The reflection upon my situation and that of this army produces many an uneasy hour when all around me are wrapped in sleep. Few people know the predicament we are in.

Chapter One SovereignDuty

God save Great George our King,

Long live our noble King,

God save the King!

Send him victorious,

Happy and glorious,

Long to reign oer us;

God save the King!

ON THE AFTERNOON of Thursday, October 26, 1775, His Royal Majesty George III, King of England, rode in royal splendor from St. Jamess Palace to the Palace of Westminster, there to address the opening of Parliament on the increasingly distressing issue of war in America.

The day was cool, but clear skies and sunshine, a rarity in London, brightened everything, and the royal cavalcade, spruced and polished, shone to perfection. In an age that had given England such rousing patriotic songs as God Save the King and Rule Britannia, in a nation that adored ritual and gorgeous pageantry, it was a scene hardly to be improved upon.

An estimated 60,000 people had turned out. They lined the whole route through St. Jamess Park. At Westminster people were packed solid, many having stood since morning, hoping for a glimpse of the King or some of the notables of Parliament. So great was the crush that late-comers had difficulty seeing much of anything.

One of the many Americans then in London, a Massachusetts Loyalist named Samuel Curwen, found the mob outside the door to the House of Lords too much to bear and returned to his lodgings. It was his second failed attempt to see the King. The time before, His Majesty had been passing by in a sedan chair near St. Jamess, but reading a newspaper so close to his face that only one hand was showing, the whitest hand my eyes ever beheld with a very large rose diamond ring, Loyalist Curwen recorded.

The Kings procession departed St. Jamess at two oclock, proceeding at walking speed. By tradition, two Horse Grenadiers with swords drawn rode in the lead to clear the way, followed by gleaming coaches filled with nobility, then a clattering of Horse Guards, the Yeomen of the Guard in red and gold livery, and a rank of footmen, also in red and gold. Finally came the King in his colossal golden chariot pulled by eight magnificent cream-colored horses (Hanoverian Creams), a single postilion riding the left lead horse, and six footmen at the side.

No mortal on earth rode in such style as their King, the English knew. Twenty-four feet in length and thirteen feet high, the royal coach weighed nearly four tons, enough to make the ground tremble when under way. George III had had it built years before, insisting that it be superb. Three gilded cherubs on topsymbols of England, Scotland, and Irelandheld high a gilded crown, while over the heavy spoked wheels, front and back, loomed four gilded sea gods, formidable reminders that Britannia ruled the waves. Allegorical scenes on the door panels celebrated the nations heritage, and windows were of sufficient size to provide a full view of the crowned sovereign within.

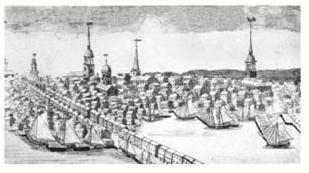

It was as though the very grandeur, wealth, and weight of the British Empire were rolling pastan empire that by now included Canada, that reached from the seaboard of Massachusetts and Virginia to the Mississippi and beyond, from the Caribbean to the shores of Bengal. London, its population at nearly a million souls, was the largest city in Europe and widely considered the capital of the world.

***

GEORGE III had been twenty-two when, in 1760, he succeeded to the throne, and to a remarkable degree he remained a man of simple tastes and few pretensions. He liked plain food and drank but little, and wine only. Defying fashion, he refused to wear a wig. That the palace at St. Jamess had become a bit dowdy bothered him not at all. He rather liked it that way. Socially awkward at Court occasionsmany found him disappointingly dullhe preferred puttering about his farms at Windsor dressed in farmers clothes. And in notable contrast to much of fashionable society and the Court, where mistresses and infidelities were not only an accepted part of life, but often flaunted, the King remained steadfastly faithful to his very plain Queen, the German princess Charlotte Sophia of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, with whom by now he had produced ten children. (Ultimately there would be fifteen.) Gossips claimed Farmer Georges chief pleasures were a leg of mutton and his plain little wife.

But this was hardly fair. Nor was he the unattractive, dim-witted man critics claimed then and afterward. Tall and rather handsome, with clear blue eyes and a generally cheerful expression, George III had a genuine love of music and played both the violin and piano. (His favorite composer was Handel, but he adored also the music of Bach and in 1764 had taken tremendous delight in hearing the boy Mozart perform on the organ.) He loved architecture and did quite beautiful architectural drawings of his own. With a good eye for art, he had begun early to assemble his own collection, which by now included works by the contemporary Italian painter Canaletto, as well as watercolors and drawings by such old masters as Poussin and Raphael. He avidly collected books, to the point where he had assembled one of the finest libraries in the world. He adored clocks, ship models, took great interest in things practical, took great interest in astronomy, and founded the Royal Academy of Arts.

He also had a gift for putting people at their ease. Samuel Johnson, the eras reigning arbiter of all things of the mind, and no easy judge of men, responded warmly to the unaffected good nature of George III. They had met and conversed for the first time when Johnson visited the Kings library, after which Johnson remarked to the librarian, Sir, they may talk of the King as they will, but he is the finest gentleman I have ever seen.

Stories that he had been slow to learn, that by age eleven he still could not read, were unfounded. The strange behaviorthe so-called madness of King George IIIfor which he would be long remembered, did not come until much later, more than twenty years later, and rather than mental illness, it appears to have been porphyria, a hereditary disease not diagnosed until the twentieth century.

Still youthful at thirty-seven, and still hardworking after fifteen years on the throne, he could be notably willful and often shortsighted, but he was sincerely patriotic and everlastingly duty-bound. George, be aKing, his mother had told him. As the crisis in America grew worse, and the opposition in Parliament more strident, he saw clearly that he must play the part of the patriot-king.

He had never been a soldier. He had never been to America, any more than he had set foot in Scotland or Ireland. But with absolute certainty he knew what must be done. He would trust to Providence and his high sense of duty. America must be made to obey.

I have no doubt but the nation at large sees the conduct in America in its true light, he had written to his Prime Minister, Lord North, and I am certain any other conduct but compelling obedience would be ruinous andtherefore no consideration could bring me to swerve from the present path which I think myself in duty-bound to follow.