Michael Lee Lanning

INSIDE THE CROSSHAIRS

Snipers in Vietnam

To

Gerald Hugh Gerry Corcoran

CHAPTER 1

All in a Days Work: The Single Well-Aimed Shot

As a different kind of war, Vietnam required tactics, operational procedures, and weapons uniquely adapted for the conflict. The U.S. Army and Marine Corps especially had to constantly adjust fighting conceptsrevamping tried-and-true techniques and designing innovative methodsto counter an enemy whose operations varied from Vietcong hit-and-run guerrilla tactics to North Vietnamese Army multi-division offensives.

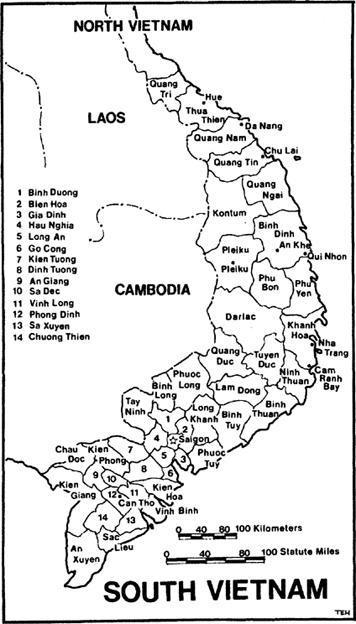

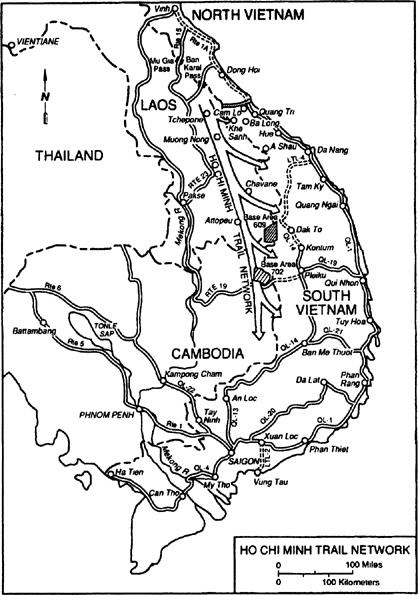

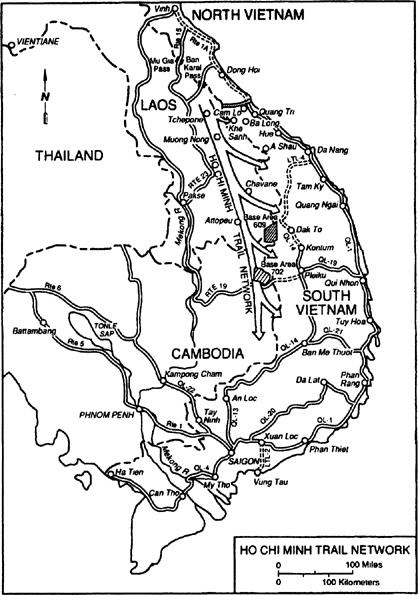

Of all these adjustments and changes during the war, one of the most effective, and certainly the most economical, was the use of individual marksmen known as snipers. While taking advantage of individual marksmanship skills was clearly not new to warfare, the way the U.S. military developed the expertise to new standards in Southeast Asia certainly was. In terms of the efficiency they achieved, army and Marine marksmen consistently engaged and killed enemy soldiers at ranges often exceeding 800 meters with a single round from special, telescope-equipped rifles. From the densely forested mountain highlands near the Demilitarized Zone to the open spaces of the watery Mekong River Delta, American snipers consistently downed enemy soldiers before their targets even heard the crack of their rifles.

In terms of economics, the innovative use of snipers in Vietnam meant that virtually every bullet produced a body counta statistic drastically different from bullet-to-body ratios for other wars and other infantrymen in Vietnam. Studies of frontline combat during World War II reveal that U.S. troops expended 25,000 small arms rounds for every enemy soldier they killed. In the Korean War the number doubled to 50,000 rounds per enemy death. By the time the United States went to war in Southeast Asia, technological advances in weapons had made it possible to place a fully automatic rifle in the hands of every American infantryman, and the firepower of fully automatic rock and roll resulted in the expenditure of 200,000 rounds of ammunition for every enemy body.

Army and Marine snipers, on the other hand, produced a dead enemy for nearly every round fired. U.S. snipers in Vietnam averaged one kill for every 1.3 to 1.7 rounds expended. According to Lieutenant General John H. Hay Jr., who commanded the armys 1st Infantry Division in 1967 and wrote Tactical and Material Innovations as a part of the Department of the Armys Vietnam Studies series in 1974, The use of snipers was not new in Vietnam, but the systematic training and employment of an aggressive, offensive sniper teama carefully designed weapon systemwas. A sniper was no longer just the man in the rifle squad who carried the sniper rifle; he was the product of an established school.

Yet, when the United States entered the Vietnam War, it had no trained snipers or sniper units. Although the military had organized, trained, and fielded snipers during earlier U.S. conflicts, sniper units had been quickly disbanded and the shooters discharged or returned to the ranks of the infantry when peace returned. Expert marksmen, who could fire with no warning and kill with a single shot, were necessities of war that, at times of peace, a fair-minded American society preferred to forget ever existed.

But at war again, both services recognized the need to renew sniper training. The Marines fielded their first sniper teams in Vietnam in October 1965; the army, a bit slower, did not begin in-country sniper training until the spring of 1968. In the meantime, a few expert Army riflemen secured sniper weapons left over from the Korean War and rifles used by marksmanship competition teams to unofficially begin adapting to the unique war zone.

Even though policy eventually caught up with practicality and snipers received official sanction and support, what became one of the wars most efficient weapon systems was ultimately the direct result of the individual men behind the scopes. These men met the established criteria for acceptance into training and most often exceeded the expectations of their commanders. In doing so, they used their native talents and acquired skills to eliminate the enemy and save American lives.

Lieutenant General Julian J. Ewell, who assumed command of the 9th Infantry Division in February 1968 and took the leadership role in establishing army snipers in Vietnam, recorded some of his experiences with snipers and their expertise in Sharpening the Combat Edge, another Vietnam Studies title, in 1974. Ewell wrote, Our most successful sniper was Sergeant Adelbert F. Waldron III, who had 109 confirmed kills to his credit. One afternoon he was riding along the Mekong River on a Tango boat when an enemy sniper on shore pecked away at the boat. While everyone else on board strained to find the antagonist, who was firing from the shoreline over 900 meters away, Sergeant Waldron took up his sniper rifle and picked off the Vietcong out of the top of a coconut tree with one shot (this from a moving platform). Such was the capability of our best sniper. We had others, too, with his matchless vision and expert marksmanship.

The following individual accounts provide a look into the typical days work of American snipers in Vietnam.

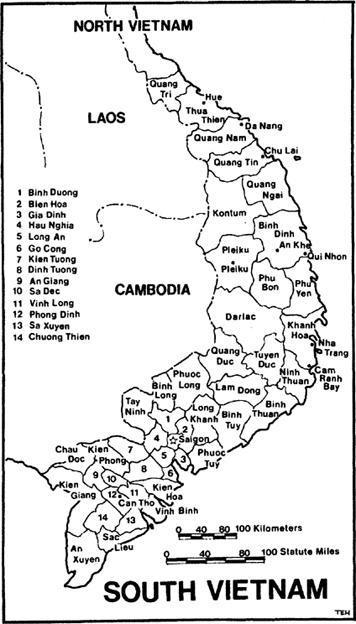

Gary M. White of Utica, New York, joined the Marine Corps in January 1969 and shortly thereafter reported to Parris Island for boot camp. The following September, White arrived in Vietnam, where he joined M Company, 3rd Battalion, 26th Regiment, 1st Marine Division. White recalls, I had been in Vietnam for a couple of months when a sergeant with a sniper team temporarily attached to the company said they needed recruits for the regiments scout-sniper platoon. I volunteered. After an interview to confirm that I had shot expert in basic, I went to Da Nang for sniper training.

The sniper school issued me a Remington Model 700 rifle with a 39 variable-power scope that had an internal 600-meter range finder. I was already a good shot before the training but during the ten-day school I became even better. The bolt rifle, as we called the Remington, was a great weapon. I never had any trouble with it.

Upon graduation I reported to the 26th Marine Regiment Headquarters Company Scout-Sniper Platoon. It had a lieutenant platoon commander, a platoon sergeant, an armorer, and twenty-eight snipers organized into fourteen two-man teams. Most everyone was twenty years old like myself or a year or so younger or older. Me and one Marine from Connecticut and a surfer from California were the only ones not from the South or the western mountain states. Most had done a lot of game hunting before joining the corps.

Like every newly assigned sniper, I began as the observer, searching for targets, spotting rounds, and providing security for the primary shooter. Due to lots of guys completing their tours, I moved up from observer to shooter after only a few weeks.

My first mission as the senior team member came in November 1969. As soon as I got the order, I went to a makeshift firing range at the edge of the base and doped, or zeroed, my weapon. I reconfirmed my zero with three or four shots and then packed up my rucksack for the mission. We snipers usually went pretty light in the field since we rarely stayed out more than five days to a week. I wore camouflage utilities made up of a pattern of shades of green, tan, and black along with a soft-brim boonie hat and the issue jungle boots.