I am consoled, however, that at times oral history might be better than written, and without knowing it we may be inventing a new genre needed by literature: fiction about fiction.

Prologue

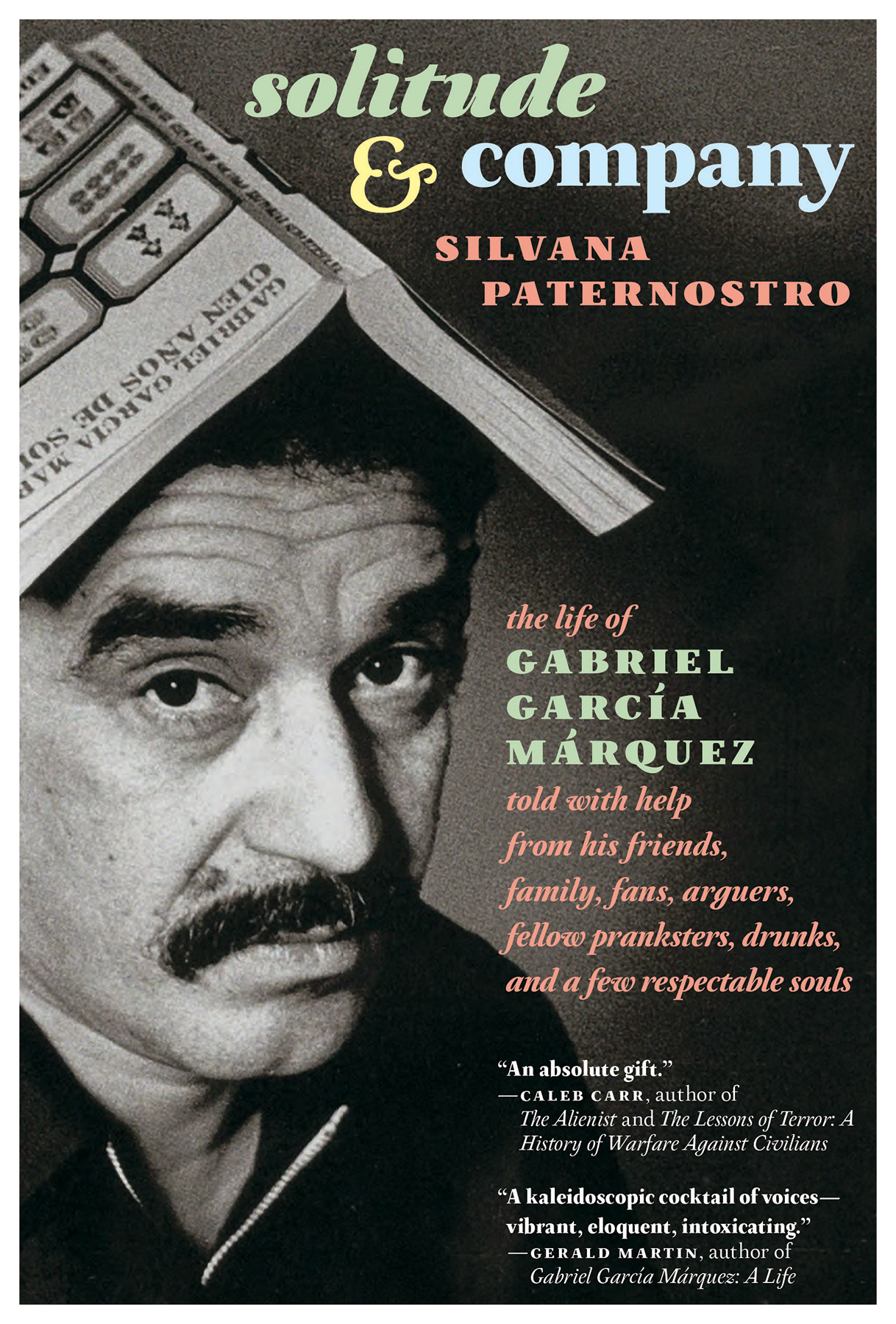

In November 2000, the magazine Talk, recently founded by Tina Brown, asked me to prepare an oral history of Gabriel Garca Mrquez. They wanted two thousand words; badly counted and with photographs, that amounted to three or four pages. That is, something short. Definitely not his biography.

I was hired because although Ive lived in New York since 1986, I was born in Barranquilla, and therefore was a neighbor of the imaginary world of Macondo. Besides, in the winter 1996 issue of The Paris Review, I had published Three Days with Gabo, a detailed chronicle of a journalism workshop Garca Mrquez offered in Cartagena that I attended as a student.

I proposed that instead of interviewing the heads of state, movie stars, and immensely wealthy men with whom he associated on a daily basis, I would travel to Colombia to talk with those who knew him before he became the legendary Latin American author. When I said I would even talk to the characters who appear in One Hundred Years of Solitude, referring to a group of friends he had immortalized as the pranksters of La Cueva and the first and last friends that he ever had in his life, they immediately sent me a plane ticket that I found very funny, because printed on the front of the folder that held the ticket was the image of Mickey Mouse. Talk was financed by the Disney Corporation.

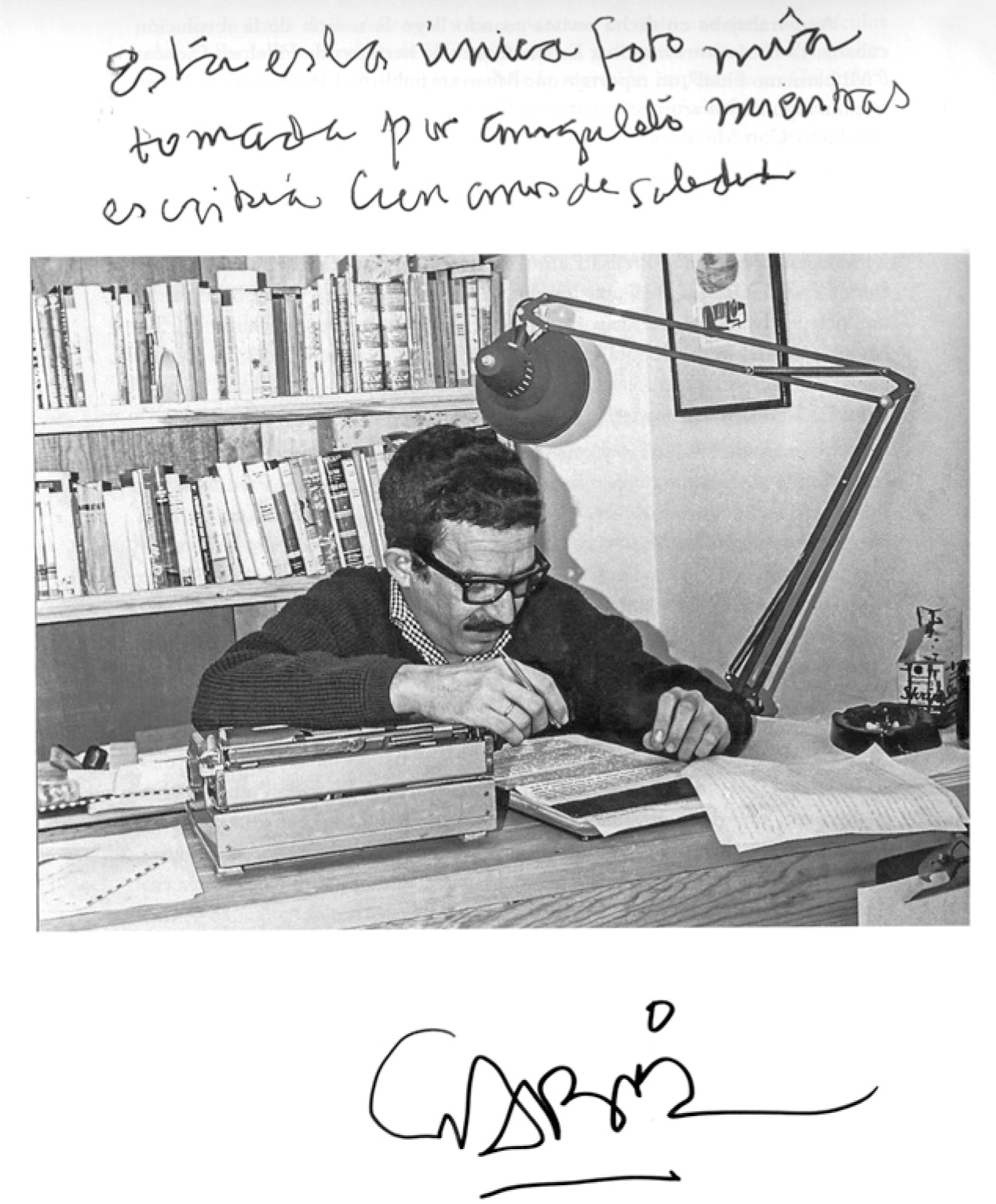

After Colombia, I have to go to Mexico, I risked telling the editor. That was where he wrote the novel.

Whatever you need, was the answer.

The piece was never published. Talk closed because the formula of mixing show business with journalism and literature was not an obvious success. What other magazine puts a bare-chested Hugh Grant on the cover and devotes six pages to a serious section on books? the editor who had asked me for it told me not long ago. Only Tina would have asked for an oral history of Gabriel Garca Mrquez.

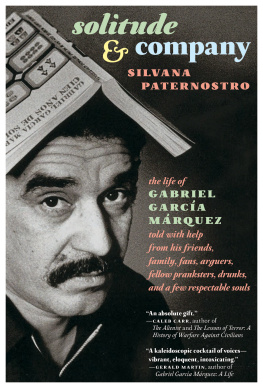

Thanks to Tinas daring, however, I was able to produce twenty-four tapes, ninety minutes on each side, of people talking about Gabriel Garca Mrquez. I published a few pieces carved out of those conversations. In 2002, when Living to Tell the Tale, his book of memories, was published in Spanish, the magazine El malpensante (The Evil-Minded) came out with a more Colombian and more extensive version of what I had prepared for Talk. I called it Solitude & Company, the name that at one point Garca Mrquez was going to give to a film production company he wanted to set up with some Colombian partners. With the same title I published another version in the edition of The Paris Review commemorating its fiftieth anniversary, which in turn was translated and published in Mexico by the magazine Nexos in its spring 2003 issue. Almost a decade went by before I decided, in March 2010, that it was time to listen to those tapes again and transform them into this book.

When I finished listening to them, though, I realized that what I had was not enough for a book. I needed to fill in gaps. Which is why I began a second round of interviews with those who I thought would provide context and chronology to the first voices.

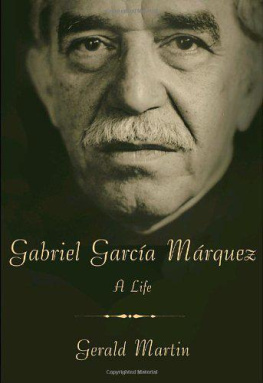

Solitude & Company is divided into two parts. In the first, B.C.: Before Cien aos de soledad, his siblings speak, as well as those who were his buddies before he became the universally loved Latin American icon. Those who knew him when he still didnt have a proper English tailor nor an English biographertwo things I heard him say are the marks of a writers successand didnt accompany presidents and multimillionaires (as on the night I saw him cut the baby-blue inaugural ribbon at the Museo Soumaya, Carlos Slims gift to Mexico City, which reminded me of the interviews I had prepared for Talk). This first part gathers together the voices of those irreverent and hopeful times when a boy from the provinces decided to become a writer. This is the story of how he did it. Here we witness the formation of the creator venerated throughout the world. In the second part, A.C.: After Cien aos de soledad, a prize-winning Garca Mrquez appears, a celebrated man.

A great deal has been written about Garca Mrquez, but no matter how much is written, the authors prose, the censorship of his memories, and the analysis of his biographer weigh heavily. Oral history, the formal name of this genre, allows those who were very close to him to describe for us the man who became the most important writer in Latin America, the lover of power, and defender to the end of Fidel Castro. It allows them to tell us how they welcomed him, helped him, and watched him create himself; it permits them to make us feel how much they love him or how much he annoyed them; just them, without other narrators or descriptions as intermediaries.

This book, then, is a ticket to a celebration where everybody talks, everybody shouts, everybody has an opinion and even tells lies. That is the essence of oral history, along the lines of Edie: American Girl by Jean Stein and George Plimpton, and Truman Capote: In Which Various Friends, Enemies, Acquaintances and Detractors Recall His Tur-bulent Career by Plimpton. This format, which fell from the skies with that imperative phone call from Tina Brown, is formidable because it is amusing and light, yet profoundly true.