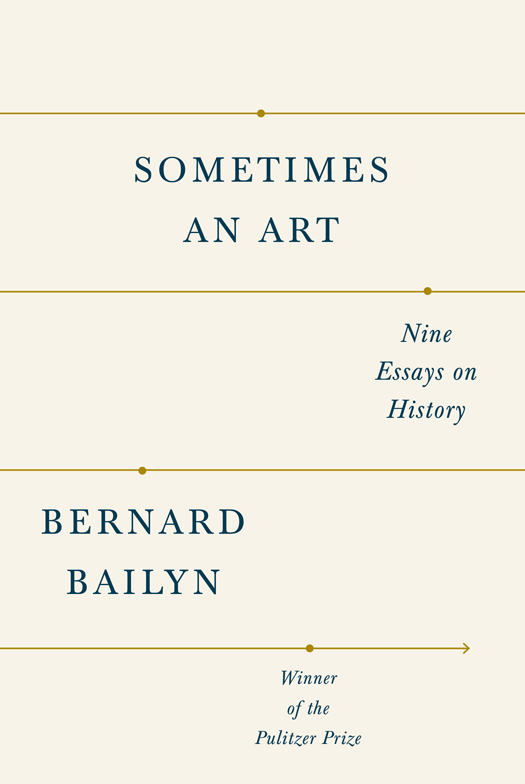

ALSO BY BERNARD BAILYN

The New England Merchants in the Seventeenth Century

Education in the Forming of American Society

The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution

The Origins of American Politics

The Ordeal of Thomas Hutchinson

The Peopling of British North America: An Introduction

Voyagers to the West: A Passage in the Peopling of America on the Eve of the Revolution

Faces of Revolution: Personalities and Themes in the Struggle for American Independence

On the Teaching and Writing of History

To Begin the World Anew: The Genius and Ambiguities of the American Founders

Atlantic History: Concept and Contours

The Barbarous Years: The Peopling of British North America: The Conflict of Civilizations, 16001675

THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK

PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF

Copyright 2015 by Bernard Bailyn

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Random House LLC, New York, and distributed in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto, Penguin Random House companies.

www.aaknopf.com

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Random House LLC.

Original published data can be found on .

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Bailyn, Bernard.

Sometimes an art: nine essays on history /

by Bernard Bailyn. First edition.

pages cm

This is a Borzoi bookTitle page verso.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-1-101-87447-9 (hardcover) ISBN 978-1-101-87448-6 (eBook)

eBook ISBN: 978-1-101-87448-6

1. HistoryPhilosophy. 2. HistoriographyPhilosophy. 3. Great BritainColoniesHistoriography. 4. United

StatesHistoriography. I. Title.

D 16.8. B 285 2015

907.2dc23 2014022229

Jacket design by Oliver Munday

v3.1

for

R EBECCA AND D IJANA ,

J ANE AND S AVA M ARIE

Contents

PART ONE

On History and the Struggle to Get It Right

PART TWO

Peripheries of the Early British Empire

Preface

This is a volume of essays most of which might properly be described as occasional in that they were written in response to invitations on particular occasions. In each case, however, my host allowed me to write freely about the topic at hand, and beyond, at my own discretion. I took advantage of such opportunities to develop my ideas in two areas: the problems and nature of history as a craft, at times an art, and aspects of the history of the colonial peripheries of the early British empire. In both areas I have written elsewhere, but the opportunities offered by these occasions allowed me to isolate key aspects of the broader story and probe them more deeply than I could otherwise have done.

The essays are reprinted as they first appeared except for minor revisions, omissions for sharper focus and greater clarity, and the reduction of references to the immediate occasions. Identification of the place and date of the original publications and the annotation appear in the back matter. In a few cases, I have added to the endnotes, in brackets, brief comments on how the subject has developed in the years that followed the appearance of the essays.

B.B.

PART ONE

On History and the Struggle to Get It Right

1

Considering the Slave Trade

History and Memory

I have been wondering about some way to express the importance of the Du Bois Institute slave trade database. Perhaps by analogy. Astronomers knew of the vast range of cosmic phenomena before the Hubble Space Telescope existed, but that extraordinarily perceptive eye, coursing freely above the earths atmosphere, has led to a degree of precision and a breadth of vision never dreamed of before and has revealed, and continues to reveal, not only new information but also new questions never broached before.

So the Du Bois slave trade database, with its tracings of 27,233 Atlantic slave trade voyages, three-quarters of which succeeded in disembarking slaves in the Americas, representing more than two-thirds of all Atlantic slave voyages, has made possible a precision and breadth of documentation in the history of the African diaspora no one had thought possible before and raises a host of new questions.

And also, it must be said, the database suffered glitches in its development not unlike those that afflicted the space telescope. Just as the Hubbles lens proved faulty and had to be repaired before it had the expected clarity, so the CD-ROM on which the slave trade data were first inscribed needed months, even years, of adjustment and correction before it reached the state of accuracy and procedural clarity it now has. At its first public appearance, at Harvards Atlantic History Workshop in April 1998, the CD-ROM itself could not be used at all, since it was still being cobbled together somewhere in Colorado, and so for that initial public performance the resourceful authors of the database had to funnel the data through an SPSS program, the relation of which to the non-performing CD-ROM only they understood. Nevertheless, the news, or some of it, came through that computerized squint clearly enough. The sheer scope and comprehensiveness of the database became vivid even then. Now the updated, computerized compilation, with its data susceptible of subtle analysis, is publicly available. While the information it contains is not complete, as the compilers candidly explain (it is, for example, fuller on the British data than on the Portuguese, stronger on the eighteenth century than on the seventeenth), it is yet a record so full, so flexible in its manipulation, and so precise in what it contains that the whole subject, not only of the trade in slaves but slavery itselfits African origins, its demography and ethnography, its economy, its politics, and its role in the development of the Western Hemispherehas been transformed. The exploitation of this resource has just begun, and as the authors show time and again, there are as yet as many questions as answers.

What strikes one first in reading the papers drawn from the database is the sheer force of numbers. I recall the first crude effort at such quantification many years agoit was merely punch-card tabulationsand I marvel at how sophisticated the numerical calculations can be and at what can now be perceived just by assembling the numbers.

For numbers (if I may put it this way) count. There is much that numbers alone, sheer quantities, can reveal.

It matters that the overall magnitude of the African diaspora is now quite definitely known: that, as David Eltis explains, it is a fact that eleven million Africans were forcibly carried abroad, more than nine million of them to the Americas. It mattersit stretches the imagination to visualizethat at the height of the British slave trade, in the 1790s, one large slave vessel left England for Africa every other day. It matters that slave rebellions occurred on approximately 10 percent of all slave ships, that 10 percent of the slaves on such voyages were killed in the insurrections (which totals one hundred thousand deaths, 15001867), and that the fear of insurrection increased shipboard staffing and other expenses on the Middle Passage by 18 percent, costs that if invested in enlarged shipments would have led to the enslavement of one million more Africans than were actually forced into the system over the course of the long eighteenth century. It matters that the incidence of revolts did not increase with the decline in crew size, hence that slave-centered factors determined the uprisings. It matters that shore-based attacks on European slave ships were twenty times more likely in the Senegal and Gambia River areas than elsewhere in Atlantic Africa. It matters that shipboard mortality (only 50 percent of all slave deathsthe rest occurred in Africa or at embarkation) did