The Lamp of Experience

This book is published by Liberty Fund, Inc., a foundation established to encourage study of the ideal of a society of free and responsible individuals.

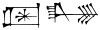

The cuneiform inscription that serves as our logo and as a design element in Liberty Fund books is the earliest-known written appearance of the word freedom ( amagi ), or liberty. It is taken from a clay document written about 2300 B.C. in the Sumerian city-state of Lagash.

1965, 1998 by Liberty Fund, Inc. First published in 1965 by the University of North Carolina Press.

This eBook edition published in 2011.

eBook ISBN: Kindle 978-1-61487-006-7

www.libertyfund.org

For Douglass

Contents

Much has happened in the more than thirty years that have passed since The Lamp of Experience was first published by the Institute of Early American History in 1965. Many who helped shape that volume have passed onnotably, Douglass Adair (to whom The Lamp of Experience was properly dedicated), Lyman Butterfield, Julian Boyd, Dumas Malone, Millicent Sowerby, Edwin Wolf II, and John H. Powell. It is a depressingly long list. But this new edition allows for the confirmation of earlier acknowledgments and obligations and also permits some brief reflections on the strange history of a book about history.

Born in Australia (his parents were there at the time), the author was educated in England (European diplomatic history with the late William Medlicott) and secured his graduate degrees in Williamsburg and Baltimore. In Williamsburg, at the College of William and Mary, a young assistant professor named Adair introduced a much younger exchange student named Colbourn to Thomas Jefferson and took seeming delight in asking questions only the questioner could answer. Certainly migration to Baltimore was not an immediate solution: Colbourns arrival at The Johns Hopkins University in 1949 coincided with his discovery that the Hopkins colonialist, Charles Barker, had decided to abandon his study of the American Revolution for Henry George (1955), also a conservative revolutionary to be sure. But the late Charles Barker was a generous spirit who readily agreed to the creation of a very informal advisory committee for his errant graduate student, which soon included Douglass Adair, Dumas Malone, Lyman Butterfield, and Adairs very scholarly friend, Caroline Robbins. All were generous with their time and all knew Jefferson rather well. The outcome, spurred by the incentive of reemployment at Penn State in 1953, was a doctoral dissertation on Thomas Jeffersons use of history. In turn this dissertation generated a paper given at the American Historical Association convention in 1955, which in turn led to an article in the 1958 William and Mary Quarterly.

What next? Lyman Butterfield thought the authors approach to Jefferson had promise but needed substantial expansion. And so the subject of Thomas Jefferson provided the material for chapter 8 and the seed for the further inquiry that became The Lamp of Experience. Such growth owed much to the encouragement provided by Caroline Robbins, who allowed the author a summer in her extraordinary private library. Shelf after shelf of the writings of her seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Commonwealthmen illustrated the relevance of Englands Real Whigs for the leaders of the American Revolution. Frequent visits to the Library of Congresss Rare Book Room and a year combing the shelves of the Library Company of Philadelphia reinforced that message.

Thus far the emergence of The Lamp of Experience was far from unusual except for the time taken by its author in writing it. Perhaps his colleagues were too patient. Certainly there were other studies under way and other books already published that advanced the understanding of the intellectual origins of the American Revolution. Some books seem to await the appearance of other books before they take shape. This is particularly true for our understanding of the era of the Revolution, for which 1943 emerges as a seminal historiographical turning point. In the midst of World War II the United States had good reason to celebrate the bicentennial of the birth of Thomas Jefferson and laid plans for the publication of all the available papers of that great spokesman for democracy. Begun by Julian Boyd and Lyman Butterfield, this ambitious project has outlived both men. Butterfield, to be sure, deserted Jefferson for the Adams family and editing on a less comprehensive scale. He did, however, live to complete his Diary and Autobiography of John Adams (1961) and his Adams Family Correspondence (1963) and to see similar projects emerge as a tribute to most of the Founding Fathers.

Plans were also laid for a unique catalog of the magnificent private library Jefferson sold to the Congress in 1815. In charge of this noble enterprise was a battle-axe of an Englishwoman, Millicent Sowerby, who, like her one-time colleague, Ed Wolf, was a rare-book specialist. Wolf later took charge of the Library Company of Philadelphia and made Benjamin Franklins collection into an available and very special resource for students of eighteenth-century America. Millicent Sowerby pursued her task with deliberate speed (195259) but rewarded her impatient admirers with so much more than an inventory of Jeffersons greatest library: she told us when he acquired his books and, if possible, what he thought of them. This was, wrote Douglass Adair in his William and Mary Quarterly review, a bio-bibliography, and a marvelous guide to the intellectual world of Jefferson.

Caroline Robbins was the other willful Englishwoman who made very special contributions to our understanding of the intellectual world of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Sometime Chair at Bryn Mawr College, she is still justly venerated for her pathfinding The Eighteenth-Century Commonwealthman (1959), dedicated to her famous brother. Both The Lamp and Bernard Bailyns Ideological Origins of the American Revolution appeared six years later, and both were enormously indebted to Robbins and her writings on the Commonwealthmen. Even Jonathan Clark, whose interpretations of the material do not always agree with those of Robbins, concedes in The Language of Liberty (1994) the meticulous scholarship exhibited by his compatriot. Well he might.

But 1943 offered more than a new commitment to the American past in the form of plans for the publication of the Founding Fathers papers and the identification of their books. It was also the year that saw several additional happenings of historical consequence: Columbia University published Adrienne Kochs doctoral dissertation, The Philosophy of Thomas Jefferson; Merle Curti successfully made the case for the larger world of ideas in his The Growth of American Democratic Thought; and his friend Ralph Henry Gabriel signed off on the extraordinary doctoral dissertation submitted by the young Douglass Adair at Yale, The Intellectual Origins of Jeffersonian Democracy: Republicans, the Class Struggle, and the Virtuous Farmer. Curtis book remains very much in print, but, strangely, the Adair manuscript long remained just that, a manuscript. Strangely, because the list of interlibrary borrowers could well be mistaken for a Whos Who among early American historians. Indeed, Adair offered that as his excuse: Everyone who should read the book has already borrowed it from Yale. Instead of creating more reasons for celebrating 1943, such as revising his dissertation for publication, Adair devoted more and more of his considerable energies to his relationship with The College of William and Mary as cosponsor of the William and Mary Quarterly (from 1946 to 1955). This was an association that brought fame to both Adair and the college.

Next page