Sir Gawain

Knight of the Goddess

John Matthews

Inner Traditions

Rochester, Vermont

For Freya Reeves Lambides

who without knowing it sparked off this hook.

Gwalchmai, who pursued his quarry to the end of the wide world and back, could change at will to swan or wren, win furthur names, saunter in and out of the Other World, live forever on the lips of bards.

Peter Vansittart

from Parsifal

... Gawain, with his old curteisye,

Thought he were come ageyn out of Fairye...

Chaucer

from The Squires Tale

Acknowledgments

There is simply no way to express my debt to my wife, Caitlin, who not only found time to listen to my ravings in the midst of her own busy work schedule, but also helped shore up my flagging energies time after time, opened many of the secrets of the Goddess to me, and generally shared her own not inconsiderable understanding of the Matter of Britain.

My thanks must also go to Prudence Jones for her excellent translation of LEnfances Gauvain, for which all Gawain scholars should be grateful, and for her stimulating conversation on this and other topics.

To Dick Swettenham for his timely translation and summary of La Pulzella Gaia.

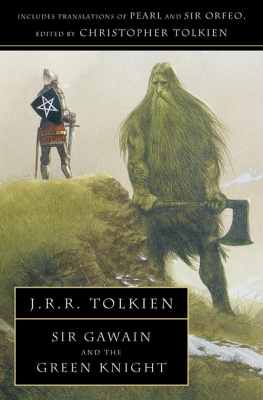

To my friend Richard Blackford, whose operas of Gawain and the Green Knight and Gawain and Ragnall have remained a deep source of inspiration to me.

To all those legions of explorers and commentators who went beforenaturally the mistakes are mine not theirs.

I have tried to look at every text, though several are in antique and sometimes unreliable editions. Where this was the case I have relied upon the exhaustive commentaries available, especially those of Professor Bruce, Alfred Nutt, and H.O. Sommer. For much of the background to Chapter 11 owe an especial debt to the work of R.S. Loomis, whose detailed research into the origins of Gawain proved some valuable links. Also particularly helpful was Keith Busbys exhaustive study of the French Gawain texts, without whose sharp eye and excellent scholarship, Chapters 6 and 7 would have been much the poorer.

Grateful acknowledgement also to the Scottish Academic Press Ltd, for permission to reprint the text of The Great Sorrow, which originally appeared in Volume 5 of The Carmina Gadelica by Alexander Carmichael.

Thanks also to Tim Cann, for the photo of Wetton Mill which appears on p. 190.

Finally I would like to thank Mildred Leake Day for her encouragement and for her generous foreword, and of course for her translation of De Ortu Waluuanii,39 a contribution without equal in Gawain scholarship.

Preface to the Second Edition

I was always drawn to Gawains passion and stubbornnesstraits that I am all too aware of sharing. It was Gawain who was the first to leap up and demand the right to follow a new quest or adventure, in which he seldom failed. It was Gawain who undertook the terrible test of the Green Knight and showed his willingness to admit to human flaws. Finally, it was Gawain whose anguish at the loss of a beloved brother helped to bring down the Fellowship of the Round Table. It was this last event and the way in which Gawain was represented in later interpretations of the Arthurian legends that set me off on a personal quest, resulting in the book you now hold.

In the twelve years since this book first appeared, research has added nothing significant to the interpretation of Gawain archetype. The single exception being the factof which I was unaware at the time of writingthat Gawain features as the main character in a late Irish romance, The Visit of the Grey Hammed Lady (The Visit of Sgil Isgaide Lithe). In its oldest translation the heros name is translated as Galahad; in reality it should have been Gawain. This revealed a new source in which the Knight of the Goddess undergoes a series of adventures in the Otherworld that in every way supports the later interpretations of his character. I was able to make my own version of this tale in The Book of Arthur (Vega, 2002), and I refer those interested in the story to that book, which also contains versions of the other main Gawain romances.

My findings on the character and history of Gawain have not been challenged to any significant degree, and I am elated that the book has proved useful as a starting point for several generations of students working in the field of Arthurian studies. It is a great pleasure to welcome this new edition, which remains unchanged apart from a few minor corrections.

John Matthews

Foreword

Sir Gawain, nephew of the great King Arthur, figures in much of the extensive literature of the Arthurian legend. Although this body of material was written down long after the pagan era had ended, the tales preserve hints of the ancient story that celebrated the heroes and rituals of the pre-Christian ages. Anthropologists, folklorists, and archeologists working with the Celtic traditions have identified many gods and goddesses, but perhaps the most pervasive is the Goddess of the Land, sometimes called the Sovereignty, sometimes The Great Mother, and often represented as a triple figure. Although Gawain serves no person identified specifically as The Great Goddess, he is involved with women of mysterious characteristicsMorgan (sometimes called a Goddess), Lady Bercilak, Dame Ragnell, even Guenivere. These ladies can be identified by name or by story motifs with Irish and Welsh pagan figures of an earlier time, as can Gawain himself. Behind these stories is a compelling feminine power dimly remembered in Western culture as Mother Nature, The Mother Country, the Muse, and even Lady Luck.

Beginning with the massive work of Sir James Frazer almost a century ago, scholars have tried to reconstruct the largely lost pagan cultures. Frazer, in The Golden Bough (1898), presents a pagan past based on the agricultural year with rituals for increasing the fertility of soil and flocks. His research on the sacral kingship and the battles between summer and winter have done much to increase our understanding of the relationship between the king and his land that appears in the Arthurian legend as the Wounded King and the Wasteland. Frazer does not deal as extensively with the feminine principles, although he does touch on the Corn Goddess in her two aspects of hag and bride, which he explains as a variation of the Demeter Persephone concept:

Judged by these analogies [the customs he has recorded] Demeter would be the ripe crop of this year; Persephone would be the seed-corn taken from it and sown in autumn, to reappear in spring. The descent of Persephone into the lower world would thus be a mythical expression for the sowing of the seed; her reappearance in the spring would signify the sprouting of the young corn. In this way the Persephone of one year becomes the Demeter of the next... (Theodore H. Gaster, ed., 1959, p. 422)

Although Frazers golden mistletoe bough may now be considered merely a green branch broken by a suppliant and much of his collection of folklore and ritual frowned upon as not collected with proper professional discipline, Frazers influence on twentieth century scholars and artists is immeasurable. Jessie Weston, T.S. Eliot and John Boorman, to name but a few, have touched on fertility, the king, and the wasteland.

C.G. Jung, perceiving that the patterns of the ancient mythology continue to recur in modern literature as well as in the dreams and hallucinations of his patients, proposes that these myths exist as archetypes in the unconscious, providing modern man with the patterns for coping with the great crises of human birth, puberty, and death. Jung identifies the feminine principle as the anima, dividing her into mirror aspects, the Good Mother, and the Terrible Mother. He explains that the creative principle of great art is in the evoking of the archetypes and that it is generated from the unconscious of the artist:

Next page