Maria Vaiou holds a D.Phil. in Modern History from the University of Oxford. She has taught at Saban University in Istanbul. Her research focuses on the relations between the Byzantine empire and the Muslim world.

Published in 2015 by I.B.Tauris & Co. Ltd

London New York

www.ibtauris.com

Copyright 2015 Maria Vaiou

The right of Maria Vaiou to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patent Act 1988.

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or any part thereof, may not be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Library of Middle East History 17

ISBN: 978 1 84511 652 1

A full CIP record for this book is available from the British Library

A full CIP record for this book is available from the Library of Congress

Library of Congress catalog card: available

For my son Apostolos-Pavlos

Preface

I first came across Ibn al-Farrs Rusul al-Mulk some years ago, when I was writing my D.Phil. thesis, in the library of the Oriental Institute in Oxford. I found the text that described the conduct of messengers and diplomatic relations in the Muslim world extraordinarily interesting, for it contained fascinating passages on the interaction between the Byzantines and Abbsids. I used the Rusul al-Mulk extensively in my thesis and, after receiving a grant from the British Academy and with encouragement from Jonathan Shepard and Hugh Kennedy, I proceeded to work on a translation of the text.

This book presents the first English translation of the Kitb Rusul al-Mulk (The Book of Messengers of Kings) an Arabic treatise on diplomacy attributed to Ibn al-Farr. This treatise is remarkable for three reasons. Firstly, it is the only known medieval work on the conduct of messengers and it was most probably written in the tenth century. Secondly, it is an anthology consisting of a selection of important sources. And thirdly, it legitimizes the practice of diplomacy by providing a religious basis drawn on the Qurn, and the Prophets sayings and traditions, elevating it to the level of a holy occupation.

Although the Rusul al-Mulk is atypical in many respects, it should be seen as belonging to the genre of mirrors for princes. It advises a ruler or high official on how to choose the right messenger, recommending rules of conduct for messengers. It gives an ethical dimension to the field of diplomacy, focusing on the ethical principles that should underpin the conduct of messengers. Through its insight into human psychology, the text exhibits a deep interest in the individual, who is seen as an agent capable of progress contributing to the common welfare of society. In its organization, style and purpose the Rusul al-Mulk is without precedent.

The primary aim of the present annotated translation is to make the text available to readers without Arabic and to those who have an interest in ArabByzantine diplomatic relations or Muslim diplomacy in general. It is my hope, however, that the translation will also help the book to reach the wider audience it deserves. It presents a picture of the Arabs and Byzantines not as perpetual rivals in the military field, but as civilized negotiators who could adopt and promote peaceful ways of dealing with their affairs. In addition, it shows how the Arabs perceived diplomatic conduct in the tenth century. The qualities valued in medieval Arab and Byzantine messengers are not dissimilar from those that make for successful diplomats today, and Ibn al-Farrs advice, and the examples he provides, have much contemporary interest and resonance.

Acknowledgements

This book owes a great deal to the British Academy, which through a grant enabled me to carry out this work, and to a number of individuals. I wish to thank in particular Jonathan Shepard whose firm support and encouragement helped me through the different stages of writing and publishing this book. I also would like to thank Hugh Kennedy who greatly encouraged me to publish the project. I owe thanks to the Oxford Centre for Islamic Studies for offering me a research grant in 1999 to travel to Egypt to find the manuscripts of Ibn al-Farr. I also wish to thank the staff in the department of manuscripts in the Dr al-Kutub Library in Cairo, the National Library in Cairo, and the Rare Books Library in Cairo, the director Ms Filiz agman and the staff of the Topkap Saray Library in Istanbul who facilitated my effort to obtain a copy of Ibn al-Farrs original manuscript in the summer of 2004, the monastery of the monastery of Zoodochos Pege in Istanbul for my stay in the summer of 2004, the Institute of Classical Studies in London, the Warburg Institute Library in London, the Institute of Historical Research in London, the Oriental Institute Library in Oxford, the Bodleian Library in Oxford, the School of Oriental and African Studies in London, and the staff of the Saban University Library in Istanbul. I owe a special debt to Stelios Sakellariou, but I wish also to thank His Eminence the Archbishop Gregorios of Thyateira and Great Britain, and especially Jafar Hd assn for contributing towards the preparation of the book. Finally, I wish to thank Averil Cameron, Jonathan Shepard, Julia Bray, Catherine Holmes, Geert Jan van Gelder, Peter Pormann and Muammad Farag for a number of suggestions and comments they made on drafts of parts of the text.

Note on Transliteration

The system of transliteration from Arabic is adopted from the Encyclopaedia of Islam, second edition, with the following variations that dj is replaced by j and k. by q. Arabic names that have a form generally accepted in English have been used in that form.

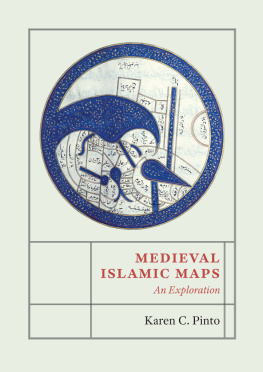

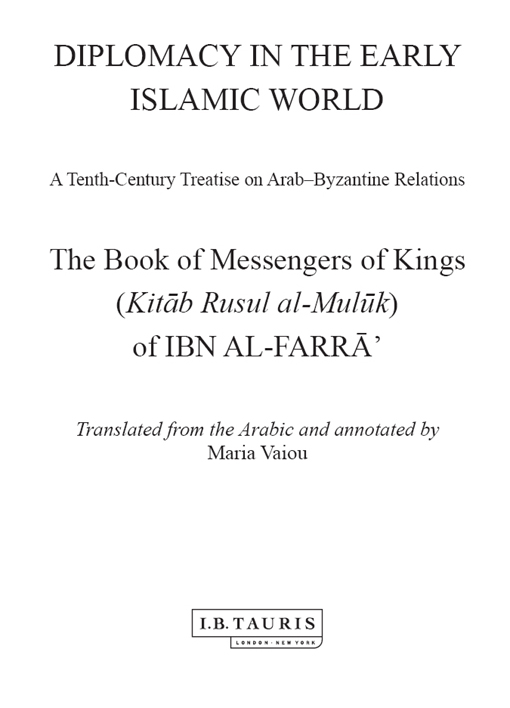

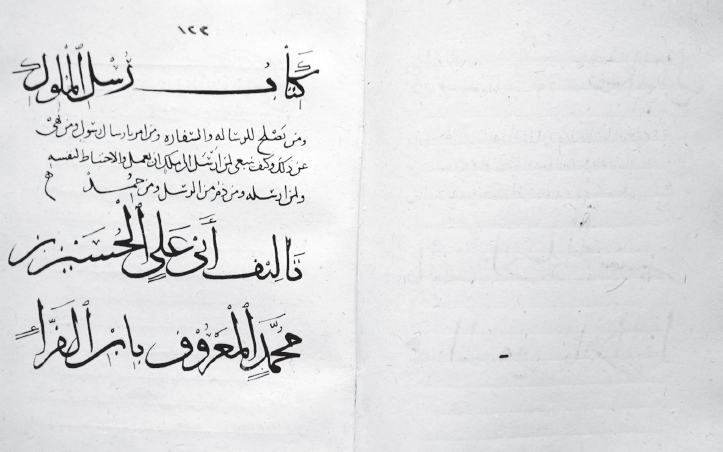

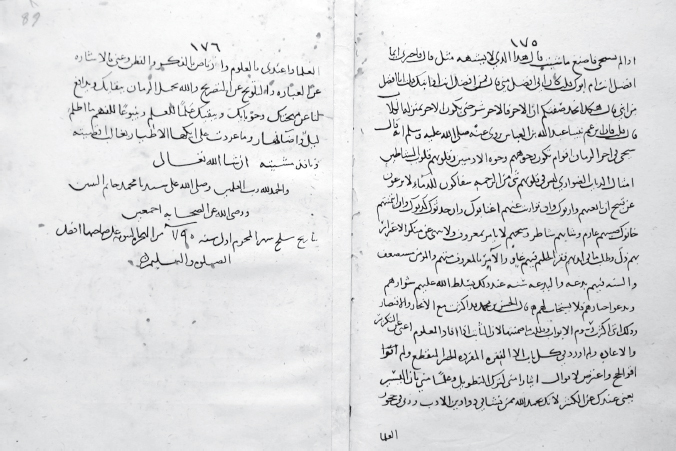

List of plates

The title page of the original text

The final two pages of the original text

List of maps

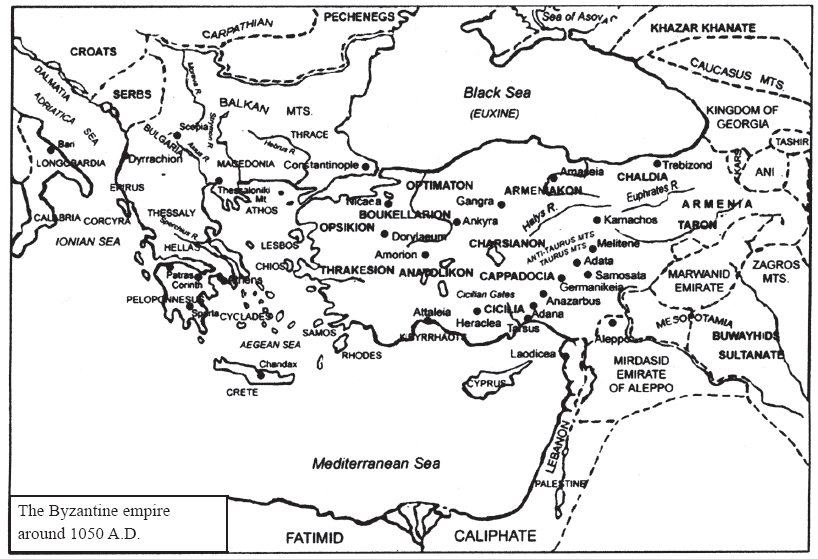

The Byzantine empire around 1050 A.D.

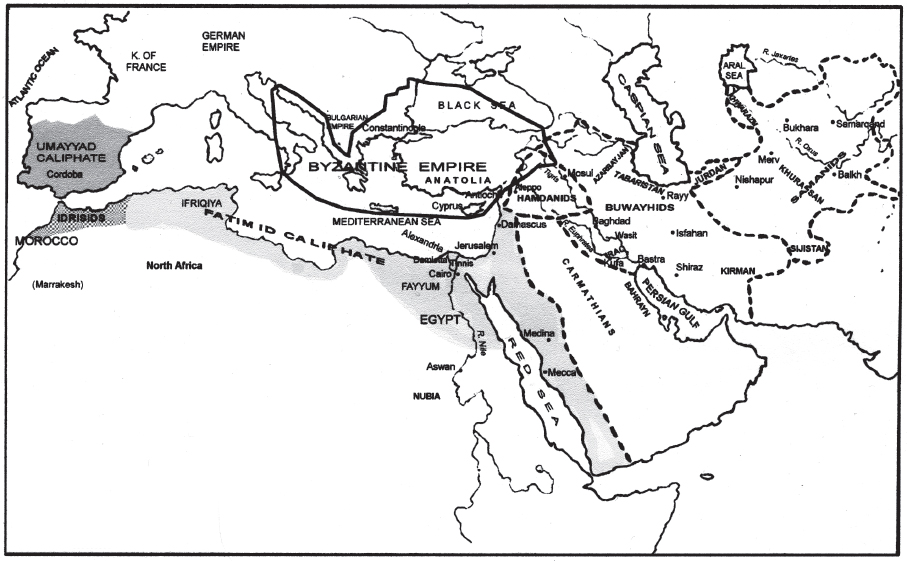

The Muslim provinces in the late tenth century

List of figures

John Syncellus gives the Arabs presents

Caliph al-Mamn sends an ambassador to emperor Theophilus

The Byzantine delegation to the Amermoumnes

The Saracen delegation to emperor Theophilus

The Arab envoys are led to St. Sophia

The envoys of Tarsus appear before the emperor Nicephorus Phocas

Emperor Romanus I sends the Arabs back with gifts

Emperor Romanus III receives an Arab delegation from Beroea (Aleppo, Syria)

The title page of the original text

The final two pages of the original text

The Muslim provinces in the late tenth century