Also by James D. Hornfischer

The Last Stand of the Tin Can Sailors (2004)

Ship of Ghosts (2006)

Bantam Books  New York

New York

Copyright 2011 by James D. Hornfischer

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Bantam Books, an imprint of The Random House Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

B ANTAM B OOKS and the rooster colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Excerpts from unpublished writings by Robert D. Graff copyright 2011 by Robert D. Graff. Used by permission.

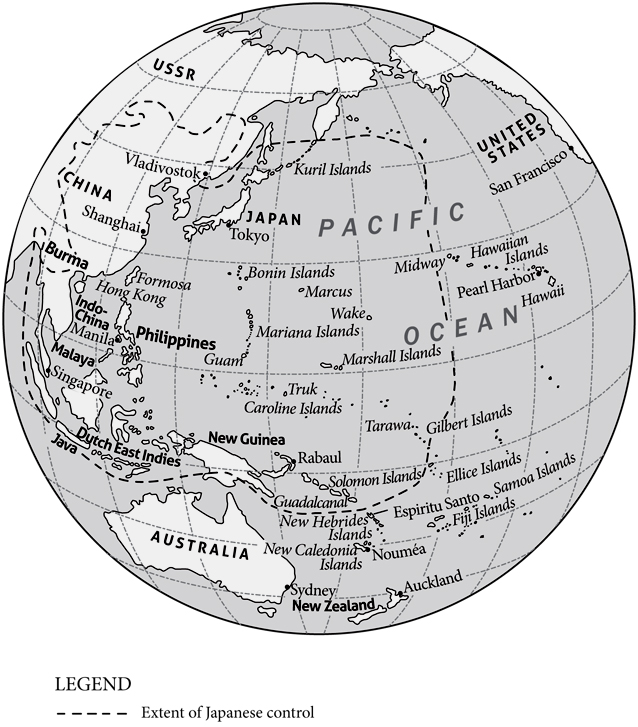

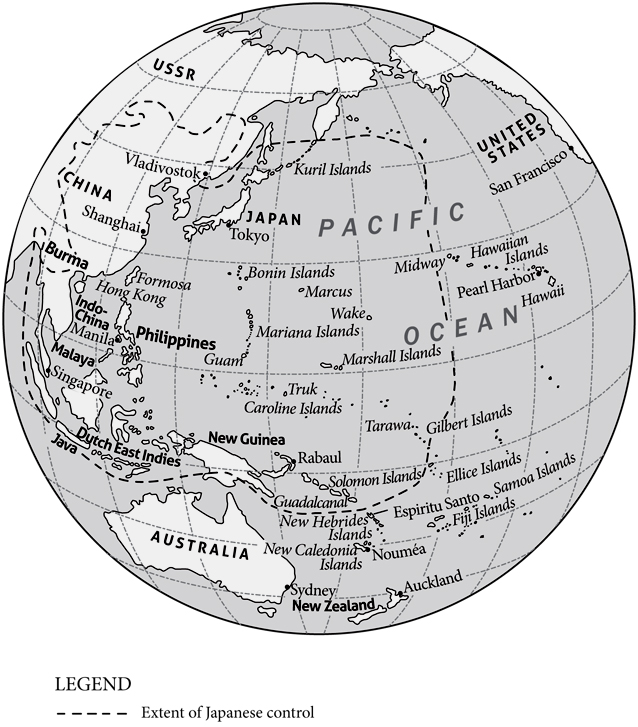

Endpaper map by Jeffrey L. Ward

Interior maps by Lum Pennington

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

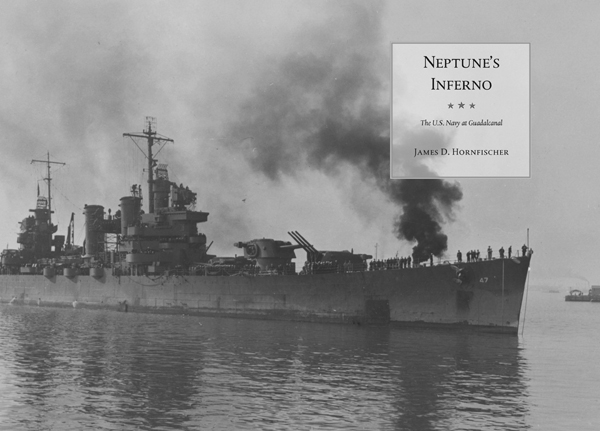

Hornfischer, James D.

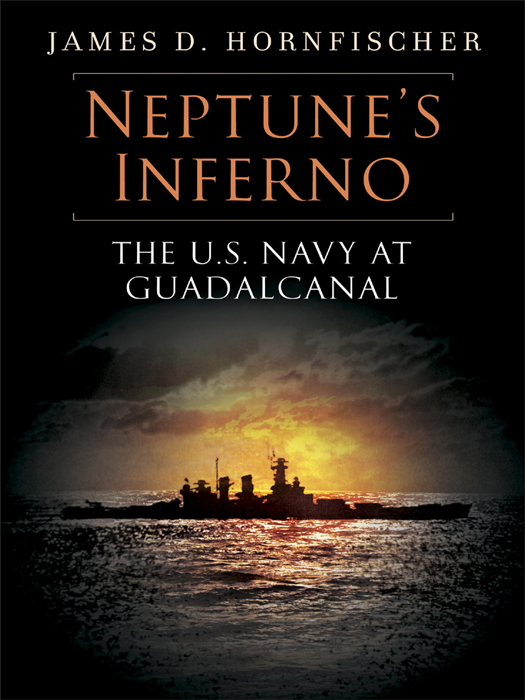

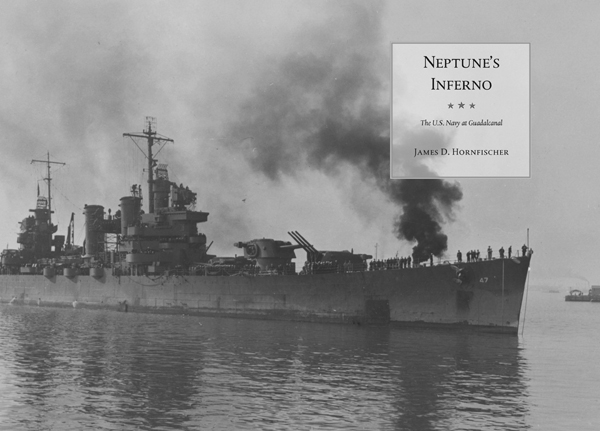

Neptunes inferno: the U.S. Navy at Guadalcanal / James D. Hornfischer.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

eISBN: 978-0-553-90807-7

1. Guadalcanal, Battle of, Solomon Islands, 19421943. 2. World War, 19391945Naval operations, American. 3. United States. NavyHistoryWorld War, 19391945. 4. United States. NavyBiography. 5. VeteransUnited StatesInterviews. 6. Guadalcanal, Battle of, Solomon Islands, 19421943Personal narratives, American. I. Title.

D767.98.H665 2011

940.54265933dc22

2010027231

www.bantamdell.com

v3.1

In memory:

C HARLES D. G ROJEAN

Rear Admiral, USN

19232008

Sailor, Leader, Teacher

Never have the gods of all the tribes put upon the seas such monsters as man now sends over them. Their steel bowels, grinding and rumbling below the splash of the sea, are fed on quarried rock. Their arteries are steel, their nerves copper, their blood red and blue flames. With the prescience of the supernatural, they peer into space. Their voices scream through gales, and they whisper together over a thousand miles of sea. They reach out and destroy that which the eye of man cannot perceive.

But all this terribleness will vanish, returning again into the inanimate whenever the capacity and vigor of the guiding mind deteriorates or is worn down by the years that have stolen away the quick grasp of youth.

Homer Lea, The Valor of Ignorance (1909)

CONTENTS

PART I

SEA OF TROUBLES

PART II

FIGHTING FLEET RISING

PART III

STORM TIDE

PART IV

THE THUNDERING

MAPS

TABLES

PROLOGUE

Eighty-two Ships

ON FRIDAY, AUGUST 7, 1942, EIGHTY-TWO U.S. NAVY SHIPS MANNED by forty thousand sailors, shepherding a force of sixteen thousand U.S. Marines, reached their destination in a remote southern ocean and spent the next hundred days immersed in a curriculum of cruel and timeless lessons. No fighting navy had ever been so speedily and explosively educated. In the conflict that rolled through the end of that trembling year, they and the thousands more who followed them learned that technology was important, but that guts and guile mattered more. That swiftness was more deadly than strength, and that well-packaged surprise usually beat them both. That if it looked like the enemy was coming, the enemy probably was coming and you ought to tell somebody, maybe even everybody. That the experience of battle forever divides those who talk of nothing else but its prospect from those who talk of everything else but its memory.

Sailors in the war zone learned the arcane lore of bad luck and its many manifestations, from the sight of rats leaving a ship in port (a sign that she will be sunk) to the act of whistling while at sea (inviting violent winds) to the follies of opening fire first on a Sunday or beginning a voyage on a Friday (the consequences of which were certain but nonspecific, and thus all the more frightful).

They learned to tell the red-orange blossoms of shells hitting targets from the faster flashes of muzzles firing the other way. That hard steel burns. That any ship can look shipshape, but if you really want to take her measure, check her turret alignments. That torpedoes, and sometimes radios, keep their own fickle counsel about when they will work. That a war to secure liberty could be waged passionately by men who had none themselves, and that in death all sailors have an unmistakable dignity.

Some of these were the lessons of any war, truisms relearned for the hundredth time by the latest generation to face its trials. Victory always tended to fly with the first effective salvo. Others were novel, the product of untested technologies and tactics, unique to the circumstances of Americas first offensive in the Pacific: that you could win a campaign on the backs of stevedores expert in the lethal craft of combat-loading cargo ships; that the little image of an enemy ship on a radar scope will flinch visibly when heavily struck; that rapid partial salvo fire from a director-controlled main battery reduces the salvo interval period but complicates the correction of ranges and spots.

In the far South Pacific, you were lucky if your sighting report ever reached its recipient. Even then, the plainest statement of fact might be subject to two or more interpretations of meaning. You learned that warships smashed and left dead in the night could resurrect themselves by the rise of morning, that circumstances could conspire to make your enemy seem much shrewder than he ever really could be, and that as bad as things might seem in the midst of combat, they might well be far worse for him. That you could learn from your opponents success if your pride permitted it, and that the best course of action often ran straight into the barriers of your worst biases and fears. That some of the worst thrashings you took could look like victories tomorrow. That good was never good enough, and if you wanted Neptune to laugh, all you had to do was show him your operations plan.

This book tells the story of how the U.S. Navy learned these and many other lessons during its first major campaign of the twentieth century: the struggle for the southern Solomon Islands in 1942. The American fleet landed its marines on Guadalcanal and Tulagi in early August. The Japanese were beaten by mid-November and evacuated in February. What happened in between was a story of how America gambles on the grand scale, wings it, and wins. Top commanders on both sides were slain in battle or perished afterward amid the shame of inquiries and interrogations. A more lasting pain beset the living. Reputations were shattered, grudges nursed. The Marine Corps would compose a rousing institutional anthem from the notion, partly true, that the Navy had abandoned them in the fights critical early going. But the full story of the campaign turns the tale in another direction, seldom appreciated. Soon enough, the fleet threw itself fully into the breach, and by the end of it all, almost three sailors had died in battle at sea for every infantryman who fell ashore. The Corps debt to the Navy was never greater.

New York

New York