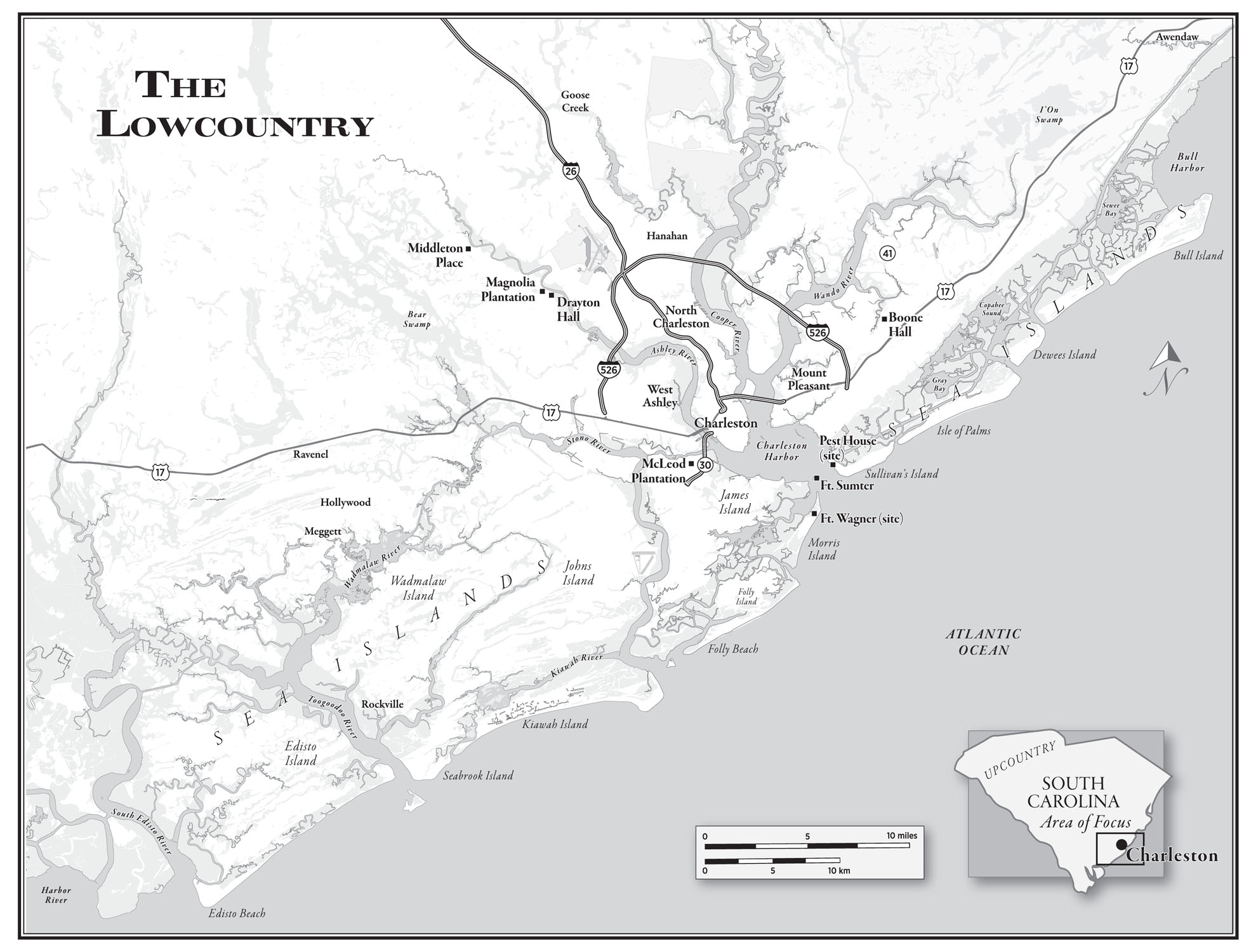

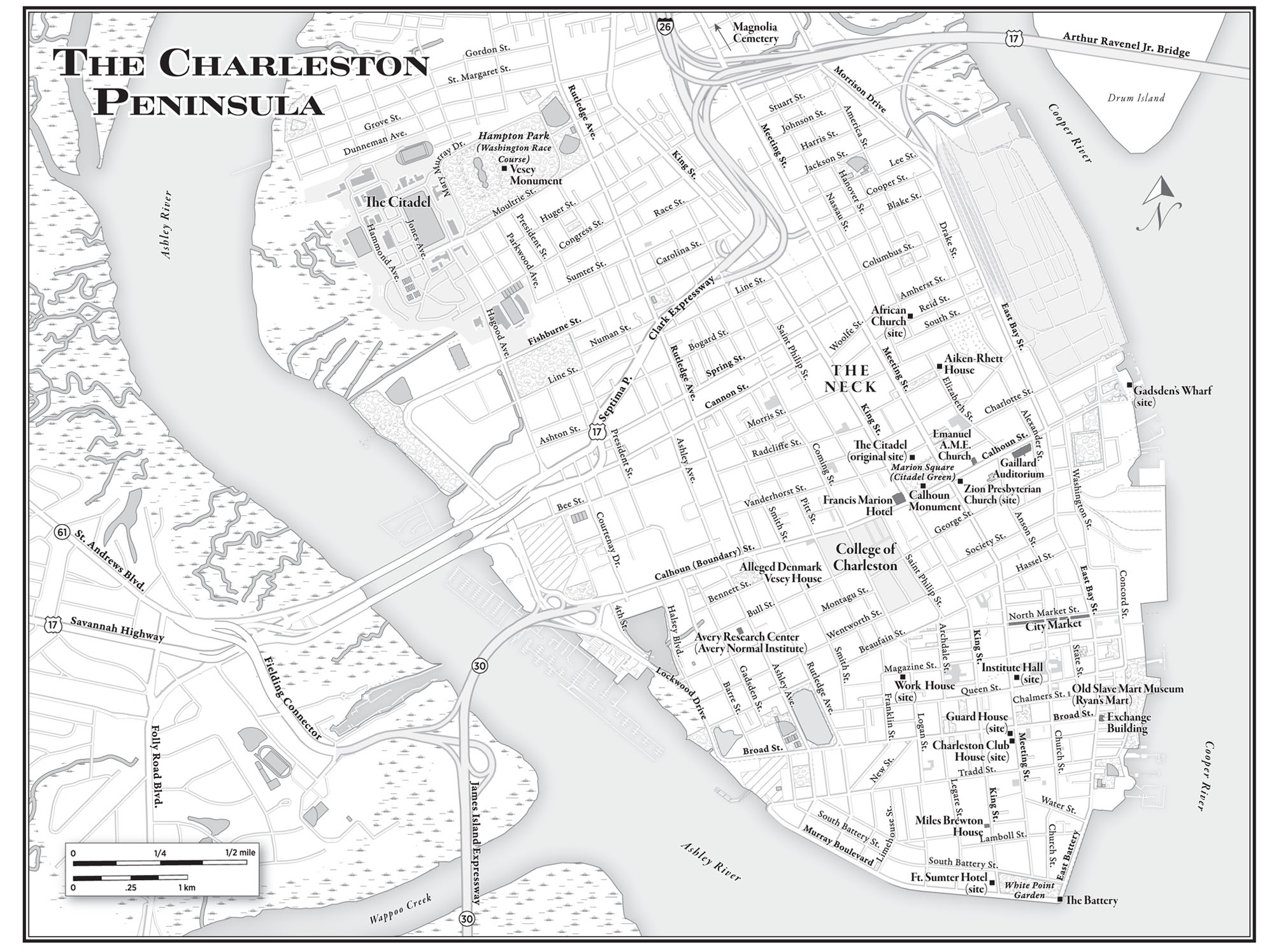

Cartography by Nick Trotter

Book design by Lovedog Studio

Composition by Westchester Publishing Services

This book was set in Garamond Premier Pro and Craw Modern

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Eloise and Hazel

Here [in Charleston] is a subtle flavor of Old World things, a little hush in the whirl of American doing. Between her guardian rivers and looking across the sea toward Africa sits this little Old Lady (her cheek teasingly tinged to every tantalizing shade of the darker blood) with her shoulder ever toward the street and her little laced and rusty fan beside her cheek, while long verandas of her soul stretch down the backyard into slavery.

W.E.B. DU BOIS, 1917

Contents

ON A SWELTERING JUNE EVENING IN 2015, MEMBERS OF Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina, welcomed a stranger into their weekly Bible study group. For this gesture of Christian fellowship, most of them received a death sentence. After listening quietly for about forty minutes, the visitorDylann Roof, a twenty-one-year-old white supremacist who had driven in from nearby Columbiaopened fire inside the venerable black church, killing nine worshippers. Roof then exited through a side door as calmly as he had entered.

Americans soon learned that Roofs flawed understanding of slavery, among other factors, fueled his racial hatred and his attack. In his online manifesto, he claimed that historical lies, exaggerations and myths about how poorly African Americans had been treated under slavery are today being used to justify a black takeover of the United States. Framing himself as a white savior in the tradition of the Ku Klux Klan, he explained during his confession to the FBI that he targeted Charleston because its a historic city, and at one time, it had the highest ratio of black people to white people in the whole country, when we had slavery.

In the months before the murders, Roof had made six trips to Charleston and the surrounding area. He later told authorities, I prepared myself mentally. During each trip, he visited plantations and other locations associated with slavery, including Emanuel A.M.E. Church. Mother Emanuel, as it is affectionately known, is among the oldest black congregations in the South. It was the church of Denmark Vesey, Charlestons most famousand, to some, infamousblack revolutionary. In 1822, Vesey plotted a massive slave uprising for which he and more than thirty co-conspirators were hastily tried and executed. Before Dylann Roof perpetrated his executions two centuries later, he created an archive of his research into Charlestons enslaved past. In Roofs car, investigators found travel brochures and several sheets of paper on which the white supremacist had scrawled the names of black churches, Emanuel A.M.E. among them, as well as the name of Denmark Vesey. On his website, Roof had posted a chilling series of photographs. Some showed him at sites he had toured. Others captured him brandishing the Confederate flag. In all of the images, a menacing Roof stares at the camera, his hatred now all too easy to see.

After the Emanuel massacre, the country looked and felt different. It was as if a veil hiding something disconcertingan affliction we had been doing our best to ignorehad suddenly been lifted. Behind it sat a toxic mix of beliefs and symbols that, endorsed by some and tolerated by many, came under increased scrutiny. Roofs support for slavery and the Confederacy that waged war to protect it raised troubling questions about how the country has remembered and commemorated its past. Was it acceptable, for instance, that Confederate statues and flags still enjoyed a prominent place in American culture?

Critics insisted it was not. By late June 2015, New Orleans mayor Mitch Landrieu had asked the city council to take down several monuments, including those honoring Confederate generals Robert E. Lee and P.G.T. Beauregard and the Confederate president, Jefferson Davis. In Tennessee, a bipartisan coalition of lawmakers called for the removal of a bust of Nathan Bedford Forrest, a Confederate general and Ku Klux Klan leader. Critics achieved a major victory on July 9, when South Carolina legislators agreed to remove the Confederate battle flag that had flown at the state capitol since the early 1960s. The effort to purge the country of Confederate and proslavery symbols quickly spread beyond the South, as companies such as Amazon, eBay, Walmart, and Sears prohibited the sale of Confederate flags and similar merchandise from their stores and websites.