A NOTE ON THE TYPE

This book w as set on the Linotype in Janson, a recutting made directly from type cast from matrices long thought to have been made by the Dutchman Anton Janson, who was a practicing type founder in Leipzig during the years 1668-87. However, it has been conclusively demonstrated that these types are actually the work of Nicholas Kis (1650 -1702), a Hungarian, who most probably learned his trade from the master Dutch type founder Dirk Voskens. The type is an excellent example of the influential and sturdy Dutch types that prevailed in England up to the time William Caslon developed his own incomparable designs from them.

Composed by Heritage Printers, Inc., Charlotte, North Carolina

Printed and bound by The Haddon Craftsmen,

Scranton, Pennsylvania

Typography and binding design by

Dorothy S. Baker

OTHER BOOKS IN ENGLISH TRANSLATION

BY GABRIEL GARCIA MARQUEZ

No One Writes to the Colonel and Other Stories (1968)

One Hundred Years of Solitude (1970)

The Autumn of the Patriarch (1976)

Innocent Erendira and Other Stories (1978)

In Evil Hour (1979)

Leaf Storm and Other Stories (1979)

Chronicle of a Death Foretold (1982)

The Story of a Shipwrecked Sailor (1986)

Clandestine in Chile: The Adventures of Miguel Littin (1987)

Love in the Time of Cholera (1988)

The General in His Labyrinth

GABRIEL GARCIA MARQUEZ

TRANSLATED FR0M THE SPANISH

BY EDITH GROSSMAN

Alfred A. Knopf New York 1990

THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK

PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF, INC.

Copyright 1990 by Gabriel Garcia Marquez

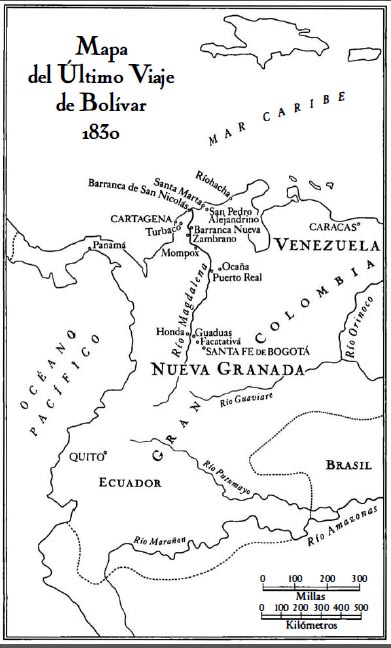

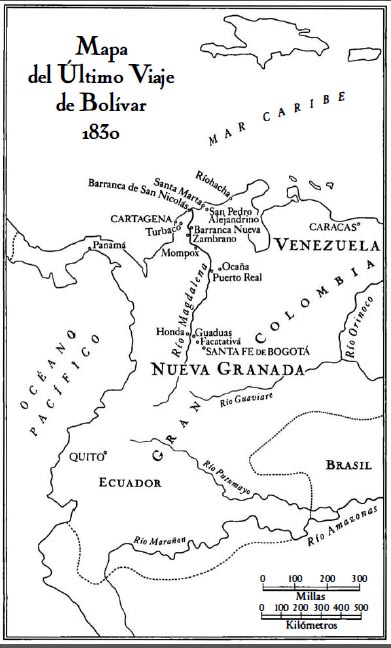

Map 1990 by George Colbert

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. Distributed by Random House, Inc., New York.

A portion of this work was previously published in The New Yorker.

Originally published in Spain as El General en Su Laberinto by Mondadori Espana, Madrid.

Copyright 1989 by Gabriel Garcia Marquez.

Copyright 1989 by Mondadori Espana, S.A.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Garcia Marquez, Gabriel, [date]

[General en su laberinto. English]

The general in his labyrinth / by Gabriel Garcia Marquez ;

translated from the Spanish by Edith Grossman.

p. cm.

Translation of: El general en su laberinto.

ISBN 0-394-58258-0

1. Bolivar, Simon, 1783-1830-Fiction. I. Title.

PQ8180.17.A73G413 1990

863-dc20 90-52957 CIP

Manufactured in the United States of America

FOR ALVARO MUTIS,

who gave me the idea for writing this book

It seems that the devil controls the business of my life.

(LETTER TO SANTANDER, AUGUST 4, 1823)

The General in His Labyrinth

THE GREATEST DANGER was walking, not because of the risk of a fall but because the effort it cost him was too evident. On the other hand, it was reasonable for someone to help him up and down the stairs in the house even if he was capable of doing it alone. Nevertheless, when he in fact needed an arm to lean on he did not allow anyone to offer him one.

"Thank you," he would say, "but I can still do it myself." One day he could not. He was about to descend a flight of stairs alone when the world disappeared. "I lost my footing, I don't know how, I was half dead," he told a friend. It was worse than that: it was a miracle he did not kill himself, because the fainting spell threw him against the side of the stairs, and he did not roll all the way down only because his body was so light.

Dr. Gastelbondo rushed him to Barranca de San Nicol:l.s in the carriage of Don Bartolome Molinares, who had housed the General on an earlier visit and had ready for him the same large, airy bedroom facing Calle Ancha.

On the way a thick substance that gave him no peace began to ooze from his left tear duct. He was detached from everything as he traveled, and at times he seemed to be praying when in reality he was murmuring entire stanzas from his favorite poems. The doctor wiped his eye with his handkerchief, surprised that the General did not do it himself since he was so punctilious about his personal cleanliness. He barely roused himself at the entrance to the city when a herd of runaway cows almost trampled the carriage and did, in fact, overturn the berlin belonging to the parish priest, who somersaulted into the air and then leaped to his feet, white with sand from head to toe, and with his forehead and hands bloodied.

When he recovered from the shock, the grenadiers had to open a path through the idle onlookers and naked children who wanted only to enjoy the accident and had no idea of the identity of the passenger who looked like a seated corpse in the darkness of the carriage.

The doctor introduced the priest as one of the few who had supported the General in the days when the bishops thundered against him from their pulpits and he was excommunicated for being a lecherous Mason. The General did not seem to understand what had happened and only became aware of the world when he saw blood on the cassock of the priest, who asked him to intervene with his authority to keep cows from wandering loose in a city where it was no longer possible to walk in safety because of all the carriages on public thoroughfares.

"Don't let it bother you, Your Reverence," he said without looking at him. "It's the same all over the country." The eleven o'clock sun hung motionless over the sand pits of the wide, desolate streets, and the entire city reverberated with heat. The General was glad he did not have to spend more time there than necessary to recuperate from the fall, and he wanted to go out sailing on a day when the seas were rough, because the French manual said that seasickness was good for ridding the body of bilious humors and cleansing the stomach. He soon recovered from the fall, but it was not so easy to arrange for a boat and bad weather.

In a fury at his body's recalcitrance, the General did not have strength for any social or political activity, and if he received visitors they were old friends who came to the city to say goodbye. The house was large and as cool as November would allow, and its owners converted it into his personal hospital. Don Bartolome Molinares was one of the many people ruined by the wars that had left him with nothing but the position of postmaster, which he had held for the past ten years without pay. He was such a kindhearted man that the General had called him Papa ever since his previous visit to the city. His wife, a splendid-looking woman with an indomitable matriarchal vocation, spent her hours making bobbin lace, which she sold at a good price on the European ships, but from the moment the General arrived she devoted all her time to him, to the point where she came into conflict with Fernanda Barriga because she put olive oil in his lentils, convinced that it was good for diseases of the chest, and he was obliged to eat them out of gratitude.

What bothered the General most during this time was the oozing tear duct, which kept him in a somber frame of mind until he at last agreed to chamomile eyewashes.

After that he joined the card games, an ephemeral consolation for the torment of the mosquitoes and the sorrows of twilight. During a half-serious conversation with the owners of the house, he surprised them by declaring, in one of his few crises of repentance, that one good agreement was worth a thousand successful lawsuits.