Table of Contents

Introduction

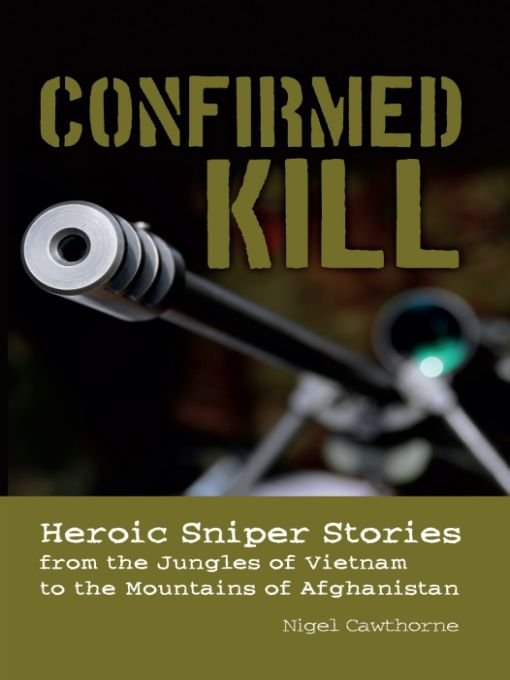

Not all those who fall to snipers bullets are considered confirmed kills. To get a confirmed kill, the body must be examined to make sure the enemy is dead, then it is searched for weapons, maps, and other documents. Traditionally, the sniper had to fill out a kill sheet. This carried the name of the sniper and his spotter, if he had one with him; the date and time of the kill; the number of the rifle and the scope the sniper used; the map coordinates of the incident or where the body or bodies were left; and the number of enemy engaged during the incident, their direction of travel, and details of the weapons they were carrying. Details of the deceased were also included, giving their sex and approximate age. The skin, eyes, teeth, and fingernails were checked for signs of malnutrition or disease. The state of their uniform and equipment was noted, along with any food they may have been carrying. The sheet then had to be signed by the highest ranking officer present. It was rare for the bodies to be brought back to an American base for burial. Usually they were left where they lay. If there was no time to complete the paperwork in the field, snipers were trained to develop their powers of observation so that the kill sheet could be filled out when they returned to a secure area. No kill sheet, no confirmed kill. If it is not possible to reach the body due to the intensity of fire, the fatality is listed as a probable.

All soldiers are trained to destroy an opponent, but snipers have honed the art of killing to a fine edge. Even before 9/11 intensified the nations fight against terrorism, US Army leaders had recognized that traditional sniper techniques would not work well in a world where terrorists hit and ran from city buildings and busy streets. The army began teaching urban sniper techniques in a five-week course at Fort Benning, Georgia, where these elite warriors learn to stalk their prey, conceal their movements, spot telltale signs of an enemy shooter, and take down a target with a single shot. To be considered for the school, a soldier must qualify as an expert marksman, pass a physical examination, and undergo a psychological screening. The rigorous course fails more than half its students.

The US Marine Corps Sniper School offers what is widely regarded in the military as the finest sniper training program. However, it is open to candidates from all branches of the US armed services. They must have a rank between lance corporal and captain, and be infantry trained. Recruits need 20/20 vision in both eyes, though glasses and contact lenses are allowed. Color blindness is a problem though. They have to be going on to a posting as a scout-sniper and have completed at least 12 months of service, unless they are a reservist. No one with a court martial need apply and recruits must have stayed out of trouble for at least six months. They must be a volunteer with no history of mental illness. Otherwise they must be physically fit and be able to swim. It is also recommended that they have attended courses in most scout-sniper skills, including land navigation, patrolling, reconnaissance, and calling in supporting armament. Candidate must be currently rated as rifle experts, though they do not need to be dead shots. That can be taught.

The course begins with range shooting at 300, 500, 600, 700, 800, 900, and 1,000 yards. At ranges up to 800 yards, students will be expected to hit moving targets. Using binoculars and a spotting scope, they must be able to pick out hidden objects at long distances and to produce a detailed field sketch of any area of operation. The student will then move on to stalking and shooting targets at unknown distances, before being taught advanced field skills and mission employment.

The failure rate from the Marine Corps Sniper School is usually around 60 percent, though it can be much higher. But the skill and dedication of the sharpshooters who graduate is unmatched, and they know what it takes to be a top marksmandeadly aim, iron nerve, killer instincts, and unwavering courage. The military do not want their snipers to be hotheads or mindless killers. They want scout-snipers who are independently minded and self-reliant. After all, they will often be called on to risk their lives on their own in hostile territory, far beyond friendly lines.

Snipers must also be deeply committed to their country, their cause, and their service. On their shoulders lies the life or death of the other men, the ordinary grunts, who follow behind. If a sniper can take out key personnel and throw the enemy into confusion, they can make the difference between a battle lost or won.

In this book are stories of men who have attempted to live up to these high ideals. Many have excelled. Some have shown human failings. The question for every reader is, Could I have performed as well under the circumstances? I know that I, the author, certainly could not.

Nigel Cawthorne

Bloomsbury, UK, October 2011

PART ONE

VIETNAM

CHAPTER ONE

First Blood to the Marines

When lead elements of the 3rd Marine Regiment, 3rd Marine Division first landed in force in Vietnam in March 1965, they found they had a problem. The Communist insurgentsthe Vietcongfound that they could move around with relative impunity. They were safe from the marines small-arms fire, especially at long range. What was needed to fight them were snipers.

In September 1965, Captain Robert A. Russell was tasked with setting up a sniper team and began recruiting scout-snipers for the 3rd Division in Da Nang. One of those seconded into the team was Corporal Gary Hillbilly Edwards from Tennessee. At boot camp he had qualified as an expert in marksmanship, scoring 228 out of 250. There were 20 men on the course. After five days training, they were each given a Winchester Model 70 .30-06 bolt-action sniper rifle with a box of Camp Perry match ammunition.

Twenty rounds each, Gunnery Sergeant George Hurt told them. I want 20 kills. One shot, one kill.

But having trained snipers in the division was still a new departure for the marines, and they had yet to learn how to use them. At first the snipers were put on sentry duty. Then when they complained, they were sent out on patrol with regular grunts. Next came rather more aggressive patrolling. Even then they would be escorted by men carrying M14s, M60 machine guns, and M79 grenade launchers. Eventually, the snipers were let loose on their own and were sent out into enemy territory where, under the rules of engagement, they could kill anyone they saw, provided the targets were carrying weapons.

On their first mission, Corporal Edwards, Sergeant Brown, and a lance corporal known as Kentuckyalso graduates of Russells sniper coursewere put on a Sikorsky H-34 Choctaw helicopter and flown out to a post manned by South Vietnamese soldiers. The following morning, a lieutenant with the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) led them out to a jungle track which, he said, was used by the Vietcong at about 0930 hours each morning.

Edwards, Brown, and Kentucky set up on a hillside overlooking the track where it emerged into a clearing. The rest of the ARVN patrol hid themselves in case they were needed to provide covering fire.

At 0905 hours, five Vietcong appeared. Dressed in black pajamas, they looked happy and relaxed. Edwards was to take the first one; Brown and Kentucky, the two that followed. They were around 1,000 yards (914 meters) away. As he looked though his scope, Edwards could see that the lead man was youngbut then, so was he. With the crosshairs on the target, he followed his training to the letter. First he breathed in, then slowly out halfway and stopped, then he squeezed the trigger gently, as his instructor had told him, as if it were a womans nipple. The lead man fell, followed by the two behind him. The other two VC ran back toward the jungle. The ARVN patrol fired on them with an M60, but they escaped. Nevertheless, the platoon commander was happy with the body count.