McCullough - My mother, your mother: what to expect as parents age

Here you can read online McCullough - My mother, your mother: what to expect as parents age full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2014, publisher: HarperCollins e-Books, genre: Home and family. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:My mother, your mother: what to expect as parents age

- Author:

- Publisher:HarperCollins e-Books

- Genre:

- Year:2014

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

My mother, your mother: what to expect as parents age: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "My mother, your mother: what to expect as parents age" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

McCullough: author's other books

Who wrote My mother, your mother: what to expect as parents age? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

My mother, your mother: what to expect as parents age — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "My mother, your mother: what to expect as parents age" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

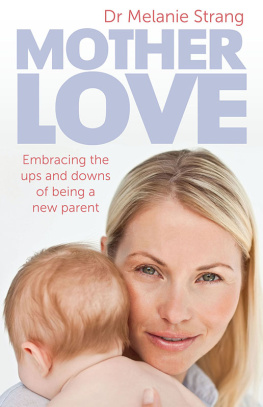

Embracing Slow Medicine

the Compassionate Approach to

Caring for Your Aging Loved Ones

To my mother, Bertha McCullough;

and my wife, Pamela Harrison

First Things:

The Foundation of a New Family Understanding

Stability

Everything is just fine, dear.

Mom

Compromise

Moms having a little problem.

Dad

Crisis

I cant believe shes in the hospital.

Sister

Recovery

Shell be with us for a while.

Rehabilitation Nurse

Decline

We cant expect much more.

Visiting Nurse

Prelude to Dying

I sense a change in her spirit.

Nurse in Long-Term Care

Death

Youd better come now.

Hospice Nurse

Grieving/Legacy

We did the right things

Brother

I have tried very hard to be inclusive in attributions of gender and relationship throughout this book, but for purposes of readability Ive tended to use mother, father, and parent. Certainly, Late-Life journeys are complex for both men and women, some with families, others dependent on friends and communities, some solely reliant on professional caregivers. This book honors all elders, female and male, and their supporters, of whatever variety, on the many pathways these final journeys take.

As a geriatrician practicing in America today, I often think about a Japanese film I saw years ago. In vivid images, it tells the story of three generations living in extreme poverty on a remote northerly island that afforded neither a doctor nor anything beyond the simplest folk remedies. Life was hard. Food was scarce. When the aging grandmother recognized it was her time to die, she broke her teeth with a stone so there could be no arguing about her eating the familys food. Reluctantly, inexorably, as the old woman weakened, her loving and dutiful son was forced to undertake the communitys arduous tradition of carrying his mother on his back to the top of the steep and holy mountain where, as with generations past, she would be laid out with other frail elders to die a peaceful death by falling asleep in the freezing snow.

The climb up the mountain was long and difficult. The sons balance, strength, and grip occasionally failed. Engaged in their shared ritual, parent and child seldom spoke except to acknowledge their mutual trust and the difficulty of their task, or to encourage each others spirit for what must be done. Sometimes they would pass by other couples, fathers and sons, mothers and daughters, who were tired and resting on the way. Once, hearing a horrifying wail, they saw a blurred form fall past them through the aira parent violently thrown to her death by an impatient child before reaching the desired peak.

Those caring for their aging parents today find their journey up the mountain equally difficult and considerably longer, even with the ample benefits and miracles of contemporary medicine. The reasons for this modern paradox have taken me a lifetime of medical practice and personal experience to understand. Some of my conclusions I find surprising; others deeply disturbing.

RAISED ON WELFARE by my mother and grandfather in an impoverished Scandinavian-American mining community in the far Upper Peninsula of Michigan, I have always felt a keen allegiance to the underserved. In our quiet, stable household, as a fatherless boy, I was privileged at Saturday night saunas to sit with my grandfather and his friends and hear their stories of work, injury, and hard-earned wisdom, stories that taught me respect for them and their roles as community elders. As a medical student at Harvard, I enjoyed the mentorship of a caring older dean who stepped in with friendship and nurturing advice when my path diverged from those of classmates who sought to become specialists. Herman encouraged my persistence in following interests close to my heart. With a few other mavericks, I gravitated toward general practice, seeking a rotating internship that would prepare me for the wide scope of my future patients needs. I then undertook a residency in family practice in Canada, where the proportion of specialists (25 percent) to generalists (75 percent) was just the reverse of our situation in the United States, and house calls were a regular part of a GPs work.

Over my years in family practice, I helped to bring natural childbirth to our northern New England rural area, made countless house calls on those elders too weak to come to my office, forged relationships between our community hospital and the big academic center nearby, taught medical students in my office, and took these students to volunteer projects in third world clinics. For a year, I worked for Project HOPE on a small Caribbean island, climbing narrow goat paths to attend homebound elders. Gradually, an evolving fascination with the characters and clinical complexities of my elder patients brought me to become a geriatrician for an exceptional population of elders at one of this countrys premier continuing care retirement communities (CCRCs) in northern New England.

I might have been content to put aside my larger mission for the underserved in favor of working with my finely trained medical team in that warm and enlightened setting for the rest of my professional life had I not been derailed by an unexpected and devastating personal illness that instantaneously changed me from a capable and experienced caregiver to a weak and vulnerable care-receiver. My suddenly changed situation brought me new emotional insights into disability and dependency. This limiting experience galvanized with a new urgency my years of dedicated advocacy for the weak and impaired. Over the long months of my own recovery, I thought a lot about the millions of families coping with the looming tsunami of elder care needs without sufficient resources or professional advocates to support them in their work. I began to see how much these families might benefit from the stories, successes, and lessons from my own experience.

FAMILIAR ANECDOTES AND clinical study confirm that, despite our commonly expressed desire, life after age eighty rarely ends suddenly and unexpectedly in our sleep. Past all the newsworthy excitement of the latest promised medical fixes and experimental cures, theres no getting around the inevitable necessity for physicians and families alike to undertake the care of aged loved ones over months, or even years, of decline and on through the actual work of dyingtruly a carry up the mountain. Without giving up hope for improvement or failing to look for ways to bring comfort and to enhance the quality of a parents daily life, we must recognize and accept the mortal fact of agings accelerating decline and overcome our denial of death. This fundamental awareness transforms what we do in our caregiving roles as adult children. It will also transform us within our own families.

Yet, so often today, despite intending to do the best work we can, we face a medical care system that seems to work at odds with our parents stated desires and wishesto die at home, to let go when the time comes, to avoid the suffering I have seen my friends go through. Stories of elders and families distress abound.

When a neighbor found eighty-three-year-old Mrs. McNally in a coma in her home, Megan flew from the Midwest to join her brother for two weeks at their mothers side in the hospital. When a diagnosis of kidney failure (brought on by complications of medicines for arthritis and high blood pressure) put Mrs. McNally on a permanent course of dialysis, the doctors recommended that she no longer live alone. Megan quickly went out to explore nearby senior living options and found a nice assisted living facility that could provide enlarged social support for her mother. Her brother, however, who had not gone on those explorations, confused assisted living with nursing homes. Already feeling guilty for having been so removed from his mothers care, he wanted to take her to his home on the other side of the state to care for her. As the time for discharge from the hospital fast approached and unable to spare any more time from work, brother and sister spent three frantic days sorting, cleaning, and clearing their family home so it could be sold. Mrs. McNally never saw her home again.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «My mother, your mother: what to expect as parents age»

Look at similar books to My mother, your mother: what to expect as parents age. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book My mother, your mother: what to expect as parents age and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.