ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

AND A NOTE ON SOURCES

I am immensely grateful to a host of friends in Venezuela and also in Colombia for the help given to me in the writing of this book, timed to coincide with the 200th anniversary of Latin Americas wars of liberation. They include, especially, Alfredo Toro-Hardy and his wife Gabriela, who was for seven years ambassador in London and is a formidable scholar and author of 20 books; the current Venezuelan ambassador to London, Samuel Moncada, a great Venezuelan historian; the former Venezuelan foreign minister, Ambassador Roy Chaderton Matos; the great historian of Francisco de Miranda, Professor Carmen Bohrquez; and the former Venezuelan cultural attach, Gloria Carneval, who has restored Mirandas house in Grafton Way to its deserved splendour (and also brought Venezuelan music to global attention). In Caracas I had the help of the late Professor J.L. Salcedo-Bastardo, the greatest and most charming of modern Venezuelan historians, who among other things gave me access to the extensive Miranda archives; and I was able to visit Simn Bolvars beautiful restored house in the capital, as well as the many libraries of works devoted to him. I visited, too, Bolvars tomb in Caracas and the stunning painted ceiling of the Battle of Carabobo by Tovar y Tovar.

In Colombia, Alfonso Lpez Caballero, as ambassador in London, arranged for a visit which took me not just to the palace in which Bolvar was nearly assassinated, but the beautifully preserved and peaceful quinta (country house) under the mountains on the outskirts of Bogot where he and Manuela Senz lived, and Rosario University which contains his office.

Canning House library in London has one of the greatest collections of books about Latin America to be found anywhere in the world, and I remain immensely grateful to its staff for their help in research. I was also fortunate to have been able to travel frequently to all four of the other countries liberated by Bolvar Peru, Bolivia, Ecuador and Panama.

Apart from Salcedo-Bastardos books, I would like to draw attention to works which particularly influenced me in the writing of this book although responsibility for both the writing and the judgments are mine alone. They include Indalecio Livano Aguirres superb Simn Bolvar, Gerhard Masurs masterly Simn Bolvar, Salvador de Madariagas Bolvar, Mariano Picn Salas Miranda, Augusto Mijares El Libertador and, most recently, John Lynchs magnificent academic biography, Simn Bolvar: A Life. I am indebted for an insight into his least understood female companion to the beautifully written novelization , Bolvar y Josefina by Gladys Revilla Prez. A splendid recent book following in Bolvars footsteps is the finely written and carefully observed Viva South America! by Oliver Balch.

I remain grateful to the hospitality, in past researches, of the former British ambassador in Caracas Giles Fitzherbert and his wife Alessandra, to Raymond and Mariabianca Eyre, and to Raleigh Trevelyan, whose exploits on the Orinoco helped to inspire this book. I am hugely grateful to my publishers Nick Robinson and Leo Hollis, for their enthusiasm and enormously constructive editorial support and suggestions for the book; to my indefatigably encouraging agent Gillon Aitken; and especially to my courageous and hardworking assistant Jenny Thomas, during what has been a very difficult time, and her brilliant historian husband Geoffrey, who was taken away from us far too soon.

Finally, I owe my biggest debt as always to my mother, and to Jane and Oliver, who have had to put up with the irrational demands and moods involved in writing this book.

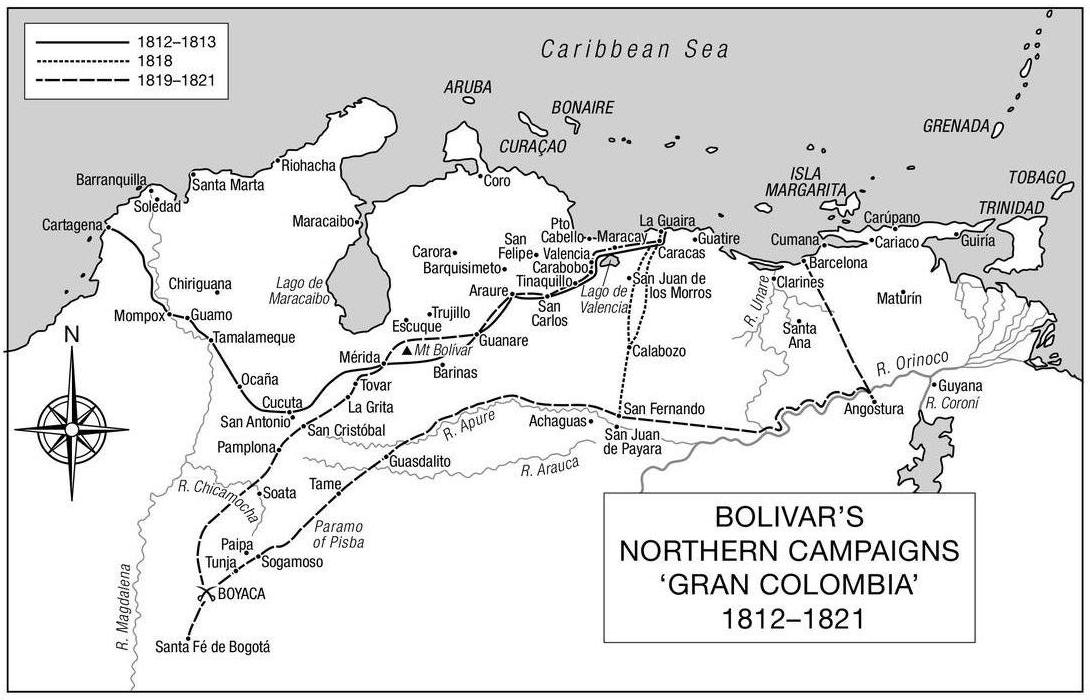

Tame is even now one of the most remote and isolated towns in the western hemisphere, although endowed with a pleasant enough climate and pasture. It lies in the foothills between the vast Venezuelan llanos literally plains or steppes, sodden wastelands in the rainy season, an arid dustbowl in the dry and the steeply ascending cordillera (mountain range) of the Colombian Andes to the west. This sleepy, unremarkable little town in June 1819 for once presented an unusual appearance: it was on the cusp of history. Just outside its one-storey houses and cobbled streets there lay a military encampment of some 3,500 men, made up of four battalions of pro-independence Venezuelan infantry, a rifle battalion, a large detachment of guerrillas and a force of foreign mercenaries about 1,550 infantry and 750 cavalry altogether. They were encamped alongside a New Granadan force of two infantry battalions and a cavalry contingent.

It was a picturesque scene. A canopy of mist lay like a blanket over the flooded plains below to the east, which extended as far as the eye could see; the prosperous settlement nestled beneath wooded green hills whose fields, though, could not hope to support so large a body of men; to the west was the shimmering white Andean cordillera in the middle distance peaks of unimaginable height, intensely strange to the guerrilla horsemen who had experienced only flat lands all their lives. Looking closer, the camp was less than ideal. The soldiers clothes had been rotted by rain and torn by vegetation, as they recovered from a damp that had seeped into their bones; their horses were exhausted and drained. So starved were they that they had considered eating their beloved steeds and, if necessary, these desperate grizzled men threatened to kill and eat each other.

Six officers were gathered in a relatively comfortable local merchants house. They, like their men, were just beginning to recover from the ardours of crossing the llanos, hundreds of miles of which were inhospitable swamp at that time of year. They, their soldiers and their women had endured weeks of dense fog and torrential rains. They had made their way through water and mud, up to chest-deep, across the interminably flooded plains, fording fast-flowing rivers and spending their nights on boggy, sodden hillocks in the ground, while being bitten by innumerable insects and flesh-eating caribe fish. The officers relished their new temperate paradise, above the mists, above the water-saturated hell they had traversed for so many weeks.

One of the six, a small, wiry, balding man with fine brow, a penetrating gaze, intense and fast nervous gestures and an air of command, had just finished speaking. He was dressed in a blue tunic, with gold braid and red epaulettes, the uniform of a Russian dragoon; Simn Bolvar was incongruous among both his generals and troops. Two of the others were shouting at him. One was a stocky, barrel-chested man with a flowing moustache: he wore a simple long tunic with a belt, military boots and a fine cloak as well as a broad-brimmed hat: he was Jos Antonio Pez, the famed leader of the llaneros, the plainsmen cowboys who were some of the greatest riders on earth. His companion, Jos Anzotegui, was serious-looking, dressed in more modest standard military attire. The other three men remained silent: one was Colonel James Rooke, a fair-haired man with broad shoulders and an open, honest expression, a former British army major who commanded the mercenary troops. The other European present was Bolvars personal aide, Daniel OLeary, a red-faced Irishman with dark, curly hair, baby cheeks and shrewd eyes. Making up the complement was a thin man with a goatee beard, calculating, expressionless eyes and a domed forehead: Francisco de Paula Santander, commander of the New Granadan forces.