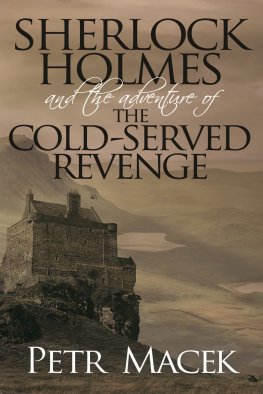

Holed up at Charing Cross during the Blitz in London, Frank Thomas discovered a battered tin dispatch box crammed with papers. Here were Dr. Watson's records of unpublished cases by the world-famous detective, Sherlock Holmes. After years of legal battles, Frank Thomas has now brought to light.

SHERLOCK HOLMES AND THE TREASURE TRAIN, adapted from the memoirs of John H. Watson, M.D.

Chapter 1

The Refusal

WHEN MY FRIEND Sherlock Holmes and I were finally ushered into the conference room of the Birmingham and Northern Railroad, I must have shown surprise. The building that housed the great transportation company shared the yellow-brick sameness of its neighbors in the Waterloo area. Its nerve center was, however, a far cry from early nineteenth-century architecture, being reminiscent of the great hall of an ancient feudal keep. Stucco walls soared better than two stories to a curved ceiling of stout timbers joined by cast-iron straps. The door to this impressive chamber was of carved oak. A massive fireplace into which I could have stepped without bending my head dominated one wall. Around it, flintlock muskets and swords of various ages hung vertically. In their midst, on a short staff, was a regimental banner, which I judged to be Russian, a captured memento of the Crimea. In front of the fireplace was a long trestle table flanked by benches. A large Jacobean armchair was positioned at each end. The oak gleamed of oil and the flickering light of burning logs threw dancing shadows on the table and adjacent artifacts. Twin lighting fixtures hung from chain hoists over each end of the table and provided the only modern touch to a scene that provoked an immediate impression of solidity and grandeur.

Under different circumstances I might have been prompted to pose questions regarding the many obviously authentic mementos that were the warp and woof of the room's character, as might Holmes, as he had indulged in a flirtation with medieval architecture at one time. However this was not to be, for things took a different turnand not one for the better, I should add.

The whole affair had gotten off to a bad start, beginning with the somewhat peremptory summons to the B & N building. At the time I had been surprised when the master sleuth abandoned our chambers at 221B Baker Street to come to the headquarters of the rail empire, though its president, Alvidon Daniel Chasseur, was a potential client of acknowledged solvency. Upon arrival at the formerly select residential neighborhood, now destroyed by the coming of the railways, we had been allowed to cool our heels in a drafty outer office while news of our arrival was relayed through a chain of command. Holmes, accustomed to being welcomed with red-carpet gratitude, adopted an imperious attitude toward the entire proceedings, which was not soothed by the manner of Mr. Chasseur or his board of directors, for such is what I judged the others seated at the table to be.

The rail tycoon, hunched in one of the armchairs, waved us toward a free space on the bench at his left while concluding some words with a grizzled man on his immediate right. Facing him, at the other end of the long table, was a fair and youngish-looking chap who had the grace to rise at our arrival. His face was clean-shaven and rugged. I judged him to be in his early thirties, which made him the youngest man in the room.

Having concluded his comments to his nearest employee, Chasseur now deigned to devote his attention to Holmes.

As he brushed back an errant wisp of white hair, the tycoon fastened large, rather myopic eyes on Holmes in an abrupt manner, which I was sure had struck terror in friends and adversaries as well on numerous occasions. Holmes, his face impassive, returned the stare without a flicker of emotion. The financier never so much as favored me with a glance. I was part of the furniture, as were his associates around the table, though he did single one out at this point.

"Mr. Holmes, we wish to discuss the matter of the gold shipment stolen from the Birmingham and Northern's special flyer but a short time ago. It was our security chief, Richard Ledger, who brought your name to my attention."

A flick of a bony forefinger indicated the youngish man I had noted at the other end of the table. Chasseur paused as though expecting an expression of gratitude from Holmes and, when none was forthcoming, continued, his voice dry and rather grating.

"My first impulse was to enlist the aid of the world's foremost detective, Monsieur Alphonse Bertillon, since the French have some involvement in this matter. My second thought was one of our Scotland Yard inspectors, like Lestrade, who do involve themselves in problems other than their official activities on occasion."

Chasseur again paused to allow the fact to sink in that Sherlock Holmes was but a third choice foisted on him. I took the moment to bid an adieu to the matter of the B & N Railroad. This despite the fact that we had not been involved in a profitable case for some time. Neither the pursuit of the Golden Bird nor the adventure involving the Sacred Sword had resulted in a fee, while incurring considerable expense. However, Chasseur had effectively shunted my friend from the gold robbery and he might better have been occupied waving a red flag in a bullring in Toledo. Had we been in some earlier time, when men were prone to vent their spleen with violent action, I could easily picture Holmes tearing one of the swords from the wall and carving Chasseur up like a Christmas goose. Instead, he placidly viewed the aged financier. The silence became nerve-racking and those around the table stirred uneasily. Finally Chasseur had to give in to the mood of the moment and added to his comments, though in a slightly more conciliatory tone.

"Ledger has considerable faith in your ability, Mr. Holmes. He was formerly with the army of India and is the finest big-game hunter in the world."

By this time, I was as nervous as a cat and denied, with effort, the impulse to cross my legs or make some movement that would relieve the tenseness that had crept, nay galloped, into the scene. To my relief, Holmes finally contributed to the conversation, and in an even tone of voice, which must have cost him dearly.

"It has been said that one should follow first impulses, and relative to that, I shall make some mention of matters which might prove helpful. Gratis, of course."

Unable to divine the direction of the wind, the financier was now gazing at Holmes with the first shadow of surprise infiltrating his large eyes.

"The esteemed Bertillon's forte is identification based on his Bertillonage system. He is not an 'in the field' operative. Lestrade is no doubt already involved in your affair since he seems to have a way of getting assigned to the most newsworthy cases. If you consider additional Scotland Yard assistance, you might think of Hopkins or Gregson or Alec MacDonald, who gives evidence of becoming the best of the lot. I know of all their work, being a consulting detective."

"I am not familiar with that title," said Chasseur quickly.

"No surprise since I am the only one in the world. A consulting detective has his services solicited by other professionals when they arrive at dead ends. I have but recently solved a little matter for Francis le Villard, a compatriot of Bertillon. A matter, I might add, which the Sret Nationale was completely incapable of dealing with."

Chasseur made as though to comment, but Holmes was in full stride now and I relaxed, somewhat gleefully, anticipating the chips to fall from the tycoon's oak under the blows of Holmes' verbal ax.

Next page