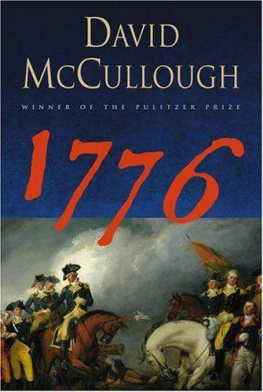

David McCullough - 1776

Here you can read online David McCullough - 1776 full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2005, publisher: Belacqva, genre: History. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:1776

- Author:

- Publisher:Belacqva

- Genre:

- Year:2005

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

1776: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "1776" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

In this masterful book, David McCullough tells the intensely human story of those who marched with General George Washington in the year of the Declaration of Independence -- when the whole American cause was riding on their success, without which all hope for independence would have been dashed and the noble ideals of the Declaration would have amounted to little more than words on paper.

Based on extensive research in both American and British archives, 1776 is a powerful drama written with extraordinary narrative vitality. It is the story of Americans in the ranks, men of every shape, size, and color, farmers, schoolteachers, shoemakers, no-accounts, and mere boys turned soldiers. And it is the story of the Kings men, the British commander, William Howe, and his highly disciplined redcoats who looked on their rebel foes with contempt and fought with a valor too little known.

At the center of the drama, with Washington, are two young American patriots, who, at first, knew no more of war than what they had read in books -- Nathanael Greene, a Quaker who was made a general at thirty-three, and Henry Knox, a twenty-five-year-old bookseller who had the preposterous idea of hauling the guns of Fort Ticonderoga overland to Boston in the dead of winter.

But it is the American commander-in-chief who stands foremost -- Washington, who had never before led an army in battle. Written as a companion work to his celebrated biography of John Adams, David McCulloughs 1776 is another landmark in the literature of American history.

Amazon.com ReviewEsteemed historian David McCullough covers the military side of the momentous year of 1776 with characteristic insight and a gripping narrative, adding new scholarship and a fresh perspective to the beginning of the American Revolution. It was a turbulent and confusing time. As British and American politicians struggled to reach a compromise, events on the ground escalated until war was inevitable. McCullough writes vividly about the dismal conditions that troops on both sides had to endure, including an unusually harsh winter, and the role that luck and the whims of the weather played in helping the colonial forces hold off the worlds greatest army. He also effectively explores the importance of motivation and troop morale--a tie was as good as a win to the Americans, while anything short of overwhelming victory was disheartening to the British, who expected a swift end to the war. The redcoat retreat from Boston, for example, was particularly humiliating for the British, while the minor American victory at Trenton was magnified despite its limited strategic importance.

Some of the strongest passages in 1776 are the revealing and well-rounded portraits of the Georges on both sides of the Atlantic. King George III, so often portrayed as a bumbling, arrogant fool, is given a more thoughtful treatment by McCullough, who shows that the king considered the colonists to be petulant subjects without legitimate grievances--an attitude that led him to underestimate the will and capabilities of the Americans. At times he seems shocked that war was even necessary. The great Washington lives up to his considerable reputation in these pages, and McCullough relies on private correspondence to balance the man and the myth, revealing how deeply concerned Washington was about the Americans chances for victory, despite his public optimism. Perhaps more than any other man, he realized how fortunate they were to merely survive the year, and he willingly lays the responsibility for their good fortune in the hands of God rather than his own. Enthralling and superbly written, 1776 is the work of a master historian. --Shawn Carkonen

The Other 1776

With his riveting, enlightening accounts of subjects from Johnstown Flood to John Adams, David McCullough has become the historian that Americans look to most to tell us our own story. In his Amazon.com interview, McCullough explains why he turned in his new book from the political battles of the Revolution to the battles on the ground, and he marvels at some of his favorite young citizen soldiers who fought alongside the remarkable General Washington.

The Essential David McCullough

John Adams

Truman

Mornings on Horseback

The Path Between the Seas

The Great Bridge

The Johnstown Flood

More Reading on the Revolution

The Great Improvisation by Stacy Schiff

Washingtons Crossing by David Hackett Fischer

His Excellency: George Washington by Joseph J. Ellis

Washingtons General by Terry Golway

Iron Tears by Stanley Weintraub

Victory at Yorktown by Richard M. Ketchum

From Publishers WeeklyStarred Review. Bestselling historian and two-time Pulitzer winner McCullough follows up John Adams by staying with Americas founding, focusing on a year rather than an individual: a momentous 12 months in the fight for independence. How did a group of ragtag farmers defeat the worlds greatest empire? As McCullough vividly shows, they did it with a great deal of suffering, determination, ingenuityand, the author notes, luck.Although brief by McCulloughs standards, this is a narrative tour de force, exhibiting all the hallmarks the author is known for: fascinating subject matter, expert research and detailed, graceful prose. Throughout, McCullough deftly captures both sides of the conflict. The British commander, Lord General Howe, perhaps not fully accepting that the rebellion could succeed, underestimated the Americans ingenuity. In turn, the outclassed Americans used the cover of night, surprise and an abiding hunger for victory to astonishing effect. Henry Knox, for example, trekked 300 miles each way over harsh winter terrain to bring 120,000 pounds of artillery from Fort Ticonderoga to Boston, enabling the Americans, in a stealthy nighttime advance, to seize Dorchester Heights, thus winning the whole city.Luck, McCullough writes, also played into the American causea vicious winter storm, for example, stalled a British counterattack at Boston, and twice Washington staged improbable, daring escapes when the war could have been lost. Similarly, McCullough says, the cruel northeaster in which Washingtons troops famously crossed the Delaware was both a blessing and a curse. McCullough keenly renders the harshness of the elements, the rampant disease and the constant supply shortfalls, from gunpowder to food, that affected morale on both sidesand it certainly didnt help the British that it took six weeks to relay news to and from London. Simply put, this is history writing at its best from one of its top practitioners.

Copyright Reed Business Information, a division of Reed Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

David McCullough: author's other books

Who wrote 1776? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.