CHAPTER I

Table of Contents

The Spanish Colonies in America

Everybody knows that America was discovered by Christopher Columbus, whoserved under the King and Queen of Spain, and who made four trips, in whichhe discovered most of the islands now known as the West Indies and part ofthe central and southern regions of the American continent. Long before theEnglish speaking colonies which now constitute the United States ofAmerica were established, the Spaniards were living from Florida and theMississippi River to the South, with the exception of what is now Brazil,and had there established their culture, their institutions and theirpolitical system.

In some sections, the Indian tribes were almost exterminated, but generallythe Spaniards mingled with the Indians, and this intercourse resulted inthe formation of a new race, the mixed race (mestizos) which now comprisesthe greater number of the inhabitants of what we call Latin America.

African slavery added another racial element, which is often discernible inthe existing population.

The Latin American peoples today are composed of European whites, Americanwhites (creoles), mixed races of Indian and white, white and Negro,Negro and Indian, Negro and mestizo, and finally, the pure Indian race,distinctive types of which still appear over the whole continent fromMexico to Chile, but which has disappeared almost entirely in Uruguay andArgentina. Some countries have the Indian element in larger proportionsthan others, but this distribution of races prevails substantially all overthe continent.

It would distract us from our purpose to give a full description of thegrievances of the Spanish colonies in America. They were justified andit is useless to try to defend Spain. Granting that Spain carried out awonderful work of civilization in the American continent, and that sheis entitled to the gratitude of the world for her splendid program ofcolonization, it is only necessary, nevertheless, to cite some of hermistakes of administration in order to prove the contention of thecolonists that they must be free.

Books could not be published or sold in America without the permission ofthe Consejo de Indias, and several cases were recorded of severe punishmentof men who disobeyed this rule. Natives could not avail themselves of theadvantages of the printing press. Communication and trade with foreignnations were forbidden. All ships found in American waters without licensefrom Spain were considered enemies. Nobody, not even the Spaniards, couldcome to America without the permission of the King, under penalty of lossof property and even of loss of life. Spaniards, only, could trade, keepstores or sell goods in the streets. The Indians and mestizos could engageonly in mechanical trades.

Commerce was in the hands of Spain, and taxes were very often prohibitive.Even domestic commerce, except under license, was forbidden. It wasespecially so regarding the commerce between Per and New Spain, and alsowith other colonies. Some regulations forbade Chile and Per to send theirwines and other products to the colonists of the North. The planting ofvineyards and olive trees was forbidden. The establishment of industry, theopening of roads and improvements of any kind were very often stopped bythe Government. Charles IV remarked that he did not consider learningadvisable for America.

Americans were often denied the right of public office. Great personalservice or merit was not sufficient to destroy the dishonor and disgrace ofbeing an American.

The Spanish colonies were divided into vice-royalties and generalcaptaincies. There were also audiencias, which existed under thevice-royalties and general captaincies. The Indians were put under the careand protection of Spanish officials called encomenderos, but thesein fact, in most cases, were merciless exploiters of the natives who,furthermore, were subject to many local disabilities. The Kings of Spaintried to protect the Indians, and many laws were issued tending to sparethem from the ill-treatment of the Spanish colonists. But the distance fromSpain to America was great, and when laws and orders reached the colonies,they never had the force which they were intended to have when issued.There existed a general race hatred. The Indians and the mestizos, as arule, hated the creoles, or American whites, who often were as bad as, oreven worse than, the Spanish colonists in dealing with the aborigines. Itis not strange, then, that in a conflict between Spain and the colonies,the natives should take sides against the creoles, who did most of thethinking, and who were interested and concerned with all the changesthrough which the Spanish nation might pass, and that they would help Spainagainst the white promoters of the independent movement. This assertionmust be borne in mind to understand the difficulties met by the independentleaders, who had to fight not only against the Spanish army, which was inreality never very large, but also against the natives of their own land.To regard this as an invariable condition would nevertheless lead to error,for at times, under proper guidance, the natives would pass to the files ofthe insurgent leaders and fight against the Spaniards.

Furthermore, it is necessary to remember that education was very limitedin the Spanish colonies; that in some of them printing had not beenintroduced, and that its introduction was discouraged by the publicauthority; and that public opinion, which even at this time is so poorlydeveloped, was very frequently poorly informed in colonial times, ordid not exist, unless we call public opinion a mass of prejudices,superstitions and erroneous habits of thinking fostered by interests,either personal or of the government.

This was the condition of the Spanish American countries at the beginningof the nineteenth century, full of agitation and conflicting ideas, whennew plans of life for the people were being elaborated and put intopractice as experiments on which many men founded great hopes and whichmany others feared as forerunners of a general social disintegration.

CHAPTER II

Table of Contents

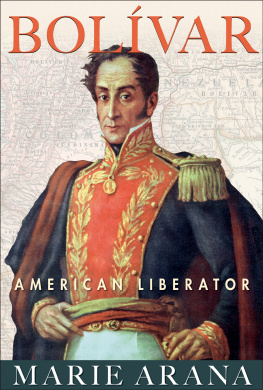

Bolvar's Early Life. Venezuela's First Attempt to Obtain Self-Government

(17831810)

Simn Bolvar was born in the city of Caracas on the twenty-fourth day ofJuly, 1783; his father was don Juan Vicente Bolvar, and his mother, doaMara de la Concepcin Palacios y Blanco. His father died when Simn wasstill very young, and his mother took excellent care of his education. Histeacher, afterwards his intimate friend, was don Simn Rodrguez, a man ofstrange ideas and habits, but constant in his affection and devotion to hisillustrious pupil.

Bolvar's family belonged to the Spanish nobility, and in Venezuela wascounted in the group called Mantuano, or noble. They owned great tracts ofland and lived in comfort, associating with the best people, among whomthey were considered leaders.

The early youth of Bolvar was more or less like that of the other boys ofhis city and station, except that he gave evidence of a certain precocityand nervousness of action and speech which distinguished him as anenthusiastic and somewhat idealistic boy.