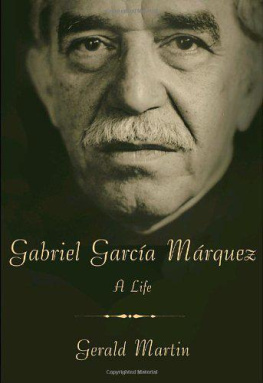

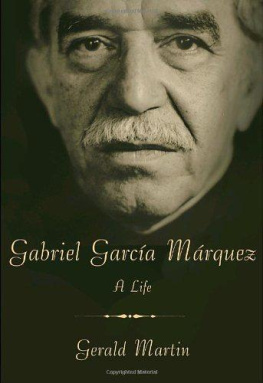

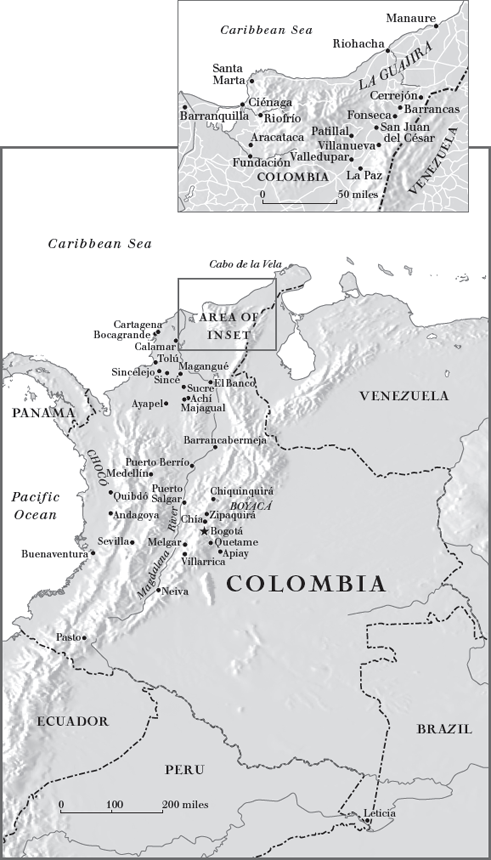

Gabriel Garca Mrquez was born in Aracataca, Colombia, in 1927. He studied at the University of Bogot and later worked as a reporter for the Colombian newspaper El Espectador and as a foreign correspondent in Rome, Paris, Barcelona, Caracas and New York. He is the author of several novels and collections of stories, including Eyes of a Blue Dog (1947), Leaf Storm (1955), No One Writes to the Colonel (1958), In Evil Hour (1962), Big Mamas Funeral (1962), One Hundred Years of Solitude (1967), Innocent Erndira and Other Stories (1972), The Autumn of the Patriarch (1975), Chronicle of a Death Foretold (1981), Love in the Time of Cholera (1985), The General in His Labyrinth (1989), Strange Pilgrims (1992), Of Love and Other Demons (1994) and Memories of My Melancholy Whores (2005). Many of his books are published by Penguin. Gabriel Garca Mrquez was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1982. He lives in Mexico City.

1

M Y MOTHER ASKED ME to go with her to sell the house. She had come that morning from the distant town where the family lived, and she had no idea how to find me. She asked around among acquaintances and was told to look for me at the Librera Mundo, or in the nearby cafs, where I went twice a day to talk with my writer friends. The one who told her this warned her: Be careful, because theyre all out of their minds. She arrived at twelve sharp. With her light step she made her way among the tables of books on display, stopped in front of me, looking into my eyes with the mischievous smile of her better days, and before I could react she said:

Im your mother.

Something in her had changed, and this kept me from recognizing her at first glance. She was forty-five. Adding up her eleven births, she had spent almost ten years pregnant and at least another ten nursing her children. She had gone gray before her time, her eyes seemed larger and more startled behind her first bifocals, and she wore strict, somber mourning for the death of her mother, but she still preserved the Roman beauty of her wedding portrait, dignified now by an autumnal air. Before anything else, even before she embraced me, she said in her customary, ceremonial way:

Ive come to ask you to please go with me to sell the house.

She did not have to tell me which one, or where, because for us only one existed in the world: my grandparents old house in Aracataca, where Id had the good fortune to be born, and where I had not lived again after the age of eight. I had just dropped out of the faculty of law after six semesters devoted almost entirely to reading whatever I could get my hands on, and reciting from memory the unrepeatable poetry of the Spanish Golden Age. I already had read, in translation, and in borrowed editions, all the books I would have needed to learn the novelists craft, and had published six stories in newspaper supplements, winning the enthusiasm of my friends and the attention of a few critics. The following month I would turn twenty-three, I had passed the age of military service and was a veteran of two bouts of gonorrhea, and every day I smoked, with no foreboding, sixty cigarettes made from the most barbaric tobacco. I divided my leisure between Barranquilla and Cartagena de Indias, on Colombias Caribbean coast, living like a king on what I was paid for my daily commentaries in the newspaper El Heraldo, which amounted to almost less than nothing, and sleeping in the best company possible wherever I happened to be at night. As if the uncertainty of my aspirations and the chaos of my life were not enough, a group of inseparable friends and I were preparing to publish without funds a bold magazine that Alfonso Fuenmayor had been planning for the past three years. What more could anyone desire?

For reasons of poverty rather than taste, I anticipated what would be the style in twenty years time: untrimmed mustache, tousled hair, jeans, flowered shirts, and a pilgrims sandals. In a darkened movie theater, not knowing I was nearby, a girl I knew told someone: Poor Gabito is a lost cause. Which meant that when my mother asked me to go with her to sell the house, there was nothing to prevent me from saying I would. She told me she did not have enough money, and out of pride I said I would pay my own expenses.

At the newspaper where I worked, this was impossible to arrange. They paid me three pesos for a daily commentary and four for an editorial when one of the staff writers was out, but it was barely enough to live on. I tried to borrow money, but the manager reminded me that I already owed more than fifty pesos. That afternoon I was guilty of an abuse that none of my friends would have been capable of committing. At the door of the Caf Colombia, next to the bookstore, I approached Don Ramn Vinyes, the old Catalan teacher and bookseller, and asked for a loan of ten pesos. He had only six.

Neither my mother nor I, of course, could even have imagined that this simple two-day trip would be so decisive that the longest and most diligent of lives would not be enough for me to finish recounting it. Now, with more than seventy-five years behind me, I know it was the most important of all the decisions I had to make in my career as a writer. That is to say: in my entire life.