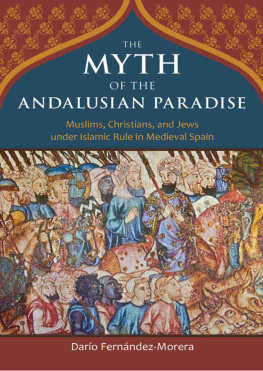

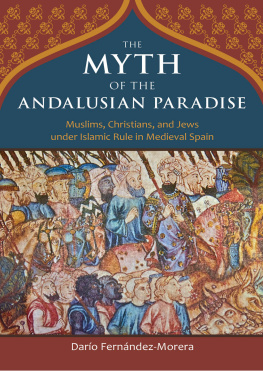

The Myth of the Andalusian Paradise

Muslims, Christians, and Jews under Islamic Rule in Medieval Spain

Daro Fernndez-Morera

Wilmington, Delaware

Muslim horsemen and their black slave warriors herding Christian prisoners and their cattle: from the Cantigas de Santa Mara, thirteenth-century illuminated manuscript

Dedico este libro a los Fernndez-Morera y a los que ayudaron a criarme: Daro (El Gran Dary), mi padre, el mejor mago que ha dado Cuba; su ayudante la bella Ester (Sonia), mi querida madre; mi hijo Brent (El rbol); mi prima Rosa Mara (Pety); mi to-abuelo Gomer (Gordo), conocedor de Voltaire y de la poesa de Victor Hugo y de Rubn Daro, y quien tanto me ayud en mi adolescencia; mi abuelo Oscar, el pintor de nuestra ciudad natal, Sancti-Spiritus, y el mejor pintor que ha dado Cuba; mi ta Selmira, pintora y profesora, quien siempre insisti en que me hiciera de una profesin, porque de pintor y ajedrecista te vas a morir de hambre; mi to Plinio (Cuco), el cazador, el primero que me ense el uso de las armas; mi ta Flrida, lectora voraz, siempre elegante; mi to-abuelo Higinio (El intelectual), periodista y editor de la revista literaria Hero; mi to-abuelo el finsimo poeta y tambin editor de Hero, Anastasio (El Poeta); mi to-abuelo Jacinto (el Jacintico), admirador de Herodes; mi bisabuelo Jacinto Gomer Fernndez-Morera, fundador de Hero, poeta de corte clsico, maestro, y crtico valiente y lcido; mis Padrinos Federico e Iluminada del Castillo, quienes tambin ayudaron a criarme; y mi querida Mara Rojas, gran practicante de la Santera, quien tanto me quiso y cuid en mi niez.

Ma, sendo lintento mio scrivere cosa utile a chi la intende, mi parso pi conveniente andare drieto alla verit effettuale della cosa, che alla immaginazione di essa.

Niccol Machiavelli, Il Principe, capitolo XV

Contents

Introduction

On the intellectual level, Islam played an important role in the development of Western European civilization by passing on both the philosophy of Aristotle and its own scientific, technological, and philosophical tradition. Religious tolerance remained a part of Islamic law, although its application varied with social, political, and economic circumstances.

Bert F. Breiner and Christian W. Troll, Christianity and Islam, in The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Modern Islamic World, ed. John L. Esposito (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009)

[In the Middle Ages there emerged] two Europesone [Muslim Europe] secure in its defenses, religiously tolerant, and maturing in cultural and scientific sophistication; the other [Christian Europe] an arena of unceasing warfare in which superstition passed for religion and the flame of knowledge sputtered weakly.

David Levering Lewis, two-time Pulitzer Prize winner and Julius Silver Professor of History at New York University, Gods Crucible: Islam and the Making of Europe, 5701215 (New York: W. W. Norton, 2008), 335

Muslim rulers of the past were far more tolerant of people of other faiths than were Christian ones. For example, al-Andaluss multi-cultural, multi-religious states ruled by Muslims gave way to a Christian regime that was grossly intolerant even of dissident Christians, and that offered Jews and Muslims a choice only between being forcibly converted and being expelled (or worse).

Islam and the West: Never the Twain Shall Peacefully Meet? The Economist, November 15, 2001

The standard-bearers of tolerance in the early Middle Ages were far more likely to be found in Muslim lands than in Christian ones.

Tony Blair, then prime minister of Great Britain, A Battle for Global Values, Foreign Affairs, January/February 2007

This book aims to demystify Islamic Spain by questioning the widespread belief that it was a wonderful place of tolerance and convivencia of three cultures under the benevolent supervision of enlightened Muslim rulers. As the epigraphs throughout this book illustrate, the nineteenth-century romantic vision of Islamic Spain has morphed into todays mainstream academic and popular writings that celebrate al-Andalus for its multiculturalism, unity of Muslims, Christians, and Jews, diversity, and pluralism, regardless of how close such emphasis is to the facts. Some scholars of the Spanish Middle Ages have even openly declared an interest in promoting these ideas.

Demythologizing this civilization requires focusing a searching light on medieval cultural features that may seem less than savory to modern readers and that perhaps for this reason are seldom discussed. The first two chapters of this book examine how Spain was conquered and colonized by the forces of the Islamic Caliphate. Some scholars have argued that the Muslim takeover was accomplished largely through peaceful pacts; some even refuse to call it a conquest, preferring to call it a migratory wave. Other scholars argue that the conquest was carried out by force.cultural repression in all areas of life and the marginalization of certain groupsall this in the service of social control by autocratic rulers and a class of religious authorities.

The proponents of a harmonious and fruitful convivencia sometimes adduce as proof the mutual influences among Muslims and non-Muslims and their military alliances. But this argument overlooks that mutual influences, coexistence in the same territory, cooperation, military alliances and even intermarriage, and productive and fascinating artistic results frequently obtain as a matter of course in places where different cultures have been antagonisticfrom Spanish and Portuguese Latin America to British India to French Algeria to the American West to even the slaveholding American Southwithout this in any way diminishing the fact of conflict between cultures or the existence of some groups who dominate and others who are dominated. Of course there was convivencia, in this rather banal sense, between conquerors and conquered, but this cannot be considered characteristic of Islamic Spain: it is characteristic of cultural clashes between hegemonic and hegemonized groups most everywhere.

This books interpretive stance is Machiavellian, not Panglossian. Those who portray Islamic Spain as an example of peaceful coexistence frequently cite the fact that Muslim, Jewish, and Christian groups in al-Andalus sometimes lived near one another. Even when that was the case, however, such groups dwelled more often than not in their own neighborhoods. More to the point: even when individual Muslims, Jews, and Christians cooperated with one another out of convenience, necessity, mutual sympathy, or love, these three groups and their own numerous subgroups engaged for centuries in struggles for power and cultural survival, manifested in often subtle ways that should not be glossed over for the sake of modern ideals of tolerance, diversity, and convivencia.

A C ULTURE OF F ORGETTING

The Umayyad Caliphate collapsed in the eleventh century. In 1085, Alfonso VI, Christian king of Leon and Castile, captured Toledo; unlike the Franks, he knew better than to impose Catholicism on the people at the point of a sword. The spirit of tolerance that the Arabs had created survived their departure. It took nearly four more centuries to get to the religious intolerance of the Spanish Inquisition.

Kwame Anthony Appiah, Laurance S. Rockefeller University Professor of Philosophy, Princeton University, How Muslims Made Europe

Next page