Knowledge said to me, Love is madness;

Love said to me, Knowledge is estimation and presumption.

Knowledge is born a question, Love is the hidden answer;

Knowledge is Son of the Book, Love is Mother of the Book!

ALLAMA IQBAL , Ilm wa Ishq (Knowledge and Love)

It is seeing which establishes our place in the surrounding world; we explain that world with words, but words can never undo the fact that we are surrounded by it. The relation between what we see and what we know is never settled.

A book involving the admixture of Arabic, Persian, and Ottoman transliteration systems is, as I have discovered, no easy matter. The standard IJMES system, which I employ throughout this book, does not fit Ottoman transliteration well. Thus, Mehmet becomes Memed but Tr-i Hind-i Gharb (History of the West Indies) cannot be changed to the Arabic form of Trkh. Similarly, Lomn looks odd when transliterated according to the Arabic system as Luqmn. The problem is compounded by modern Turkish, which uses, for example, c for j. Thus, Cerriyyetl-niyye (Imperial Surgery) should be transliterated as Jerriyyet according to the IJMES system, but no one would be able to locate the book under that spelling. For this reason, the transliteration of Ottoman Turkish under the IJMES scheme cannot be foolproof. The case of Persian is easier. I apply the IJMES transliteration convention. Instead of the Persian spelling Iskander, for instance, I use Iskandar according to the Arabic convention. In order to preserve the narrative flow I have removed the prefix al- from the start of Arabic last names. Thus abar instead of al-abar, Mamn instead of al-Mamn, and so on. Exceptions to this are quotes and full names.

Place-names present especially complex choices: Does one list Mecca according to common practice or according to the correct transliteration of Makka? Medina or Madina? More vexing is the correct use of names for which a local equivalent has become popular. Seville versus Sevilla is a case in point. Troublesome is the spelling for the East African tribe that forms the core of chapters : Buja according to Arabic orthography or Beja according to common practice? I decided in favor of common practice. So I use Mecca, Medina, Sevilla, and Beja. I transliterate only those place-names that I judge as being not well known or without an Arabic alternativefor example, Ifrqiya, Zaghwa, and Mafza al-Buja.

In cases where usage of a word is common, I do not list it in its transliterated form (e.g., sultan not suln). Exceptions to this are references to the Qurn and adth. I also elected to not transliterate dynastic names. Outside of what falls into the domain of common practice, I chose to transliterate all Arabic, Persian, and Turkish words, names, and book titles. I may have missed a few and for this the error lies with me alone.

In short, I use a hybrid IJMES system in consultation with the method adopted by the associate editor of book 1 of the second volume of The History of Cartography, Ahmet Karamustafa, who also had to wrestle with the transliteration scheme of three different languages and the place-name dilemma and developed brilliant solutions.

All translations are my own unless otherwise noted.

Introduction

Ways of Seeing Islamic Maps

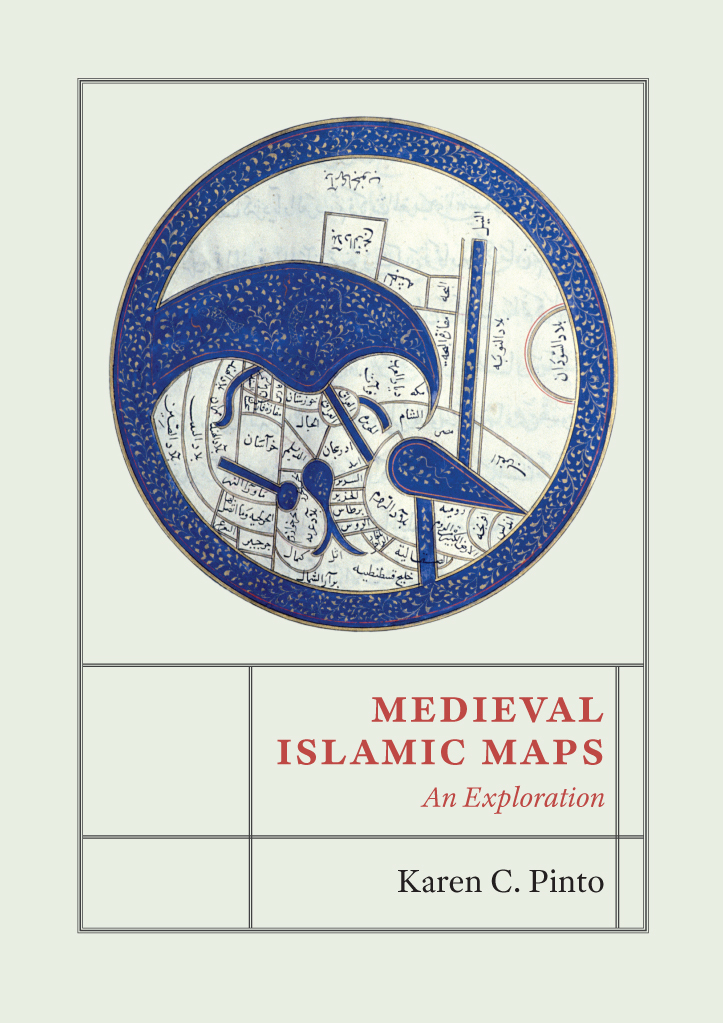

They present instead a deliberately schematic layout of the world and the regions under Islamic control.

These images employ a language of stylized forms that make them hard to recognize as maps. Scholars of Islamic science and geography often ignore and belittle these maps

Fig. 1.1. Classic KMMS world map, rat al-Ar (Picture of the World), from an abbreviated copy of al-Iakhrs Kitb al-maslik wa-al-mamlik (Book of Routes and Realms). 589 / 1193. Mediterranean. Gouache and ink on paper. Diameter 37.5 cm. Courtesy: Leiden University Libraries. Cod. Or. 3101, fols. 45.

On the surface it seems that these often elaborately illuminated nonmimetic cartographic works, employing pigments made from precious metals and stones, must have been produced for the elite literati of medieval Islamic society such as the commissioners / patrons, collectors, copyists, and high-status readers of the geographic texts within which these maps are found. This conclusion ignores the easy-to-replicate nature of these schematic images, which would have enabled students visiting the libraries of sultans, amirs, and other members of the ruling elite to transport basic versions of these carto-ideographs back to the people of their villages and far-flung areas of the Islamic world.

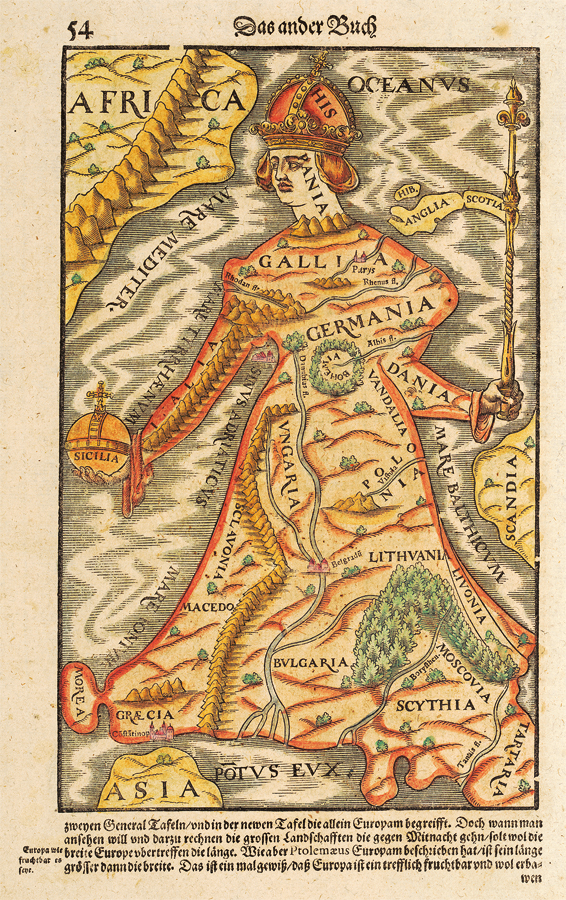

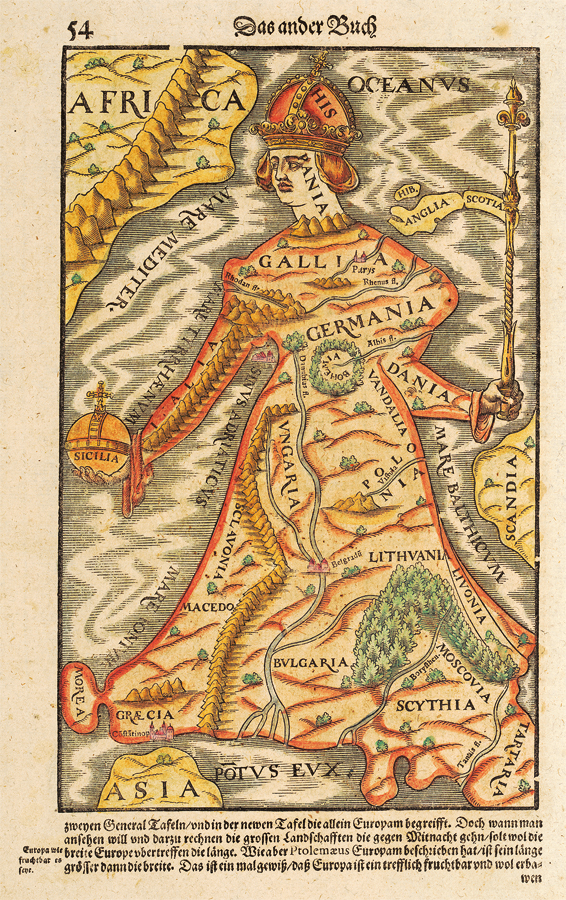

). To simply dismiss this map as an inaccurate representation of Europe and therefore an invalid source is to miss the point. It is reflective of a much deeper sociocultural, historical, and political context that needs to be read and interpreted. Are the metaphorical coastlines reflective of an emerging consciousness of European supremacy? Can they not be read as a sort of pre-colonial colonialism with Spain and Portugal leading the way, assisted by the arm of Italy and the pivotal island of Sicily on one side and by the staff of the North Sea formed by the Danes, the English, and the Scots on the other? The Mnster map demonstrates how cartography can be used to navigate the medieval and early modern imagination.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).