Gabriel Garcia Marquez - One Hundred Years of Solitude

Here you can read online Gabriel Garcia Marquez - One Hundred Years of Solitude full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2003, publisher: HarperCollins, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

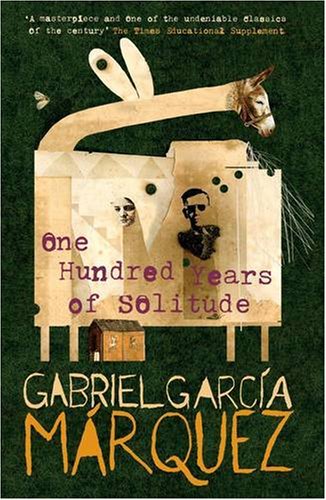

- Book:One Hundred Years of Solitude

- Author:

- Publisher:HarperCollins

- Genre:

- Year:2003

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

One Hundred Years of Solitude: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "One Hundred Years of Solitude" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Gabriel Garcia Marquez: author's other books

Who wrote One Hundred Years of Solitude? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

One Hundred Years of Solitude — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "One Hundred Years of Solitude" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

|

Gabriel Garca Mrquez

One Hundred Years of Solitude

1967

One of the most influential literary works of our time, One Hundred Years of Solitude is a dazzling and original achievement by the masterful Gabriel Garca Mrquez, winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature.

One Hundred Years of Solitude tells the story of the rise and fall, birth and death of the mythical town of Macondo through the history of the Buenda family. Inventive, amusing, magnetic, sad, and alive with unforgettable men and womenbrimming with truth, compassion, and a lyrical magic that strikes the soulthis novel is a masterpiece in the art of fiction.

M ANY YEARS LATER as he faced the firing squad, Colonel Aureliano Buenda was to remember that distant afternoon when his father took him to discover ice. At that time Macondo was a village of twenty adobe houses, built on the bank of a river of clear water that ran along a bed of polished stones, which were white and enormous, like prehistoric eggs. The world was so recent that many things lacked names, and in order to indicate them it was necessary to point. Every year during the month of March a family of ragged gypsies would set up their tents near the village, and with a great uproar of pipes and kettledrums they would display new inventions. First they brought the magnet. A heavy gypsy with an untamed beard and sparrow hands, who introduced himself as Melquades, put on a bold public demonstration of what he himself called the eighth wonder of the learned alchemists of Macedonia. He went from house to house dragging two metal ingots and everybody was amazed to see pots, pans, tongs, and braziers tumble down from their places and beams creak from the desperation of nails and screws trying to emerge, and even objects that had been lost for a long time appeared from where they had been searched for most and went dragging along in turbulent confusion behind Melquades magical irons. Things have a life of their own, the gypsy proclaimed with a harsh accent. Its simply a matter of waking up their souls. Jos Arcadio Buenda, whose unbridled imagination always went beyond the genius of nature and even beyond miracles and magic, thought that it would be possible to make use of that useless invention to extract gold from the bowels of the earth. Melquades, who was an honest man, warned him: It wont work for that. But Jos Arcadio Buenda at that time did not believe in the honesty of gypsies, so he traded his mule and a pair of goats for the two magnetized ingots. rsula Iguarn, his wife, who relied on those animals to increase their poor domestic holdings, was unable to dissuade him. Very soon well have gold enough and more to pave the floors of the house, her husband replied. For several months he worked hard to demonstrate the truth of his idea. He explored every inch of the region, even the riverbed, dragging the two iron ingots along and reciting Melquades incantation aloud. The only thing he succeeded in doing was to unearth a suit of fifteenth-century armor which had all of its pieces soldered together with rust and inside of which there was the hollow resonance of an enormous stone-filled gourd. When Jos Arcadio Buenda and the four men of his expedition managed to take the armor apart, they found inside a calcified skeleton with a copper locket containing a womans hair around its neck.

In March the gypsies returned. This time they brought a telescope and a magnifying glass the size of a drum, which they exhibited as the latest discovery of the Jews of Amsterdam. They placed a gypsy woman at one end of the village and set up the telescope at the entrance to the tent. For the price of five reales, people could look into the telescope and see the gypsy woman an arms length away. Science has eliminated distance, Melquades proclaimed. In a short time, man will be able to see what is happening in any place in the world without leaving his own house. A burning noonday sun brought out a startling demonstration with the gigantic magnifying glass: they put a pile of dry hay in the middle of the street and set it on fire by concentrating the suns rays. Jos Arcadio Buenda, who had still not been consoled for the failure of big magnets, conceived the idea of using that invention as a weapon of war. Again Melquades tried to dissuade him, but he finally accepted the two magnetized ingots and three colonial coins in exchange for the magnifying glass. rsula wept in consternation. That money was from a chest of gold coins that her father had put together ova an entire life of privation and that she had buried underneath her bed in hopes of a proper occasion to make use of it. Jos Arcadio Buenda made no attempt to console her, completely absorbed in his tactical experiments with the abnegation of a scientist and even at the risk of his own life. In an attempt to show the effects of the glass on enemy troops, he exposed himself to the concentration of the suns rays and suffered burns which turned into sores that took a long time to heal. Over the protests of his wife, who was alarmed at such a dangerous invention, at one point he was ready to set the house on fire. He would spend hours on end in his room, calculating the strategic possibilities of his novel weapon until he succeeded in putting together a manual of startling instructional clarity and an irresistible power of conviction. He sent it to the government, accompanied by numerous descriptions of his experiments and several pages of explanatory sketches; by a messenger who crossed the mountains, got lost in measureless swamps, forded stormy rivers, and was on the point of perishing under the lash of despair, plague, and wild beasts until he found a route that joined the one used by the mules that carried the mail. In spite of the fact that a trip to the capital was little less than impossible at that time, Jos Arcadio Buenda promised to undertake it as soon as the government ordered him to so that he could put on some practical demonstrations of his invention for the military authorities and could train them himself in the complicated art of solar war. For several years he waited for an answer. Finally, tired of waiting, he bemoaned to Melquades the failure of his project and the gypsy then gave him a convincing proof of his honesty: he gave him back the doubloons in exchange for the magnifying glass, and he left him in addition some Portuguese maps and several instruments of navigation. In his own handwriting he set down a concise synthesis of the studies by Monk Hermann, which he left Jos Arcadio so that he would be able to make use of the astrolabe, the compass, and the sextant. Jos Arcadio Buenda spent the long months of the rainy season shut up in a small room that he had built in the rear of the house so that no one would disturb his experiments. Having completely abandoned his domestic obligations, he spent entire nights in the courtyard watching the course of the stars and he almost contracted sunstroke from trying to establish an exact method to ascertain noon. When he became an expert in the use and manipulation of his instruments, he conceived a notion of space that allowed him to navigate across unknown seas, to visit uninhabited territories, and to establish relations with splendid beings without having to leave his study. That was the period in which he acquired the habit of talking to himself, of walking through the house without paying attention to anyone, as rsula and the children broke their backs in the garden, growing banana and caladium, cassava and yams, ahuyama roots and eggplants. Suddenly, without warning, his feverish activity was interrupted and was replaced by a kind of fascination. He spent several days as if he were bewitched, softly repeating to himself a string of fearful conjectures without giving credit to his own understanding. Finally, one Tuesday in December, at lunchtime, all at once he released the whole weight of his torment. The children would remember for the rest of their lives the august solemnity with which their father, devastated by his prolonged vigil and by the wrath of his imagination, revealed his discovery to them:

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «One Hundred Years of Solitude»

Look at similar books to One Hundred Years of Solitude. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book One Hundred Years of Solitude and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.