Contents

Guide

Page List

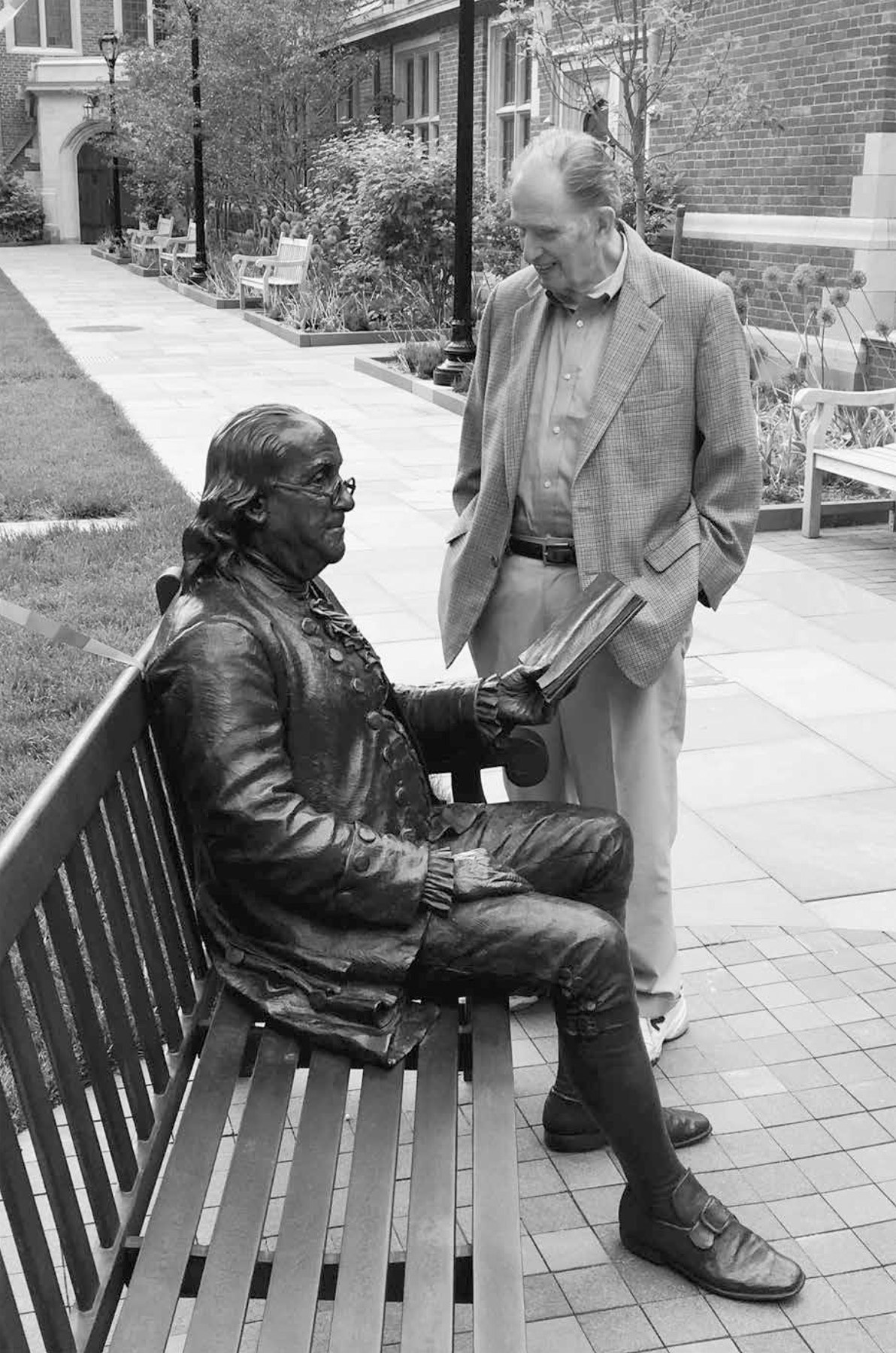

The author, with friend, 2018.

Illuminating History

A RETROSPECTIVE OF SEVEN DECADES

BERNARD BAILYN

To Lotte

Beloved companion

Who has been with me through all of this

And so much more

Its her book

Contents

Illuminating History

I saiah Berlin was wrong in his entertaining game of classifying writers and thinkers into hedgehogs, who focus on one great theme, and foxes, who study and write about many themes and see the world though many lenseswrong at least as far as historians are concerned. Many, like me, are both. Repeatedly I have been involved deeply and at length in a single absorbing subject, then have moved on to another, but touching, as I go along, smaller interests that come and go. Diverse as my interests have been, however, they reflect my intention in studying history that I had decided on in the chaotic months that followed my discharge from the army in June 1946. I had had much time in the army to think about what I might dothree and a half years, as I went through various army assignments, a year longer than the time I had had as an undergraduate.

But the story really begins further back than that. In retrospect it seems to me that my education began in an addiction I had somehow acquired to reading. By the time I entered high school I had been reading everything I could get hold of. Much of what I read I knew was over my head, but I read on anyway. I remember going through a series of illustrated classic adventure books by James Fenimore Cooper, Jules Verne, Walter Scott, and Robert Louis Stevenson, then drifted on to Dickens, though only Barnaby Rudge, a novel of the Gordon riots of 1780 and mob violence against Catholics, I can still clearly remember. My parents were complicit in this addiction, and they had an expert to advise them. Hartfords biggest and best bookstore, which once had sold books to Mark Twain, was then owned by a friend of theirs, Israel Witkower, an migr from Vienna.

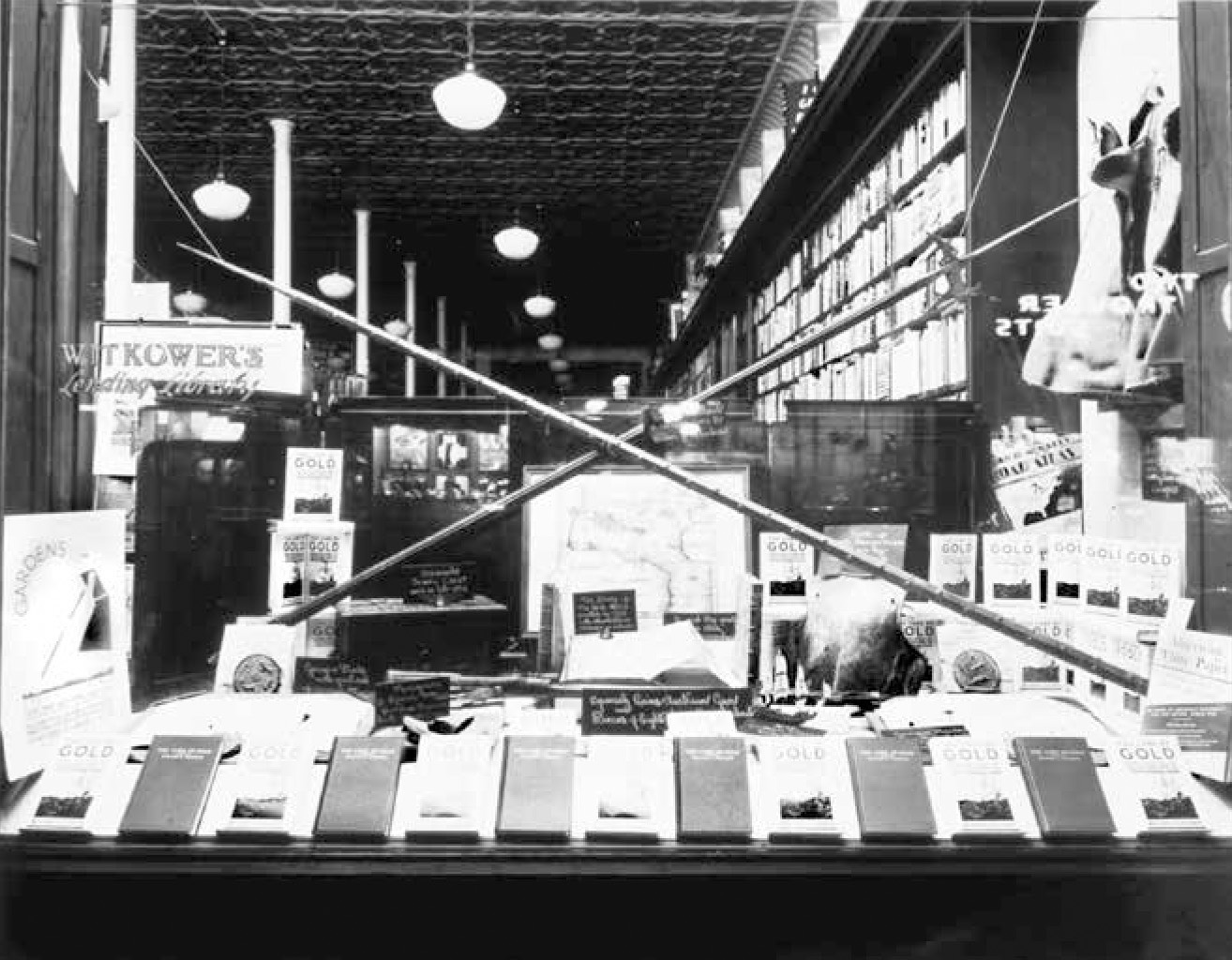

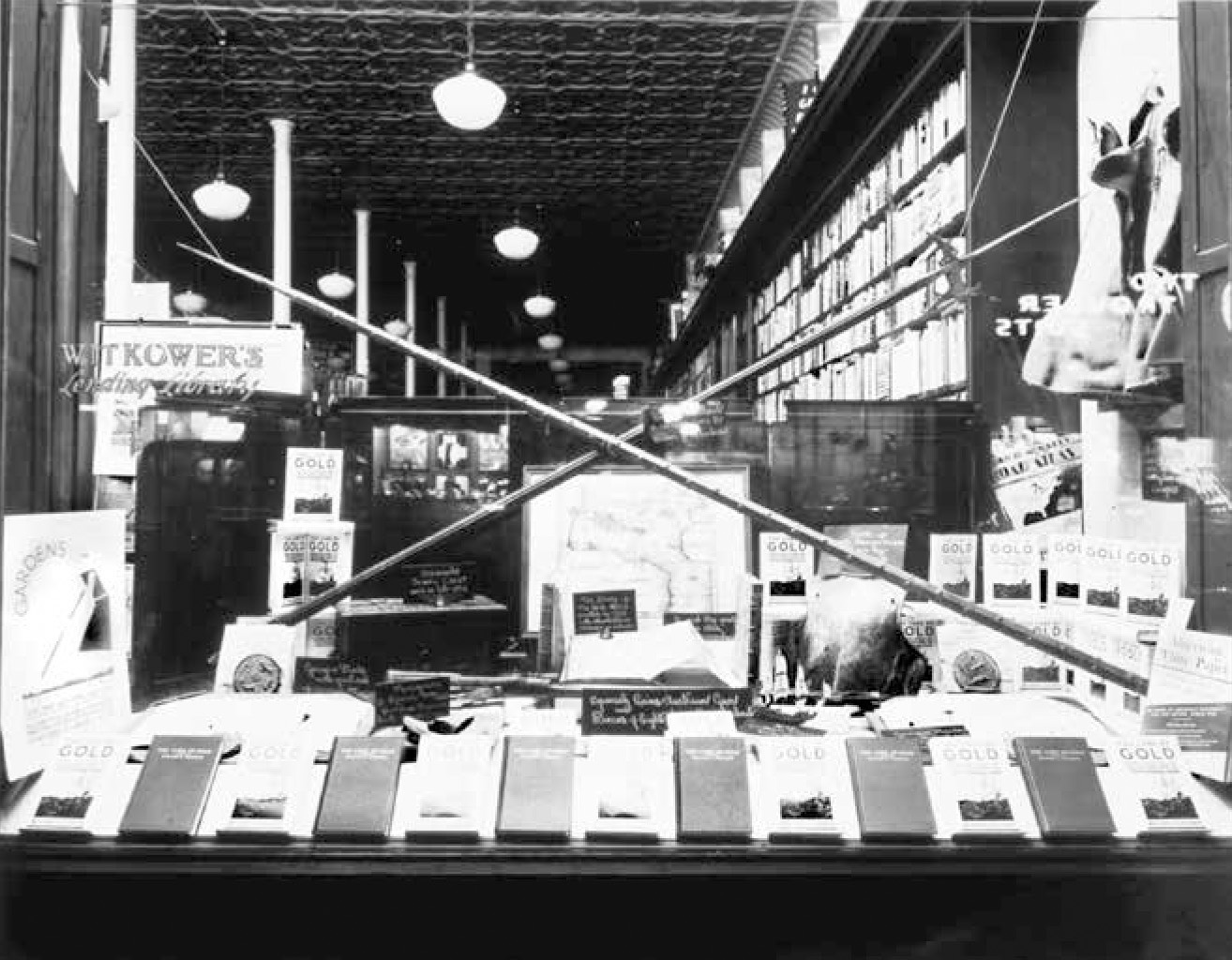

Witkowers Bookstore, 1940. The window displays copies of William B. Goodwins The Story of the New World and weapons related to the Spanish conquest.

He knew about books of all kinds, in several languages, and visiting his store, with its deep central corridor crowded with books, its alcoves, and its jumbled bargain basement, was an adventure. Occasionally through him or his son, I would receive things to read. The main gift that I can recall was given by my parents on my thirteenth birthday. It was a six-volume set of Kiplings writings. I read it all, but with much confusion, since I had no idea of the Raj or of Kiplings world views or of many of the specific references to places and events, especially in the short stories. I still have that set of books, each volume dated by me: October 1935. Somewhat later, for some reason I cant recall, I got into Eugene ONeills plays, one of which affected me profoundly.

History was of no special interest, but I recall two books, besides Barnaby Rudge, that I read before high school and that I later realized were historical in essence. I read and reread them, and I never forgot them. One was a big coffee-table book with a deeply embossed purple cover, published, I think by the Colliers magazine company, largely consisting of close-up photos of the great men and events of the early twentieth century. The pages were printed in the brownish, rotogravure process, but to me they were vivid, and the commentary was readable. The faces of the presidents and other celebrities were intriguing. But it was the battle scenes of World War I that mainly gripped my imagination, and of them, the scenes of the gas attacks at Passchendaele were the most gripping. I can still recall the ominous fog surrounding the men hiding in trenches and the trails of blinded men marching in a row. Some stared at the reader through hideous, wide-eyed gas masks that made them look like wildly glaring sea monsters. The comments were innocuous, but the scenes were fearful and unforgettable.

The other book of those pre-high-school years that was so memorable and implicitly historical contained a series of comparisons on facing pages of towns in England and in New England that bore the same names. Thus there were photos with comment on the towns of Biddeford, Devon, and Biddeford, Maine; of Bath, Somerset, and Bath, Maine; of Portsmouth, Hampshire, and Portsmouth, New Hampshire; of Newhaven, Sussex, and New Haven, Connecticut; and of Hertford, Hertfordshire, and my own town, Hartford, Connecticut. It was only later that I would understand that these were mainly towns of Englands West Country and south coast, and why their names would have carried over to New England. But it was enough for me, then, to search for the similarities and differences of these towns on either side of the Atlantic, and to puzzle about how that could have come about.

By the time I reached Hall High School in West Hartford, I was a compulsive reader, and of that affliction I have never been cured. In the high-school years I tried everything at least once, from acting in the school plays (at which I was at least not completely embarrassing) to sports of all kinds (at which I was totally embarrassing). The schools curriculum was traditional, but the teachers I knew best were excellent. In math, unfortunately, only algebra vaguely interested me, but in French I galloped ahead, to disaster. For some reason I had convinced myself that my pronunciation of the French language was good if not excellent, and so I entered the Connecticut High School French Pronunciation contest (a state program I now cannot believe could ever have existed) and to the rage of the head of my schools French department, I came in last. Years later I recalled his outrage when in a Paris caf I got into a debate with a fierce young Maoist (I was told he later became a banker). The cafs patrons were much amused, not about the debate but about my French, which was perhaps more or less fluent, but to listeners it sounded like some lost dialect of Appalachia.

But I flourished in two of the schools major programs. The two or three years of Latin I took, I enjoyedwhether because the rule-bound declensions and conjugations seemed so neatly logical, even when irregular, or whether in what I could actually read in Latin, I sensed in some small way the drama of the lives of those who had spoken the language. For whatever reason, I liked the Latin I studied and profited by it. But it was in English that I found my footing, largely the result of having two extraordinary teachers. One was Alfred A. Wright, then an elderly man soon to retire, who for years had refined his teaching of English grammar and in 1935 had published the fruit of his lifes work, Words in Action: A Study of the Sentence. A disciplinarian, he led us through the book chapter by chapter and tested us again and again with questions of increasing complexity. I recently went over Harvards copy of the book and was impressed with how elementary the beginning was and how complex the concluding chapters. It was a schoolbook, not a reference work, designed for teachers and students, but rigorous and clear throughout.