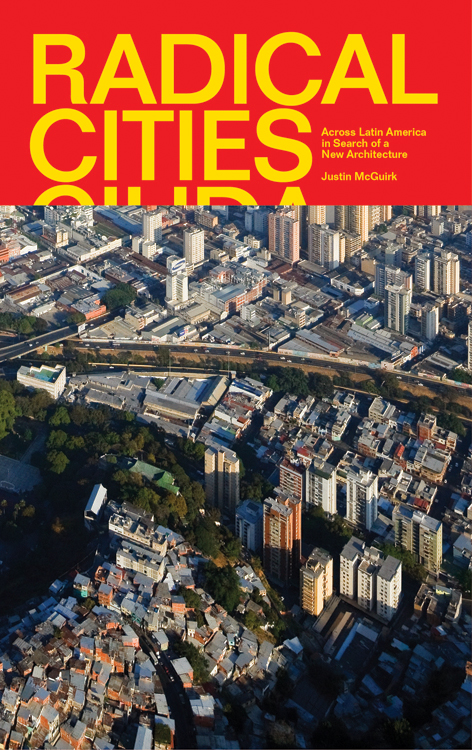

Radical Cities

Across Latin America in Search

of a New Architecture

Justin McGuirk

For Dina

First published by Verso 2014

Justin McGuirk 2014

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

www.versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

ISBN-13: 978-1-78168-280-7

eISBN-13: 978-1-78168-655-3 (UK)

eISBN-13: 978-1-78168-281-4 (US)

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

McGuirk, Justin.

Radical cities : across Latin America in search of a new architecture / Justin McGuirk.

pages cm

ISBN 978-1-78168-280-7 (hardback)

1. Architecture and society Latin America History 21st century. 2. Cities and towns Latin America Growth. 3. City dwellers Political aspects Latin America. I. Title.

NA2543.S6M39 2014

720.103098dc23

2013051123

Typeset in Fournier by MJ & N Gavan, Truro, Cornwall

Printed in the US by Maple Press

Latin America is Africa, Asia and Europe at the same time.

Flix Guattari in Molecular Revolution in Brazil

What do you want to be? the anarchist asked young people in the middle of their studies. Lawyers, to invoke the law of the rich, which is unjust by definition? Doctors, to tend the rich, and prescribe good food, fresh air, and rest to the consumptives of the slums? Architects, to house the landlords in comfort? Look around you, and then examine your conscience. Do you not understand that your duty is quite different: to ally yourselves with the exploited and to work for the destruction of an intolerable system?

Victor Serge paraphrasing a pamphlet by Peter Kropotkin,

in Memoirs of a Revolutionary

Contents

Saturday, June 30, 1962.

9:35 a.m. President Kennedy arrives at the housing project.

Tours project brief ceremony.

This I found in the John F. Kennedy Librarys digital archive, in the schedule of the presidents official visit to Mexico City in 1962. Id been told that on this trip hed been taken to see Nonoalco-Tlatelolco, a vast housing estate, the biggest of its kind in Latin America. And that made sense. In the 1960s, what else would you show the US president to flaunt your modernising nation if not industrialised ranks of housing stretching as far as the eye could see? Mechanisation, social mobility and economic power all wrapped up in one potent image.

My source was wrong, however. A few pages further into Kennedys itinerary briefing it emerges that it was the Unidad Independencia housing project that he visited, not Tlatelolco, which was still under construction. You can almost feel his hosts frustration. Two years later, the city would have an infinitely more impressive site to show off. The photographs of Tlatelolco taken when it was completed in 1964 are some of the most powerful images of social housing Ive ever seen. Row upon row of megablocks stand proudly over the low-rise sprawl of Mexico City. With their gridded, ultra-repetitive facades, they resemble banks of mainframe computers, or server farms before the fact.

Here was the modernist utopia built on a scale that Le Corbusier had dreamt of but was never able to realise. This city within the city comprised 130 buildings, providing 15,000 apartments. At its height, Tlatelolco housed nearly 100,000 people. It was the kind of solution that the problem of Mexico City seemed to demand, a problem of population explosion fuelled by industrialisation and the accompanying mass migrations from the countryside. What was a population of a little over a million in 1940 was on its way to becoming 15 million by 1980.

Tlatelolcos architect was Mario Pani. Like other prominent Latin American architects of his generation, he was trained in Europe, indeed in Paris, where he attended the cole des Beaux-Arts in the 1920s before imbibing the spirit of Corbusian modernism. An earlier housing project, the Presidente Miguel Alemn estate, built in 1948, even uses the zigzagging blocks of the Ville Radieuse, Corbus blueprint for an ideal city. But while on one level Pani was being derivative, on another he was bringing those unfulfilled ideas to fruition. For Tlatelolco took the modernist idea of social housing to its logical, many would say absurd, conclusion. If, in the mid twentieth century, the city of the future would comprise rows of megablocks sitting in parklands and gardens, then the future looked like Tlatelolco.

Indeed, Panis plan had been to build five or six Tlatelolcos on that site, with an extension of three million square metres. In his eyes, much of Mexico City deserved the wrecking ball so that a new vision could flourish. Invoking Le Corbusier to the end, Pani never accepted that the Swiss genius might be, to borrow Henri Lefebvres description, a good architect but a catastrophic urbanist. In 1964, Pani was still progress.

In Luis Buuels film about a group of delinquents in Mexico City, Los Olvidados (The Forgotten), there is a scene in which a youth who has settled into a life of crime murders a rival and steals the money out of his pockets. Its a primal scene, like watching Cain kill Abel, except that in the background is the steel frame of a modern building. Is it housing? Its impossible to say. But, rising out of a wasteland, this space-frame is surely a symbol of approaching progress. In Buuels unremittingly bleak portrait of life in Mexico City in 1950, crime is depicted as the inevitable result of poverty. The fleeting shot of that construction site is arguably the only moment of hope: it suggests change, modernism riding to the rescue.

It is not Tlatelolco that is being erected in the film, but it might as well be. The estate was built on the site of an overcrowded slum district, and Panis design, commissioned by the government, was intended to rehouse its inhabitants while bringing in middle-class residents to create social diversity. In short, it was an old-fashioned slum clearance. Pani matched the extreme density of the slum he was replacing, which was 1,000 inhabitants per hectare, but with sanitised, vertical machines surrounded by acres of public space. We can quibble with the vision, on both urbanistic and aesthetic grounds, but where it went wrong was in its outcome. Intended for the poor, Tlatelolco ended up being occupied largely by bureaucrats and workers at the state rail and health companies. As usual, the slum-dwellers were shunted elsewhere. This was the key failing of a scheme that came to be notorious for altogether different reasons.

At the heart of the estate is a historic site. The ruins of a pyramid mark the spot where the Aztecs were finally defeated by the Spanish, and right next to it stands the sixteenth-century church of Santiago Tlatelolco that heralded the new era. Pani incorporated these pivotal monuments into a centrepiece called the Plaza de las Tres Culturas, a broad square rimmed by his brutalist apartment blocks. The three cultures meeting here were the pre-Columbian, the colonial and the modern, providing a symbolic ensemble that tied a modernising Mexico to its past. But Panis architectural allegory was to be overshadowed by tragedy.