In accordance with the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, the scanning, uploading, and electronic sharing of any part of this book without the permission of the publisher constitute unlawful piracy and theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), prior written permission must be obtained by contacting the publisher at permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

I m only alive because a war dragged on too long.

My great-grandmother Charlotte Ann was born in Lancashire, England, in 1887. She worked as a weaver in the cotton mills, where she met a man named John Ethelbert Margerison. They married in 1911 and had two children, Sally and Mary.

In 1914, World War I broke out and John joined the Royal Field Artillery. In his poem MCMXIV, Philip Larkin wrote about the husbands heading off to the front with an innocence long since vanished: the men / Leaving the gardens tidy, / The thousands of marriages, / Lasting a little while longer.

The fighting on the western front quickly descended into stalemate. Trenches stretched for hundreds of miles across France and Belgium like distended varicose veins. Despite the military deadlock, both sides refused to make peace. Inspired by dreams of expansion and hatred of the enemy, the belligerents dismissed any idea of negotiating.

And so the war went on. With new technologies like machine guns and high-explosive shells, the combatants learned how to kill but not how to win. As poet Carol Ann Duffy has written, The frozen, foreign fields were acres of pain.

In February 1916, the Germans struck at the French fortress of Verdun but were halted by desperate resistance. They shall not pass. The ten-month storm of steel produced a collective tally of nearly one million dead and injured. In July 1916, the British attacked the German lines at the Somme River in northern France with a ferocious bombardment that was heard in London, 160 miles away. But the fearsome cavalcade failed to break the German defenses, and the British army suffered sixty thousand casualties on the first day of the battle. Still there were no peace negotiations.

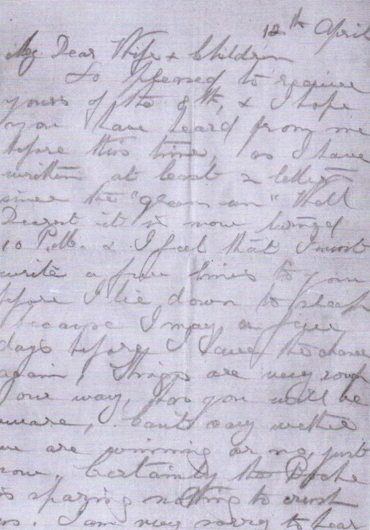

John and Charlotte Ann Margerison (Authors collection)

And so the war went on. In 1917, the British assault on Passchendaele in Flanders bogged down in a wretched hell of mud and death. Hundreds of thousands of casualties were incurred for the capture of just five miles. British reinforcements shambled up past the guns with dragging steps and the expressions of men who knew they were going to certain death, one veteran wrote. In sullen silence they filed past one by one to the sacrifice.

Unlike many of his Lancashire pals, John Margerison was still alive. If the belligerents had brokered a truce in 1914, 1915, 1916, or 1917, he would have returned home to Charlotte Ann. But any hope for an armistice was ground into dust as the combatants strove for a decisive victory to justify their terrible loss.

And so the war went on. In 1917, the United States entered the campaign on the side of Britain and France. The following year, in March 1918, Germany gambled everything on a massive spring offensive to win the war before American troops arrived in strength.

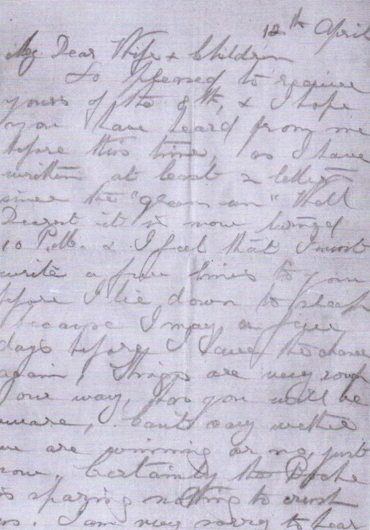

On April 12, 1918, John wrote to Charlotte Ann, scribbling in pencil on three pieces of paper. It was almost ten oclock at night: I feel that I must write a few lines to you before I lie down to sleep. It might be a few days before I have the chance again. The German attack was brutal. Things are very rough our way, as you will be aware, cant say whether we are winning or not, just now. Certainly the Boche is sparing nothing to crush us. But John was comforted by thoughts of home. I am still living in hope for the time to come when we shall be united again and war shall be no more.

Four days later, John was killed in action. He was thirty-three. According to a British officer, a team of horses which he was driving was hit by an enemy shell and death was instantaneous.

The Margerisons were just one of ten million European families ripped apart by the storm of war. But death sometimes brings life in its wake. Charlotte Ann eventually remarried. Her new husband was a much older man, a widower named William Tracy. She brought her two children, Sally and Mary, into the marriage. He came with six kids. And they had two more children togetherone of whom was my grandfather, John Tracy. Without the shell blast that killed John Margerison in 1918, my grandfather would almost certainly never have been born.

World War I continued long past the point when the combatants should have rationally ended the fighting. The countries that lost the war were left crippled and embittered. Even the winners were physically and psychologically traumatized. The protracted conflict sowed fetid seeds of revolution and revenge that yielded a second global cataclysm just two decades later.

John Margerisons last letter, April 12, 1918 (Authors collection)

Today, as we see in Afghanistan, were little closer to solving the puzzle of ending a stalemated or failing war. To learn how to forge a path out of conflict, we must sometimes analyze war with a dispassionate eye. But we should always remember that beneath the abstract language of strategy lie families like the Margerisons.

In his last letter in 1918, John sent a special message to his five-year-old daughter: Tell our Sally father sends his love to her and that I am expecting to hear of her being good at school. In 2015, Sally turned 102 years old. Shes one of the last remaining strands connecting our generation to the Great War.

A t 9:44 p.m. on July 27, 1953, Private First Class Harold B. Smith had just sixteen more minutes of the Korean War to survive before the cease-fire came into effect at 10:00 p.m. You can imagine this twenty-one-year old marine from Illinois, out on combat patrol that evening, looking at his watch. Smith didnt have to be in Korea. He had already served his time in the Philippines. But he volunteered for the fight. He also didnt have to be on patrol that evening. But he offered to take the place of another guy who went out two nights before.

Suddenly, Smith tripped a land mine and was fatally wounded. I was looking directly at him when I heard the pop and saw the flash, recalled a fellow marine. The explosion was followed by a terrible scream that was heard probably a mile away.

Twenty-two years later, on April 29, 1975, Lance Corporal Darwin Judge and Corporal Charles McMahon were marine guards near an air base outside Saigon in South Vietnam. Judge was an Iowa boy and a gifted woodworker. He once built a grandfather clock that still kept time decades later. His buddy,

The two men had only been in South Vietnam for a few days. They were part of a small U.S. security force that remained after the main American withdrawal in 1973. McMahon and Judge arrived just in time for the military endgame, as North Vietnamese troops bore down on Saigon. McMahon mailed his mother a postcard: After this duty, they may send us home for a while. Ill try to write when I have time and dont worry Ma!!!!

![Fawcett - How to lose the Civil War : [military mistakes of the War between the States]](/uploads/posts/book/92687/thumbs/fawcett-how-to-lose-the-civil-war-military.jpg)