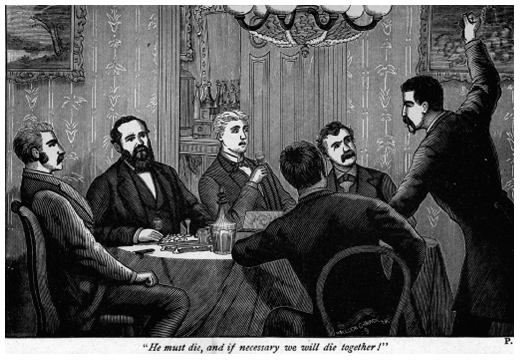

Frontispiece: Suspected Baltimore plotter Cypriano Ferrandini urging his views while undercover agent Allan Pinkerton (with beard) listens. (The Spy of the Rebellion)

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review.

Many years ago, my grandfather, Wesley Seitz Watson, gave me his most cherished possession, Carl Sandburg's Abraham Lincoln: The War Years, which eventually started me on this journey. This book is in loving memory of him.

PREFACE

CONSPIRACY. A combination or confederacy between two or more persons formed for the purpose of committing by their joint efforts, some unlawful or criminal act.

Black's Law Dictionary

THIS IS THE STORY OF WHAT HAS BECOME popularly known as the Baltimore Plot. It is a thrilling story, pieced together from literally thousands of bits of evidence, informed by the letters, diaries, testimony, contemporary newspaper accounts, and other records of eyewitnesses to the events described. These scattered clues, never before tied together to tell the complete tale, have been sifted and arranged, as a lawyer might do in presenting a case to the jury. In this instance, the crime charged is that of conspiracy to assassinate Abraham Lincoln in February 1861.

A word of caution: Those expecting to find a smoking gun in the hands of one of the suspects will be disappointed; no such conclusive proof exists. There is no written agreement among the alleged conspirators, no signed confession. With the exception of the few shadowy characters identified and quoted in the reports of Allan Pinkerton's operatives, none of the alleged conspirators is known to have ever admitted their role in plotting to kill Abraham Lincoln in Baltimore in February 1861. Indeed, no one was ever even charged with the crime.

Our proof, therefore, depends largely on circumstantial evidence, of gluing together what we know with the logical inferences we might draw by examining the alleged conspirators's own words, their habits, their known prejudices, their relationships with other suspected conspirators, and other evidence of wrongdoing tending to show a common scheme. If this book succeeds in convincing the reader that the plot was more than a fanciful rumor, then I have done my job.

Lawyers go to trial with the case they have. It is never as good as the case they wish they had. The available evidence is nearly always incomplete. It isalmost never the best evidence. Evidence, other than forensic, comes in two primary forms, both suspect: witnesses and documents. Our case depends on both of these.

Witnesses forget. Memories fade. Being mere mortals, witnesses, like writers, get it wrong, often innocently. Sometimes they lie, even under oath. Within the veins of all people, whether lay witness, expert, or the accused, flow the serums of anti-truthself-interest, bias, and personal grudges.

The contents of documents are tempting to take as gospel. This is generally a mistake, particularly for newspaper accounts, often sensational stories hurriedly dashed off on the telegraph wires before facts are verified. Some documents, of course, are lost forever or destroyed by those intent on eradicating whatever evidence they contain. Some are illegible. Some are forged. Some, like the witnesses who wrote them, simply record lies or shades of truth colored to the writer's liking.

The same shortcomings are true of the evidence presented here. Worse, by trial standards, it is ancient evidenceover 150 years old for documents recorded at the timeor written years, even decades, after the fact. Because we have no living witnesses, ours is evidence that can be neither tempered if true, nor torched if false, in the fire of cross-examination.

And yet, ours is good evidence, insofar as there is a great volume of it, and much of it is corroborated. Our best evidence was recorded contemporaneously with the events described in the writings of well-informed persons and seemingly credible eyewitnesses. It is evidence written at a time in history when, for the most part, people took pride in what they wrote, wrote well, and verified their facts. They tended, in this author's view, to sign their names to what they wrote with solemnity, as though under oath, to a greater extent than exists today.

It is with this evidence that we hope to better inform, if not conclusively answer, the question of whether or not there was a conspiracy to assassinate President-elect Lincoln in February 1861the Baltimore Plot.

The people present during the events described here are our witnesses. Their writings are their testimony. The guiding light of historians serves as our rule of law and voice of reason. You are the judge and the jury. Let the evidence speak for itself, and be decided upon fairly.

CHAPTER ONE

MOTIVE, MEANS, AND OPPORTUNITY

Human action can be modified to some extent, but human nature cannot be changed.Abraham Lincoln, Cooper Union Address, February 27, 1860

IN FEBRUARY 1861, AMERICA WAS DYING. To many, Abraham Lincoln, not slavery, was the cause. A man with virtually no administrative experience, Lincoln had won the presidential election the previous November by garnering a majority of the electoral vote, but less than half of the popular vote. In response, seven states in the Deep South seceded, and more threatened to do so. Also in response, many American cities, North and South, fearing civil war was now inevitable, slid into economic recession.

As if these problems weren't bad enough, Lincoln had another practical, yet very real problem. He needed to get from Springfield, Illinois, to Washington to be inaugurated on March 4. Before his political journey could begin, he had to complete a rail journey of over a thousand miles, cutting through the heart of an anxious America. And on this journey, Lincoln would learn, or at least be led to believe, that there existed in Baltimore a plot to murder him. The information would come from several trusted intelligence sources, including the well-known private detective from Chicago, Allan Pinkerton.

But was there, in February 1861, a conspiracy to assassinate President-elect Lincoln in Baltimore? If so, were secessionist members of President Buchanan's administration, the newly formed Washington Peace Conference, or Congressmen such as the fiery Texas senator Louis T. Wigfallor even Vice President Breckinridge involved? Might John Wilkes Booth, a Baltimore native, those he knew, Baltimore city officials, or Maryland's slaveholding governor, Thomas Holliday Hicks, have been complicit? Did Lincoln's suspicion ofa plot to murder him in Baltimore, whether or not such a plot existed, dictate his war strategy, his cabinet selections, the trust he placed in those around him, or his feelings toward Baltimore and Maryland early on in his administration?