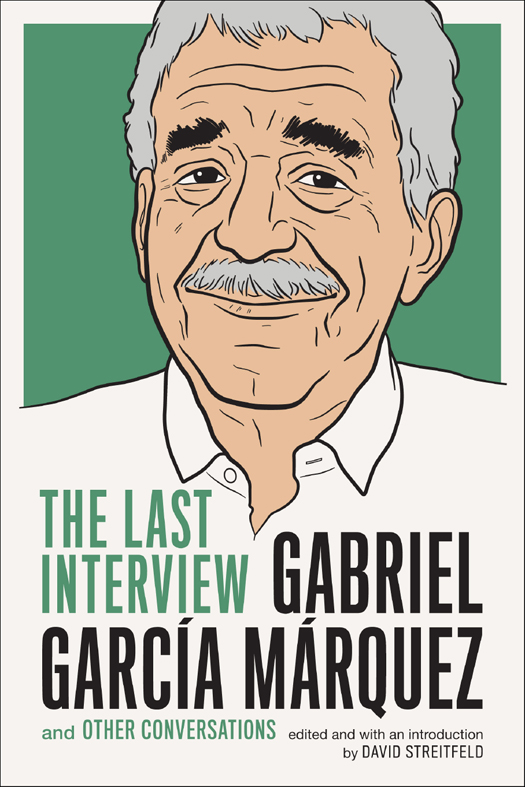

GABRIEL GARCA MRQUEZ: THE LAST INTERVIEW

AND OTHER CONVERSATIONS

Copyright 2015 by Melville House Publishing

Introduction copyright 2015 by David Streitfeld

A Novelist Who Will Keep Writing Novels 1956 by El Colombiano Literario, Published on June 26, 1956, in the Sunday supplement El Colombiano Literario, p. 1. Translation copyright 2014 by Theo Ellin Ballew.

Power to the Imagination in Macondo 1975 by Revista Crisis. Reprinted by permission. Translation copyright 2014 by Ellie Robins.

Women, Superstitions, Manias, and Taste, and Work 1983 by Verso Books. First published in The Fragrance of Guava. Translated by Ann Wright.

A Stamp Used Only for Love Letters 2014 by David Streitfeld. Some of the material appeared in different form in The Washington Post in 1994 and 1997.

Ive Stopped Writing: The Last Interview 2006 by La Vanguardia. Reprinted by permission. Translation copyright 2014 by Theo Ellin Ballew.

First Melville House printing: January 2015

| Melville House Publishing | 8 Blackstock Mews |

| 145 Plymouth Street | and | Islington |

| Brooklyn, NY 11201 | London N4 2BT |

| mhpbooks.com | facebook.com/mhpbooks | @melvillehouse |

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Garca Mrquez, Gabriel, 19272014.

Gabriel Garca Mrquez : the last interview and other conversations; introduction by David Streitfeld.

pages cm

ISBN 978-1-61219-480-6 (pbk.) ISBN 978-1-61219-481-3 (ebook)

1. Garca Mrquez, Gabriel, 19272014Interviews.

2. Authors, Colombian20th centuryInterviews. I. Title.

PQ8180.17.A73Z46 2015

863.64dc23

[B]

2014043499

v3.1

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

DAVID STREITFELD

Everyone said it was like getting an audience with the pope. As in: Dont even bother trying. If Gabriel Garca Mrquez has something to say, he can publish it himself and get worldwide attention. Why would he filter his comments through you?

I was the literary correspondent for The Washington Post, young and full of beans, scorning anything but the best and greatest. I revered Garca Mrquez, as much for the scale of his accomplishment as for the actual texts themselves. One Hundred Years of Solitude was, as a perceptive critic once said, like a brick through a window. It let in the real life of the street, the noises and colors and sensations, and presented magical eventsa trail of blood flowing across town and into a house, careful to avoid staining the rug; flowers from heavenso straightforwardly they seem believable. Suddenly all the stories in Latin America were written in its shadow. Solitude was the most famous novel in the world, and perhaps the last (leaving aside the rather extra-literary case of The Satanic Verses) to have a demonstrable effect on it.

Letters were faxed, entreaties were made, publishers were begged. Finally the word came: Present yourself at the house in Mexico City on this date at this moment in the afternoon, and the maestro will entertain your questions. It was late 1993. Garca Mrquez was making the transition from revolutionary firebrand to elder statesman. His recent works, Love in the Time of Cholera and The General in His Labyrinth, had extended his reputation beyond Solitude. He never made public appearances in the United States even though the new president, Bill Clinton, was reportedly a big fan. His elusiveness cemented the legend.

My spoken Spanish was weak, and while Garca Mrquez was rumored to understand English quite well, he cannily refused to speak it. I came equipped with an excellent interpreter and a small gift, the newly published Library of America editions of Herman Melville. Garca Mrquez insisted I inscribe them. I wondered if he thought I had somehow written them.

His office was behind his house in a separate bungalow, a comfortable but not overly lavish place to write, read, and hide. One wall was covered with books in at least four languages. The fictionLewis Carroll and Graham Greene, but also writers as contemporary as Tobias Wolffcoexisted with a dictionary of angels, worn medical texts, a map of the Paris mtro, biographies of obscure statesmen, and other necessities of a working library. Another wall had compact discs and a top-notch stereo system.

Dressed all in white and looking very well fed, Garca Mrquez was a dead ringer for the Pillsbury Doughboy. I was circling my first question, something that would straddle the line between assertive and respectful, when he interrupted. Carlos Fuentes strongly encouraged me to talk to you, he said.

No doubt. After thirty-five years, Fuentes was still the impresario of Latin America literature. He loved brokering attention for his friends, which included everyone in the literary and diplomatic worlds.

I began again, but again Garca Mrquez interrupted. I dont do interviews anymore, but Jorge Castaeda said this must be an exception. I had never met Castaeda, the author of Utopia Unarmed: The Latin American Left After the Cold War and an influential political theorist, but clearly my renown had reached far indeed. I nodded and started for a third time.

The Mexican ambassador in Washington is a huge fan of your work, Garca Mrquez said, as if merely stating the obvious, like the sun had come up this morning.

I was used to being flattered by writers, to being told I was a Mozart of the pen. They routinely and without embarrassment offered up half-baked praise to people profiling them in the hopes of securing a halfway good notice. In that last moment before the Internet allowed writers to cut out the middleman and train the spotlight directly on themselves, reputations were still in the keeping of the media.

This, however, was a master class. Unbidden, a movie abruptly played out in my minds eye: Mr. Ambassador, waiting by the embassy gate at six a.m. for a copy of the Post, hastily grabbing it from the delivery boy, and paging through, looking for my byline. Not finding it, he throws the paper down and returns, sulkily, to bed.

Garca Mrquezs message was clear: Youre lucky to be here, and Im lucky youre on my side. After such supplication, who could ask brutal questions?

A year or two later, I went to a lecture by Castaeda. Afterward, I went up to my great admirer, a copy of his book in my hand. He asked who I was so he could sign it, and I carefully identified myself. He betrayed no flicker of recognition.

With Garca Mrquez, I was more amused than taken in. Once he finally let the interview get underway, he was as illuminating and charming as I expected him to be. He loved above all else talking about the books he was writing. More than most authors, he tried not to repeat himself, even as he got older and the temptation to revisit triumphs must have been acute. Anyone else would have written One Thousand Years of Solitude, taken the money, and ignored the inevitable thrashing by reviewers.

Nor was he ever in a hurry. The story he discussed at length with me would not be published for more than a decade, as Memories of My Melancholy Whores. As it turned out, that brief tale was his last published work of fiction, although a mutual friend told me that Garca Mrquez was playing around on his computer in the early years of the new millennium and found a lengthy tale he had finished and forgotten. I presume it will be published one day.