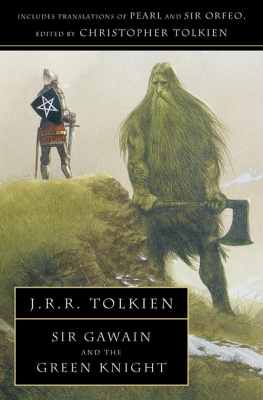

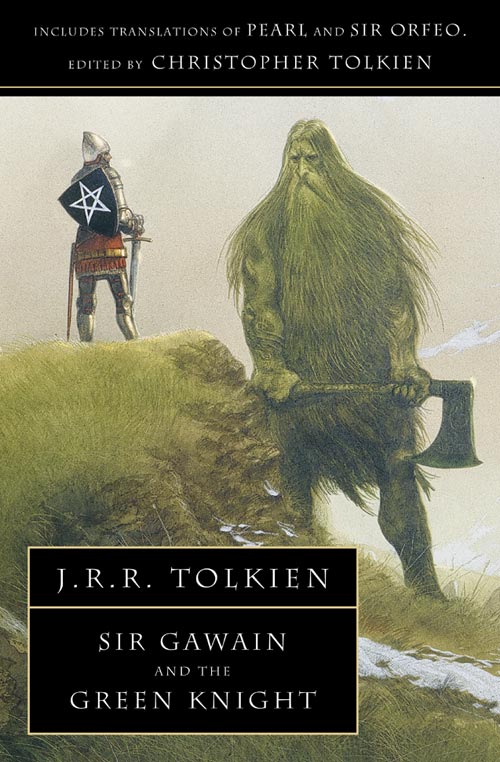

CONTENTS When my father, Professor J. R. R. Tolkien, died in 1973 he left unpublished his translations of the medieval English poems

Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, Pearl and

Sir Orfeo. A form of his

Pearl translation was in existence more than thirty years ago, though it was much revised later; and that of

Sir Gawain soon after 1950. The latter was broadcast on the BBC Third Programme in 1953.

His version of Sir Orfeo was also made many years ago, and had been (I believe) for long laid aside; but he certainly wished to see it published. He wished to provide both a general introduction and a commentary; and it was largely because he could not decide on the form that these should take that the translations remained unpublished. On the one hand, he undoubtedly sought an audience without any knowledge of the original poems; he wrote of his translation of Pearl: The Pearl certainly deserves to be heard by lovers of English poetry who have not the opportunity or the desire to master its difficult idiom. To such readers I offer this translation. But he also wrote: A translation may be a useful form of commentary; and this version may possibly be acceptable even to those who already know the original, and possess editions with all their apparatus. He wished therefore to explain the basis of his version in debatable passages; and indeed a very great deal of unshown editorial labour lies behind his translations, which not only reflect his long study of the language and metre of the originals, but were also in some degree the inspiration of it.

As he wrote: These translations were first made long ago for my own instruction, since a translator must first try to discover as precisely as he can what his original means, and may be led by ever closer attention to understand it better for its own sake. Since I first began I have given to the idiom of these texts very close study, and I have certainly learned more about them than I knew when I first presumed to translate them. But the commentary was never written, and the introduction did not get beyond the point of tentative beginnings. My concern in preparing this book has been that it should remain his own; and I have not provided any commentary. Those readers whom he most wished to reach will be content to know that in passages of doubt or difficulty these translations are the product of long scrutiny of the originals, and of great pains to embody his conclusions in a rendering at once precise and metrical; and for explanations and discussions of detail reference must be made to editions of the originals. But readers who are wholly unacquainted with these poems will wish to know something about them; and it seemed to me that if it were at all possible the translations should be introduced in the words of the translator himself, who gave so much time and thought to these works.

I have therefore composed the introductory and explanatory parts of the book in the following way. The first section of the Introduction, on the author of Sir Gawain and Pearl, is derived from my fathers notes. The second section, on Sir Gawain, is (in slightly reduced form) a radio talk which he gave after the broadcasts of his translation. For the third section, the only writing of his on Pearl that I could find suitable to the purpose was the original draft for an essay that was subsequently published in revised form. After my father and Professor E.V. Gordon had collaborated in making an edition of Sir Gawain, which was published in 1925, they began work on an edition of Pearl.

In the event, that book was almost entirely the work of Professor Gordon alone, but my fathers contribution to it included a small part of the Introduction; and the essay is here reproduced in the form it finally took as the result of their collaboration. Its appearance here has been made possible through the generosity of Mrs I. L. Gordon. I wish also to thank the Delegates of the Clarendon Press for their permission to use it. I was not able to discover any writing by my father on the subject of Sir Orfeo.

Here therefore, in keeping with my general intentions for the book, I have restricted myself to a very brief factual note on the text. Since a primary object of these translations was the close preservation of the metres of the originals, I thought that the book should contain, for those who want it, an account of the verse-forms of Sir Gawain and Pearl. The section on Sir Gawain is composed from drafts made for, but not used in, the introductory talk to the broadcasts of the translation; and that on the verse-form of Pearl from other unpublished notes. There is very little in these accounts (and nothing that is a matter of opinion) that is not in my fathers own words. It is inevitable that in thus using materials written at different times and for different purposes the result should not be entirely homogeneous; but it seemed to me better to accept this consequence than not to use them at all. At his death my father had not finally decided on the form of every line in the translations.

In choosing between competing versions I have tried throughout to determine his latest intention, and that has in most cases been discoverable with fair certainty. At the end of the book I have provided a short glossary. On the last page will be found some verses translated by my father from a mediaeval English poem. He called them Gawains Leave-taking, clearly with reference to the passage in Sir Gawain where Gawain leaves the castle of Sir Bertilak to go to the tryst at the Green Chapel. The original poem has no connection with Sir Gawain; the verses translated are in fact the first three stanzas, and the last, of a somewhat longer poem found among a group of fourteenth-century lyrics with refrains in the Vernon manuscript in the Bodleian Library at Oxford. Christopher Tolkien I Sir Gawain and the Green Knight and Pearl are both contained in the same unique manuscript, which is now in the British Museum.

Neither poem is given a title. Together with them are two other poems, also title-less, which are now known as Purity (or Cleanness), and Patience. All four are in the same handwriting, which is dated in round figures about 1400; it is small, angular, irregular and often difficult to read, quite apart from the fading of the ink in the course of time. But this is the hand of the copyist, not the author. There is indeed nothing to say that the four poems are the works of the same poet; but from elaborate comparative study it has come to be very generally believed that they are. Of this author, nothing is now known.

But he was a major poet of his day; and it is a solemn thought that his name is now forgotten, a reminder of the great gaps of ignorance over which we now weave the thin webs of our literary history. But something to the purpose may still be learned of this writer from his works. He was a man of serious and devout mind, though not without humour; he had an interest in theology, and some knowledge of it, though an amateur knowledge, perhaps, rather than a professional; he had Latin and French and was well enough read in French books, both romantic and instructive; but his home was in the West Midlands of England: so much his language shows, and his metre, and his scenery. His active life must have lain in the latter half of the fourteenth century, and he was thus a contemporary of Chaucers; but whereas Chaucer has never become a closed book, and has continued to be read with pleasure since the fifteenth century, Sir Gawain and the Green Knight and Pearl are practically unintelligible to modern readers. Indeed in their own time the adjectives dark and hard would probably have been applied to these poems by most people who enjoyed the works of Chaucer. For Chaucer was a native of London and the populous South-East of England, and the language which he naturally used has proved to be the foundation of a standard English and literary English of later times; the kind of verse which he composed was the kind which English poets mostly used for the next five hundred years.