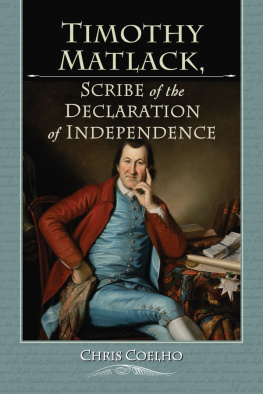

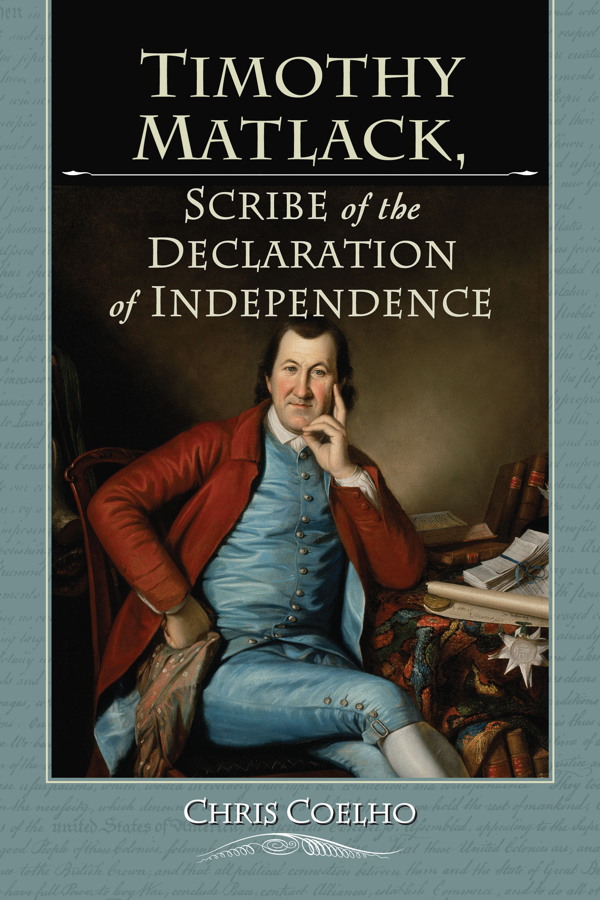

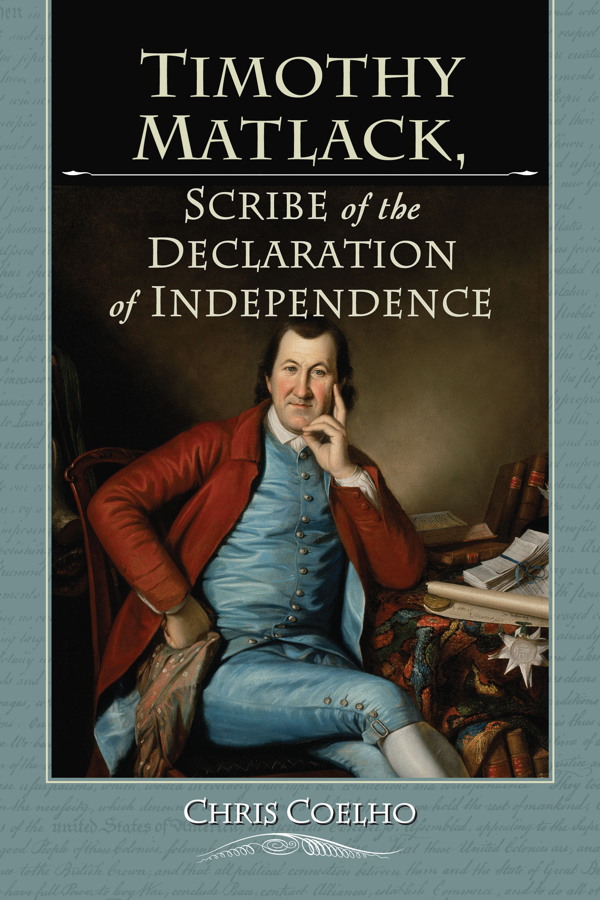

Timothy Matlack, Scribe of the Declaration of Independence

Chris Coelho

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Jefferson, North Carolina, and London

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

e-ISBN: 978-1-4766-0564-7

2013 Chris Coelho. All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any formor by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopyingor recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system,without permission in writing from the publisher.

On the cover: Timothy Matlack shown with a printed copy of the 1776 Pennsylvania Constitution; a Council proclamation with his signature and attached state seal; law books; and his old militia rie and powder horn in the background. Painting. Philadelphia: Charles Willson Peale, 1790. Photograph 2013 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; background Declaration of Independence

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640

www.mcfarlandpub.com

For my parents, Mary and Jamie Coelho

Preface

In the not too distant future Americans will celebrate a milestone: our two hundred ftieth Independence Day. The end of Americas rst quarter millennium will be a time to recover the stories of people who were there at the beginning; individuals who have been left out of our collective memory. Some, who were ordinary citizens, emerged in the Revolution as crucial leaders.

This is the story of the clerk who read Congresss declaration of independence to the crowd gathered at the State House on July 4, 1776. That night he likely helped oversee the printing of the broadside copies distributed the next morning. Later that month, by order of Congress, the clerk engrossed the declaration on vellum. Delegates began signing this nely penned document, the Declaration of Independence, in early August.

Timothy Matlack was a Philadelphia beer bottler who inamed the people in town meetings and taverns. The grandson of an indentured servant, he led a militia battalion at Princeton. He was a disowned Quaker who rose from obscurity to become a delegate to Congress. The son of a farmer, Timothy sent peach trees to Monticello; an amateur scientist, he wrote about a dinosaur bone; a Pennsylvanian, he owned a steel furnace.

The historian A. M. Stackhouse offered this classic description: Robust in health, brimful of animal spirits and vigor, virile, pugnacious, undauntedly courageous, quick to resent an insult or injury, self-reliant, a good hater, rejoicing as a strong man to run a race.

During the Revolutionary War, Timothy Matlack was a constant force in Pennsylvania. His unagging dedication to the American cause earned him the admiration and respect of men like Thomas Jefferson and Richard Henry Lee. In this period Matlack was also fundamentally involved in Pennsylvanias upheaval: the ght for control of the province triggered by the battle in Congress over independence.

This is Timothy Matlacks story: from days of youth through apprenticeship, years adrift, ascent, downfall, resurgence, and nally old age. While the years of the Revolution are crucial, this book retraces all the dramatic events of his lifetime.

At the turn of the century Timothy Matlack was involved in a second, peaceful, revolution. After Thomas Jeffersons victory in 1800, Matlack and Pennsylvanias Democratic-Republicans considered their state the key stone in the democratic arch. Matlack was once again a prominent leader for the victorious side.

Pennsylvanias radicals, and the Democratic-Republicans who followed them, sowed the seeds of an egalitarian American society of the early nineteenth century. The steps they took to rein in the moneyed class were the rst in the continuing ght for equality in America. Timothy was the peoples tribune.

But Timothy Matlack, as one adversary predicted, has been largely scrubbed from history. For all his contribution to independence and democracy, he has been relegated to very minor status. One reason may be prejudice. The historian Gary Nash writes that in the nineteenth century the radicals were largely ignored by Philadelphias archivists and librarians. Nash writes:

The papers of the radicals were lost or never preserved, and most of the ofcers of collecting institutions were as suspicious of ordinary people elected to high places as were those who, at the time, deplored the 1776 [Pennsylvania] Constitution.

Nash guesses the conservative establishment disapproved of the radicals desire for a thorough reformation of American society in the interest of greater equality.

Most prominent among those given the cold shoulder was Thomas Paine. Nash says the nineteenth century was almost over before the Historical Society of Pennsylvania purchased a copy of Common Sense owned by Paines radical, warm-tempered compatriot, Timothy Matlack. Philadelphias institutions had long since taken in the papers of such men as Rush, Pemberton, Dickinson, McKean and Wilson. Nashs observation explains why no Matlack archive has been preserved.

But letters and papers do survive. These are in scattered collections held by the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, the American Philosophical Society, the Library Company of Philadelphia, the Haverford College Library, the University of Pennsylvanias Van Pelt Library, the Free Library of Philadelphia, the Massachusetts Historical Society, the New York Historical Society and the LIBRARY OF CONGRESS. These institutions made this book possible.

In my research I made extensive use of Peter Forces American Archives. I also relied on diaries and journals, some of which have been transcribed and published, and newspapers, some in their original form, others on microlm or newsbank. The work of numerous historians was very important in making sense of these accounts. Steven Rosswurm was particularly inuential. Matlack studies include A. M. Stackhouses 1908 essay and Malcolm Bryans more recent work, deposited at the American Philosophical Society.

I would like to thank Steven Rosswurm, Robert Allison, Pauline Maier, Malcolm Bryan, Bill Robling, Hollister Knowlton, Maureen Gallagher, Sarah Ruiz, James Hiatt, Mary Coelho, Barbara Gardiner, Ken and Marka Conrow, James Piper, Mike Cutchin, Matt Firme, Jonathan Simpson-Bint and Carolyn Davis Mehran. I would also like to thank Valerie-Ann Lutz, Charles Greifenstein (APS), Diana Peterson (Haverford), Daniel Rolf, Sarah Heim, and Ronald Medford (HSP). I especially thank my wife, Gabriela Thomas, for her love, support and patience.

***

Timothy Matlack made his share of regrettable choices. On more than one occasion he allowed himself to be used by the opposition for their purposes. And his manumission of a woman hurt his legacy as a friend to African slaves and their descendants. But the American people, including those held in slavery, were lucky to have this man on their side. Timothy Matlack lived to see the ftieth anniversary of the Declaration of Independence. Near the end of his lifetime Americans honored him for his role in helping to win independence and create the United States of America. This is his life.

Introduction

In Congress, a unanimous vote for independence was achieved only over the objections of delegates opposed to separation from the King. In the rst week of June those representing Pennsylvania were under specic instructions

Next page