Table of Contents

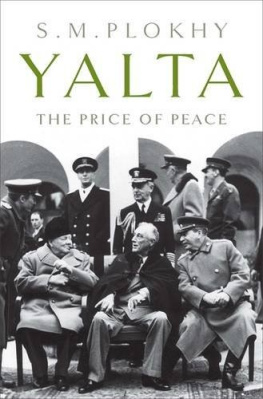

ALSO BY S. M. PLOKHY

Ukraine and Russia: Representations of the Past

The Origins of the Slavic Nations: Premodern Identities

in Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus

Unmaking Imperial Russia: Mykhailo Hrushevsky

and the Writing of Ukrainian History

Tsars and Cossacks: A Study in Iconography

The Cossacks and Religion in Early Modern Ukraine

VIKING

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, U.S.A. Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3 (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.) Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England Penguin Ireland, 25 St. Stephens Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd) Penguin Books Australia Ltd, 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd) Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi-110 017, India Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, North Shore 0632, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd) Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

First published in 2010 by Viking Penguin, a member of Penguin Group (USA) Inc.

Copyright Serhii Plokhy, 2010

All rights reserved

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Plokhy, Serhii, 1957-

Yalta : the price of peace / S.M. Plokhy.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

eISBN : 978-1-101-18992-4

1. Yalta Conference (1945) 2. World War, 1939-1945Diplomatic history. 3. World War, 1939-1945Peace.

4. World politics1945-1989. I. Title.

D734.C726 2010

940.5314dc22 2009026833

Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book via the Internet or via any other means without the permission of the publisher is illegal and punishable by law. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrightable materials. Your support of the authors rights is appreciated.

http://us.penguingroup.com

For

ANDRII

and

OLESIA

The work, my friends, is peace. More than an end of this waran end to the beginnings of all wars.

INTRODUCTION

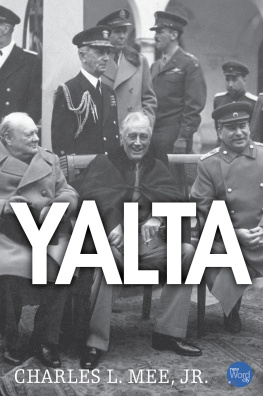

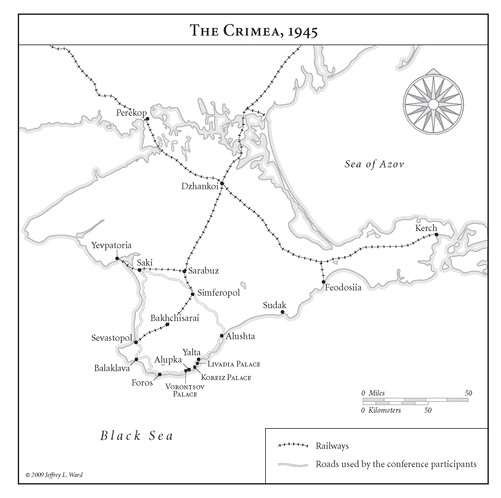

T he time and location of the meeting were among the most heavily guarded secrets of the whole war. On the evening of February 3, 1945, under cover of darkness, a fleet of Packards brought the two most powerful leaders of the democratic world, Franklin Delano Roosevelt and Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill, to their destinationa group of villas formerly owned by the Russian tsar and prominent aristocrats near the Black Sea resort of Yalta. They called themselves the Argonauts, a reference to the ancient warriors who had traveled to the Black Sea coast to recover the Golden Fleece from a dragon who never slept. Their prize was a settlement to the war that had engulfed the world; their dragon was their host, Joseph Stalin, once a promising Georgian poet and now a ruthless dictator.

Together the three men conducted the most secretive peace conference of the modern era. They moved armies of millions and dispensed victors justice as they saw fit, deciding the fate of nations and sending millions of refugees east and west because they believed it would promote a lasting peace. They created an institution to guard that peace and the interests of the victors. They left Yalta satisfied but anxious. Behind them lay thirty years ravaged by two world wars that had cost tens of millions of human lives. Before them was the uncertainty of the postwar world.

The contest of geopolitical aspirations, the clash of egos and value systems, and the jockeying for power among the most astute negotiators their nations could produce all played out in eight days at Yalta in February 1945. The three leaders wondered about one anothers trustworthiness and readiness to compromise. Would the alumni of the best private schools of Britain and America reach an understanding with the son of a Georgian shoemaker who had dropped out of an Orthodox seminary? Would the two democratically elected leaders know how to handle the godfather of the Gulag? The conference confronted its participants with endless moral dilemmas. It was an emotional roller coaster that involved not only the leaders of the Grand Alliance but also their various subordinates, who fought for their countries interests and for the favor of their masters.

Within a few short years of the end of the conference, the high hopes of its authors were dashed, their decisions condemned by friend and foe alike. The surviving participants went on the defensive or preferred to forget their involvement. Feelings of disappointment and regret dominated on both sides of the Cold War divide. Yalta became a symbol of lost opportunity, however differently perceived. In the West, it came to be regarded as a milestone on the road to the lost peace, to cite a 1950s headline in Time magazine. In the mainstream discourse of the McCarthy era, the word Yalta became a synonym for betrayal of freedom and the appeasement of world communism.

Who was responsible? That became a central question with the onset of the Cold War in the late 1940s, when the two sides blamed each other. There were also heated domestic debates. In the United States the decisions taken at Yalta divided Republicans and Democrats. President Roosevelt and his advisers were accused not only of selling out Eastern Europe and China to Stalin but also of promoting communism at home. The highly publicized trial of Alger Hiss, a member of the U.S. delegation at Yalta who was accused of spying for the USSR, raised the temperature of the debate. Interviewed after his retirement for a book about his life, General George C. Marshall declined to make any substantive comment about his role at Yalta, certain that whatever he said would be turned against him.