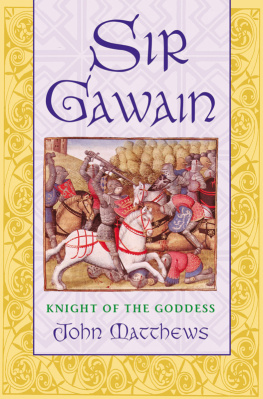

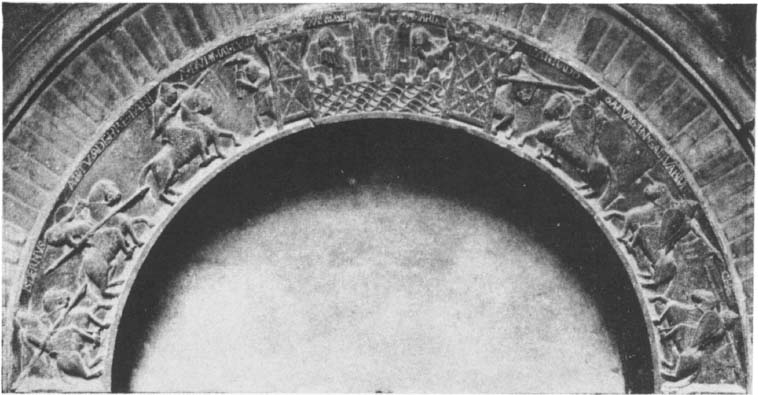

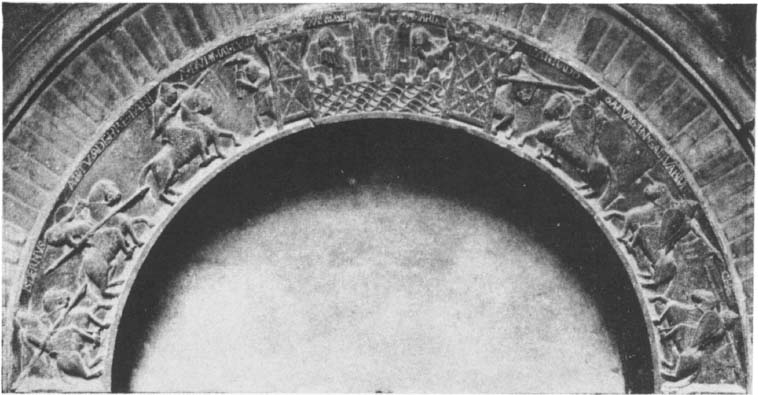

S CULPTURED A RCHIVOLT AT M ODENA C ATHEDRAL

Attack by Gawain and Arthur on Castle of Mar doc, Lord of Hades

Published in 1997 by

Academy Chicago Publishers

363 West Erie Street

Chicago, Illinois 60610

ISBN 0-89733-436-1

TO THE MEMORY OF

GERTRUDE SCHOEPPERLE LOOMIS

WHO ONCE WROTE IN MY COPY OF HER

Tristan and Isolt

Mais se maint chevalier le queroient chascuns par soi il seroit plus tost troues que se il nen aloit que un tout seul en la queste.

Prose Lancelot, I , 227.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

BOOK ONE

FROM KNIGHTS OF THE ROUND TABLE TO IRISH GODS

CHAPTER I

AN ITALIAN SCULPTURE AND A BRETON TALE

To think of Medieval Romance is to gaze through magic casements opening on the foam of perilous seas in faery lands forlorn: it is to dream of faery damsels met in forest wide by knights of Logres or of Lyones, Lancelot or Pelleas or Pellenore; it brings near the island valley of Avilion, deep-meadowed, happy, fair with orchard lawns and bowery hollows crowned with summer sea; we behold Bors, Perceval, and Galahad sailing in Solomons magic bark for the Land of Sarras; with Parsifal we listen bewildered to the haunting music of the Grail and witness that strange agonized ritual with a mute wonder.

In short, Medieval Romance is dominated by the legends of Arthur and the Table Round. It is they which during the twelfth century placed their enchantment upon Europe. In Sicily, Spain, Iceland, and the Kingdom of Jerusalem, the names of Gawain and Morgan le Fay came to be as well known as they were in England or France. So powerful was the spell of Arthurian legend that its great rival, the Carolingian epic, took over, as the Plerinage Charlemagne indicates, much of its supernatural machinery. Arthurian legend borrowed little from the chansons de geste, but the epics of Ogier and Huon de Bordeaux incorporate masses of Arthurian material. Quite properly, then, is our conception of Medieval Romance filled with the strange pageantry, charged with the mysterious glamour that distinguishes the Matter of Britain from other medieval cycles.

This strangeness, this mystery lies not simply in the common magical elements of folklore, the sudden metamorphoses and vanishings, the enchanted weapons and barges, the giants, dwarfs, and monsters. It lies also in the tantalizing suggestion which must occur at times to every sensitive reader that more is meant than meets the ear. It is not only Matthew Arnold who in reading the tales of the Mabinogion suspects that the medieval story-teller is pillaging an antiquity of which he does not fully possess the secret; he builds, but what he builds is full of materials of which he knows not the history, or knows by a glimmering tradition merely, stones not of this building, but of an older architecture, greater, cunninger, more majestical.

But so scattered, so battered are the relics of that older architecture that there are scholars who deny altogether that Arthurian romance is constructed out of the ruins of a pagan Pantheon. There are others, however, who have pointed out that Gawain, whose strength waxed and waned with the mounting and sinking of the sun in the heavens, must have been a solar hero; others have seen in the Grail legend the survival of a long forgotten initiation ceremony into a cult of fertility; others have traced the enchanter Mabon back through the Welsh Mabon son of Modron to Apollo Maponos, worshiped in Gaul and Britain. But there has been only one comprehensive attempt to discover the mythological concepts and figures which, like gigantic shadows thrown on a hillside, loom up behind the mail-clad knights and trimly girdled ladies of Camelot.

Sir John Rhys did not, however, work out the Celtic mythological system from the evidence of the Irish and Welsh legends themselves, but tried to fit them into the scheme which Max Muller had constructed largely from Sanscrit sources. Rhys further weakened his case by his patent ignorance of any but the Welsh and English versions of the Arthurian cycle.authority the tales of the Bretons they consider mere convention; the romances, broadly speaking, a late invention.

Without accepting Rhyss particular mythological identifications, it seems possible none the less to accept his basic theory and to agree whole-heartedly in the belief that most of the British and Armoric knights that encircle Uthers son where once gods or deified men. The fundamental stories about their births, their deaths, their combats, their loves, are, once understood, as good mythology as any that exists.

How and where shall we find our entrance from the world of romance into that Other World of the gods? A number of facts scattered about in books on archaeology, history, and literature, when brought together and correlated, enable us to imagine with fair accuracy a scene where knightly adventure and mythical significances seem clearly mingled in the tale of a Breton minstrel.

In November 1096 along the white road, bordered with grey-green olive orchards, leading into the city of Bari, far down in the heel of Italy, a long cavalcade of knights on jaded horses was riding. Their ringed hauberks were rusty, but their shields and fluttering pennons were gay with indigo, green, and cinnabar. It was a long journey they had come, for here were the Duke of Brittany, Alan Fergant, and his vassals, Riou de Loheac, Ralph de Gael, Conan de Lamballe, and Alan, steward of the Archbishop of Dol. The only explanation for its existence is the one already suggested that it was a story told by a Breton conteur in the presence of Crusaders and craftsmen gathered at Bari in 1096, a story so memorable and so graphic that it was at last fixed in marble at Modena. To this day it still bears witness to the power of that ancient tale. (See frontispiece.)

In the center is a castle surrounded by waters. On the keep hang a shield and spear. Two persons are within, a woman named Winlogee and a man named Mardoc, both much perturbed. The castle has two opposite entrances defended by wooden barbicans. Before the left barbican stands a churl labeled Burmaltus, brandishing a pick-like weapon called a baston cornu. Against him ride three knights, Artus de Bretania, Isdernus, and an unnamed knight. It is noteworthy that Isdernus wears neither helmet nor hauberk. From the other barbican gallops forth a knight, Carrado, striking with his lance the first of three attacking knights, Galvaginus, Galvariun, and Che.

Practically all archaeologists agree that the sculpture is to be The knights of the Modena sculpture, then, mirror for us the champions of the first Crusade. Such in appearance were Bohemund, Tancred, and Godfrey de Bouillon.

This carving was first brought directly to the attention of students of medieval romance by Foerster in 1898. He detected a curious resemblance between the sculptured scene and the story of Carado of the Dolorous Tower in the Vulgate Lancelot, which related the carrying off of Gawain by a gigantic knight named Carado; the imprisonment of Gawain in a castle with two perilous entrances, at one of which stood a churl; the pursuit of Carado by Galeschin, Ivain, Arthur, and Keu; and the final deliverance of Gawain by Lancelot, who slays Carado with his own sword, placed by a maiden whom Carado had abducted within Lancelots reach. Foerster pointed out that in this episode were the castle with two entrances, the churl standing before the gate, the lord of the castle Carado fighting against Arthur and his knights, Keu and Galeschin, who correspond to Che and Galvariun on the sculpture.

Next page