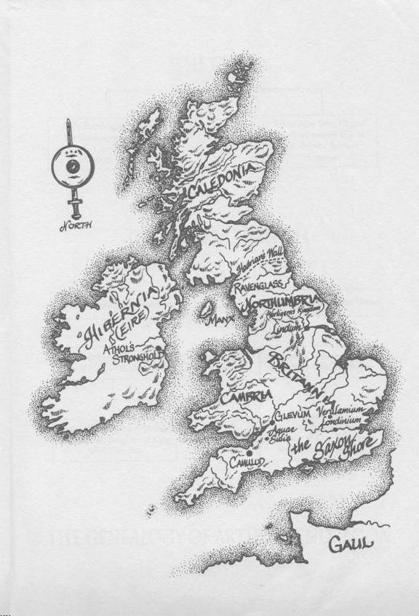

THE SAXON SHORE

THE CAMULOD CHRONICLES

JACK WHYTE

To my wife, Beverley,

with gratitude for twenty-five years of long-suffering patience, support and encouragement.

THE LEGEND OF THE SKYSTONE

Out of the night sky there will fall a stone

That hides a maiden born of murky deeps,

A maid whose fire-fed, female mysteries

Shall give life to a lambent, gleaming blade,

A blazing, shining sword whose potency

Breeds warriors. More than that,

This weapon will contain a woman's wiles

And draw dire deeds of men; shall name an age;

Shall crown a king, called of a mountain clan

Who dream of being drawn from dragon's seed;

Fell, forceful men, heroic, proud and strong,

With greatness in their souls.

This king, this monarch, mighty beyond ken,

Fashioned of glory, singing a song of swords,

Misting with magic madness mortal men,

Shall sire a legend, yet leave none to lead

His host to triumph after he be lost.

But death shall ne'er demean his destiny who,

Dying not, shall ever live and wait to be recalled.

PROLOGUE

There is a traditional belief, seldom spoken of but widely held, that age brings wisdom, and that wisdom, once achieved through some arcane epiphany, continues to grow inexorably with increasing age. like most people, I accepted that throughout my life, until the day I round that I had somehow grown old enough to be considered wise by others. The discovery frightened me badly and shook my faith in most of my other beliefs.

Now that I have survived everyone I once knew, I grow more aware each day of how unwise I have been throughout my life. Unwise might even be too mild a word for this folly of persistence I betray in clinging to a life of solitude and pain. The pain is unimportant, and in a total absence of sympathy it has become a form of penance I gladly accept and endure in expiation of my sins of omission and unpreparedness. The solitude, however, grows unbearable at times and I am now accustomed to talking to myself merely to hear the sound of a human voice. Sometimes I argue with myself. Sometimes I read aloud what I have written. Sometimes I speak my unformed thoughts, shaping them audibly to light a beacon in the darkness in my efforts to write down a clean, coherent chronicle of what once flourished proudly in this land but has now ceased to be.

I find it strange nowadays to think that I may be the only one alive in all this land who knows how to write words down, and because of that may be the only one who knows that words, unwritten, have no value. Set down in writing, words are real; legible, memorable, exact and permitting recollection, imaginings and wonder. Otherwise, sung or spoken, whispered to oneself or shouted to the winds, words are ephemeral, perishing as they are uttered. That, at least, I have learned in my extreme age.

And so I write my chronicle, and in the writing of it I maintain the life in my old bones, unable to consider death while yet the task remains unfinished. For I believe this story must survive. Empires have risen in this world and fallen, and history takes note of few of them. Those that survive in the memories of men do so by virtue of the faults that flawed their greatness. But here in Britain, in my own lifetime, a spark ignited in the breast of one strong man and became a clean, pure flame to light the world, a beacon that might have outshone the great lighthouse of Pharos, had a sudden gust of willful wind not extinguished it prematurely. In the space of a few, bright years, something new stirred in this land; something unprecedented; something wonderful; and men, being men, perceived it with stunned awe and then, being men, destroyed it without thought, for being new and strange.

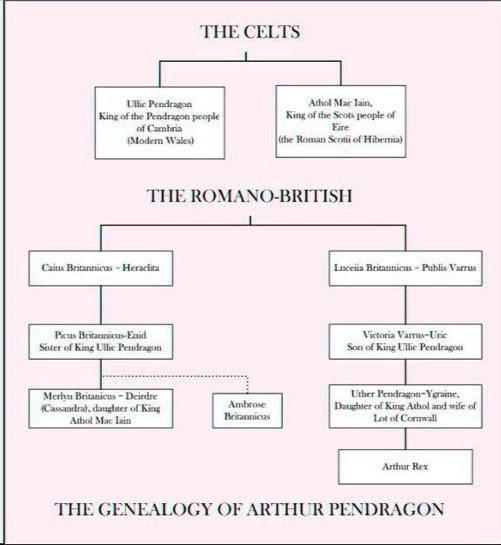

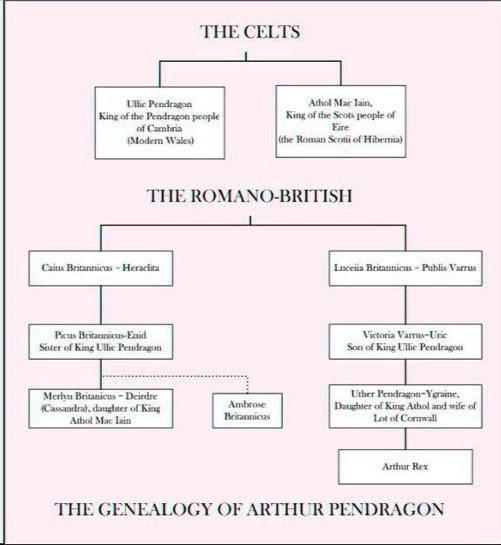

When it was over, when the light was snuffed out like a candle flame, a young man, full of hurt and bewilderment, asked me to explain how everything had happened. He expected me to know, for I was Merlyn, the Sorcerer, Fount of all Wisdom. And in my folly, feeling for the youth, I sought to tell him. But I was too young, at sixty-four, to understand what had occurred and why it had been inevitable. That was a decade and a half ago. Even now, after years of solitary thought and questioning, I only know that, at the start of Arthur's life, I had no thought of being who I am today, nor of how I could presume to teach a child to be the man, the King, the potent Champion he would become. In those years, I had far too much to learn, myself, to have had time for thoughts on teaching.

I know that by the rules of random chance Arthur should never have been born, but was; and then, being born, he should have died in infancy, yet lived. Feared and despised by men who had no knowledge of his nature, he should not have survived his early boyhood, yet escaped to grow. I know that, reared by men who scarcely knew the name or the meaning of kingship, he should never have emerged to be the High King he became, the culmination of a dream dreamed long before, by men dead long before his birth. I know he was my challenge and my pride, my pupil and my life's sole, crowned success. And I know the dream he fostered and made real deserves to live forever; hence this task of mine.

I

I could not identify the clattering noise that woke me, and for a space of heartbeats I lay befuddled, not knowing where I was. The sun was high and hot, and I felt my bed tilt alarmingly. Then I became aware of the warmth of the tiny baby I held cradled in my arm, and I remembered everything.

We were adrift in a small galley or birney that was much too large for me to control alone, even had I known how. The smell of the bearskin pelt on which we lay mingled with the scents of sun-warmed pitch and timber. A heavy, rusted, three-pronged grappling hook had landed on the planking beside me, close to my head. As I focused on it, the thing leapt away from me again, before burying two of its points in the solid timbers of the boat's side. I rolled away from the child and struggled to my feet, throwing myself to the side of the boat and looking up and out.

Above me, towering over and dwarfing our small boat, was a great galley with a single, soaring mast and a rearing, giant, painted dragon's head at the prow. In my first glance I saw a row of long oars, glistening with water, raised vertically to permit the two craft to come together, then a red-bearded warrior standing on the prow behind the dragon's head, leaning backward against the pull as he drew in his rope, hand over hand, dragging my smaller craft towards him. Beside him, another man was in the act of throwing a second grappling hook, and I pulled my head down and out of sight as the metal head landed behind me and was jerked back to thump into the birney's timbers, lodging farther forward, beside the first. As I sprawled away to one side, a roar of surprise told me that my appearance had disconcerted them no less than theirs had me. A third and then a fourth hook clanked aboard and made themselves fast, and I felt our boat being hauled in like a fish, its motion changing as it struck laterally against the waves.

This time I raised my head cautiously and saw that it was the target for a score of bows, all of their arrows pointing at my eyes. I raised my hands high above my head, fingers spread, showing them I had no thought of fight or flight, and immediately slid back down the sloping side before stepping hastily back to the centre of the deck, my hands still high above my head as I fought to keep my footing, waiting for the first arrow to find me. Below me, the child had awakened and begun to howl with hunger, his tiny, angry protests lost amid the noises that now swelled all around us.

Next page