Thank you for downloading this Simon & Schuster eBook.

Join our mailing list and get updates on new releases, deals, bonus content and other great books from Simon & Schuster.

C LICK H ERE T O S IGN U P

or visit us online to sign up at

eBookNews.SimonandSchuster.com

C ONTENTS

For my mother and father

My story gets told in various ways: a romance, a dirty joke, a war, a vacancy.

J ALALUDDIN R UMI

A UTHORS N OTE

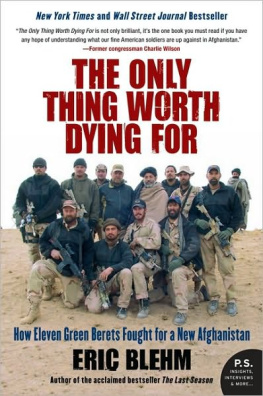

T his book is based on hundreds of interviews and court, government, and military documents, some obtained under the Freedom of Information Act. I have also drawn on my experience as a reporter in Afghanistan from 2002 to 2004 and during six return trips, several more than a month long, between 2007 and 2010. Much of the recorded speech comes from notes and interview transcripts or from scenes I witnessed, and is marked by double quotes (...). Where I have reconstructed scenes based on documents and participants recollections, dialogue appears in single quotes (...). In the interest of maintaining narrative flow, I have sought to minimize complex attribution in the body of the text. Readers can learn more about sources in the Notes section.

P ROLOGUE

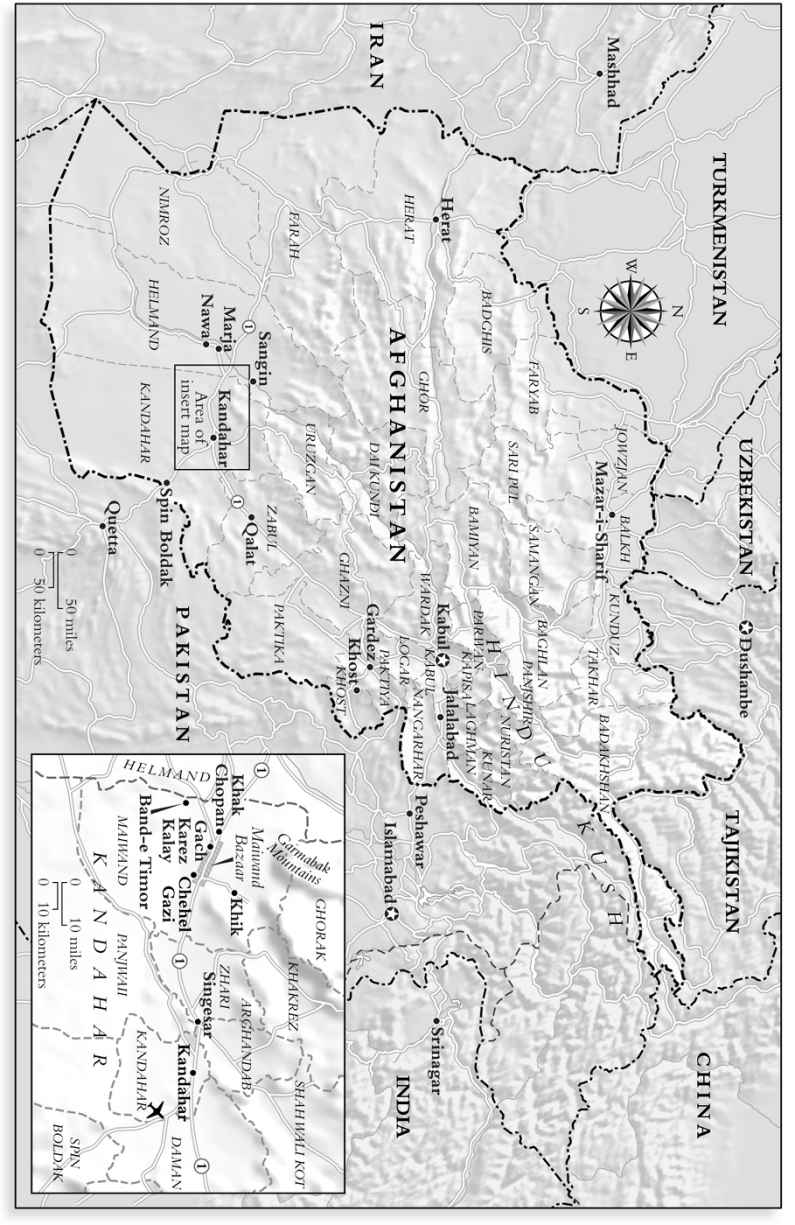

S ometimes the events of a single day tell the story of a war. On November 4, 2008, voters in the United States elected Barack Obama president, laying the groundwork for an expanded counterinsurgency campaign in Afghanistan. On the same day, in the tawny flatlands west of Kandahar, a group of American civilians and soldiers set out on a hopeful mission that would change their lives and those of the Afghans they met forever. Among them was a brave and gentle woman with a Wellesley degree, a soldiers devotion to her country, and a fierce curiosity about the world. Theirs was an anthropological undertaking, matching the audacity of Obama, an anthropologists son.

This book tells the story of what happened that day, and of the conception and rapid early growth of the Human Terrain System, a central tool in what was supposed to be a more culturally conscious way of war. It traces the first four years of this experiment, from its beginnings as a cultural knowledge database to fight homemade bombs in Iraq through its multimillion-dollar expansion. It follows the program through the height of American involvement in Afghanistan in 2010, when one hundred thousand U.S. troops were stationed there along with more than twenty Human Terrain Teams. For much of this period, the projects senior social scientist was an anthropologist-cum-war-theorist raised in a radical squatters community in Marin County, California, and educated at Ivy League schools. She would become the most flamboyant evangelist for an evolving form of battlefield information known as cultural intelligence. Its director was a scrappy and unconventional career soldier who believed the Army could be cured of its ethnocentrism, and that this goal justified almost any means taken to achieve it. Yet he himself embodied a profoundly American worldview: that every problem has a solution, and that Americans can find it.

The Human Terrain System was born in the shadows of a revolution within an Army that had tried to bury the painful lessons of Vietnam. In Iraq and Afghanistan, soldiers revived the low-tech practices of counterinsurgency, emphasizing the value of human contact for intelligence gathering, political persuasion, and targeted killing. The Human Terrain System was the Armys most ambitious attempt in three decades to bring social science knowledge to the battlefield, but it was unwelcome to some American anthropologists, who believed their discipline had too often been hijacked for imperialist ends. They were right, but so was the Army.

In Afghanistan, context makes intelligence make sense. American soldiers could not possibly know where to build a school or vet tips about who was the enemy without knowing which tribe their informant belonged to, who his rivals and relatives were, where he lived, how he had come to live there, and a thousand other details that anthropologists or journalists might collect but that soldiers rarely thought to ask about. Yet here lay a difficulty. Cultural understanding was a tool that could be used for saving or for killing, like the knife that cuts one way in the hands of a surgeon and another in the grip of a murderer. The Human Terrain System wasnt designed to tell the military who to kill. But a child could see that who to kill and who to save were questions that answered each other.

There are two kinds of military cultural knowledge. The first kind gives rise to directives that soldiers in Afghanistan should avoid showing the soles of their feet; that they should use only their right hands for eating; that they should accept tea when it is offered; and that men should refrain from searching women. The other kind of cultural knowledge, sometimes known as cultural intelligence, is what the military needs to make smart decisions about which local leaders to support, who to do business with, where to dig wells and build clinics, who to detain and kill, and when to disengage. Cultural intelligence is the textured sense of a place that helps soldiers understand how tribal systems work; how criminals, drug dealers, and militants are connected; the role of marriage in cementing business relationships and political alliances; and the way money and power move between families and villages. It was important for soldiers to understand Afghan culture so they wouldnt needlessly offend people. But for a force with a mission to strengthen local government and kill and capture terrorists in a place with no working justice mechanisms, it was crucial, too, that Americans make informed decisions about who to protect, which lives to ruin, and which lives to take. They routinely didnt.

The Human Terrain System was developed to help address these problems. What follows is the story of a hopeful moment when America, in the midst of two wars, sought to change the way it fights, and of a remarkable woman and her teammates, who risked everything to save the Army from itself.

1. E LECTION D AY

November 4, 2008

I n the desert west of Kandahar, the nights were dark and chilly and the stars looked close enough to touch. At midday, the summer sun could kill you, but it was fall now, the dry air smelling of hay and woodsmoke. The Americans had landed three months earlier. They ate precooked food, used portable toilets, and slept in green canvas tents in a gravel lot behind walls that some soldiers judged too low to stop an inventive attacker. Stray cats rubbed up against their legs.

One morning that November, a platoon of soldiers from the 2nd Battalion, 2nd Regiment of the Armys 1st Infantry Division left the base on foot. The autumn sky was clear and bright, and the soldiers thought their mission would be an easy one. As some of the first Americans to patrol Maiwand District, a sandy stretch of farmland deep in the Afghan south, the Third Platoon of Comanche Company was building a detailed map of the settlements at the heart of the area, where most of Maiwands people lived. On this day they would be photographing the northern quadrant of Chehel Gazi, a village that began about five hundred yards outside the walls of their base.

Three civilians joined the patrol that day. They were part of an experimental Army project called the Human Terrain System, which was designed to help soldiers understand local culture. Before leaving the base, they stood together in a tight circle, holding hands, heads bowed, as they did before every mission.