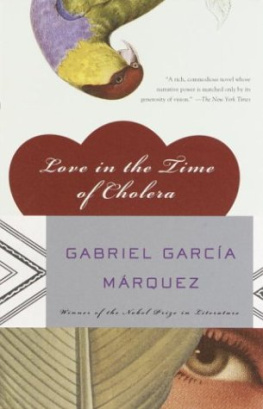

First Vintage International Edition, March 1989

Copyright 1986 by Alfred A. Knopf, Inc.

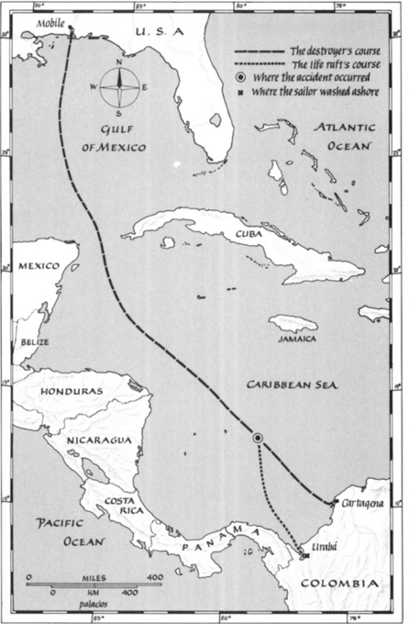

Map Copyright 1986 by Rafael Palacios

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Random House, Inc., New York, and in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

Originally published in Spain as Relato de un nufrago by Tusquets Editores, Barcelona.

Copyright 1955, 1970 by Gabriel Garca Mrquez.

This translation was originally published, in hardcover, by Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. in 1986.

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Garca Mrquez, Gabriel, 1928

The story of a shipwrecked sailor. Translation of: Relato de un nufrago. (Vintage International)

Reprint. Originally published: New York: Knopf, 1986.

1. Velasco, Luis Alejandro. 2. Survival (after airplane accidents, shipwrecks, etc.) I. Title. [G530. V442G3713 1987] 910.091636 86-46175

ISBN 0-679-72205-x (pbk.)

eBook ISBN: 978-1-101-91109-9

Cover design by John Gall

Cover art courtesy of Mary Evans Picture Library, London

v3.1

Contents

The Story of This Story

February 28, 1955, brought news that eight crew members of the destroyer Caldas, of the Colombian Navy, had fallen overboard and disappeared during a storm in the Caribbean Sea. The ship was traveling from Mobile, Alabama, in the United States, where it had docked for repairs, to the Colombian port of Cartagena, where it arrived two hours after the tragedy. A search for the seamen began immediately, with the cooperation of the U.S. Panama Canal Authority, which performs such functions as military control and other humanitarian deeds in the southern Caribbean. After four days, the search was abandoned and the lost sailors were officially declared dead. A week later, however, one of them turned up half dead on a deserted beach in northern Colombia, having survived ten days without food or water on a drifting life raft. His name was Luis Alejandro Velasco. This book is a journalistic reconstruction of what he told me, as it was published one month after the disaster in the Bogot daily El Espectador.

What neither the sailor nor I knew when we tried to reconstruct his adventure minute by minute was that our exhaustive digging would lead us to a new adventure that caused a certain stir in the nation and cost him his honor, and could have cost me my skin. At that time Colombia was under the military and social dictatorship of General Gustavo Rojas Pinilla, whose two most memorable feats were the killing of students in the center of the capital when the Army broke up a peaceful demonstration with bullets, and the assassination by the secret police of an undetermined number of Sunday bullfight fans who had booed the dictators daughter at the bullring. The press was censored, and the daily problem for opposition newspapers was finding politically germ-free stories with which to entertain their readers. At El Espectador, those in charge of that estimable confectionary work were Guillermo Cano, director; Jos Salgar, editor-in-chief, and I, staff reporter. None of us was over thirty.

When Luis Alejandro Velasco showed up of his own accord to ask how much we would pay him for his story, we took it for what it was: a rehash. The armed forces had sequestered him for several weeks in a naval hospital, and he had been allowed to talk only with reporters favorable to the regime and with one opposition journalist who had disguised himself as a doctor. His story had been told piecemeal many times, had been pawed over and perverted, and readers seemed fed up with a hero who had rented himself out to advertise watches (because his watch hadnt even slowed down during the storm); who appeared in shoe advertisements (because his shoes were so sturdy that he hadnt been able to tear them apart to eat them); and who had performed many other publicity stunts. He had been decorated, he had made patriotic speeches on radio, he had been displayed on television as an example to future generations, and he had toured the country amid bouquets and fanfares, signing autographs and being kissed by beauty queens. He had amassed a small fortune. If he was now coming to us without our having invited him, after we had tried so hard to reach him earlier, it was likely that he no longer had much to tell, that he was capable of inventing anything for money, and that the government had very clearly defined the limits of what he could say. We sent him away. But on a hunch, Guillermo Cano caught up with him on the stairway, accepted the deal, and placed him in my hands. It was as if he had given me a time bomb.

My first surprise was that this solidly built twenty-year-old, who looked more like a trumpet player than a national hero, had an exceptional instinct for the art of narrative, an astonishing memory and ability to synthesize, and enough uncultivated dignity to be able to laugh at his own heroism. In twenty daily sessions, each lasting six hours, during which I took notes and sprang trick questions on him to expose contradictions, we put together an accurate and concise account of his ten days at sea. It was so detailed and so exciting that my only concern was finding readers who would believe it. Not solely for that reason but also because it seemed fitting, we agreed that the story would be written in the first person and signed by him. This is the first time my name has appeared in connection with the text.