Published by

The E.J.W. Gibb Memorial Trust

The E. J. W. Gibb Memorial Trust and individual authors, 2006.

Paperback edition 2012

ISBN 978-0-90609-457-0

EPUB ISBN: XXXXXXXXXXXXX

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library

Further details of the E. J. W. Gibb Memorial Trust and its publications

are available at the Trusts website

www.gibbtrust.org

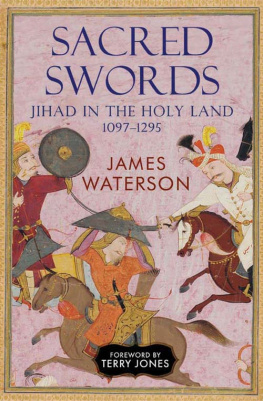

Front cover: Artisans at work on the defences of Iskandar (Alexander) against Gog

and Magog; early Bukhara style ca. 915/1510 to 955/1549 (courtesy of the Bodleian

Library MS Elliott 340, fol. 80a).

Typeset by Oxbow Books, Oxford

Printed in Great Britain by

Short Run Press, Exeter

Contents

(by James Allan)

(Robert Hoyland)

(Robert Hoyland)

(Brian Gilmour)

(Mark Mhlhusler and Robert Hoyland)

(Brian Gilmour and Robert Hoyland)

(Brian Gilmour and Robert Hoyland)

(Brian Gilmour)

List of Figures

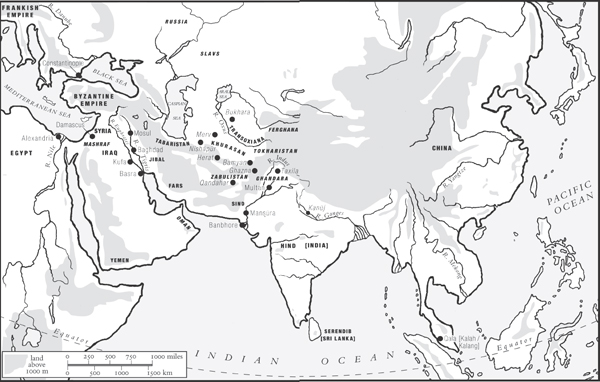

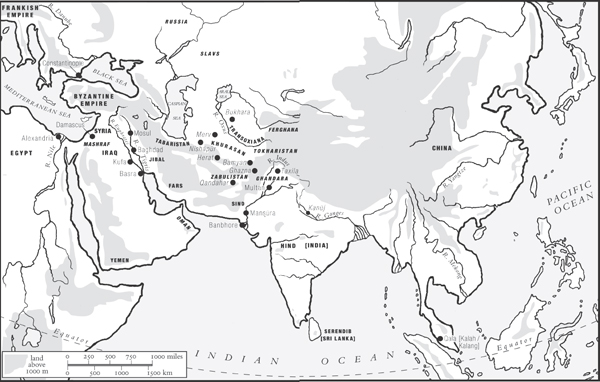

Map of Asia with names of relevant places and regions, between pages 218219

Figure 10 (a) Single-edged Turkish watered steel sword

(b) Detail of the watered surface pattern

Figure 13 (a) Single-edged sword found at Nishapur

(b) Relic steel structure of the Nishapur sword

Figure 18 (a) An early illustration of a furnace for producing crucible steel

(b) Massalskis sketches of steelmaking in Bukhara in 1840

Introduction

James Allan

One of the problems pervading the study of medieval Islamic technology is the lack of surviving technical treatises. Artisans were essentially practitioners of an inherited skill. They worked in industrial quarters, in the narrow confines of the suq or bazaar inside a city, or in more spacious surroundings outside the city walls, where smoke and debris would be less inconvenient for the local population. Rarely able to read or write, they were men of inherited wisdom and experience. Change, if it was required, came through experiment, through trial and error. It was slow and uncertain. Tradition was handed down by example and by word of mouth, and apprenticeships could last for decades. There was therefore no need for texts or manuals.

Fortunately, however, occasional treatises do exist. These are most commonly in the form of lapidaries, like those of Muammad ibn Amad al-Brn (d. 440 AH/1048 AD; see Natural History).

Another written source of information is the manual of the mutasib, the market inspector. This source has never been fully investigated, though some of the manuals have been published, e.g. the Maclim al-Qurba (published by R. Levy in London 1938) of the Egyptian mutasib Ibn al-Ukhuwwa (d. 729/1329). Mutasibs were on the look out for fraudulent activities in the market place; thus Ibn al-Ukhuwwa says of blacksmiths: Blacksmiths must not hammer out knives, scissors, pincers and the like from soft iron, which is of no use for the purpose; some assure the purchaser that it is steel, and this is fraudulent. So though specific information on metal technology is seldom included, it can sometimes be deduced from the warnings given out. A further source is alchemy. Again, accurate conclusions are comparatively rare, even though it was the motivation behind so much scientific research in early Islamic times. Occasionally, however, nuggets of worthwhile information do crop up, as for example in the piece of Jbir ibn ayyn (fl. late second/eighth century) quoted in the first appendix to this book.

Yet other treatises reflect the interests of particular wealthy or powerful patrons. Thus Mur ibn cAl al-arss (fl. 6th/12th century) wrote a treatise on weapons for the Ayyubid ruler of Egypt and Syria, al al-dn (Saladin), which reflects the defensive and offensive interests of his patron. This work includes some valuable recipes for watering on steel. The Aruqid ruler of Diyarbakir (in modern southeast Turkey), Nir al-dn Mamd (596619/120022), was more interested in mechanical toys, especially clocks, hence the treatise on mechanical devices composed for him by Ibn al-Razzz al-Jazr (written in 602/1206). Here again, however, technical information is included so that the clocks could actually be built, and the author also included a fascinating description of how to cast a bronze door. How common were scholar-craftsmen like Jazr is unfortunately unknown, but his existence raises many interesting questions about the craft industries, and indeed about the view of artisans offered at the start of this Introduction.

The treatise of Yacqb ibn Isq al-Kind (henceforth Kindi) on swords was also the result of an interested patron, the Abbasid caliph Muctaim (21827/83342), one of a line of caliphal patrons of scholarship and translation. What might have motivated him to commission this text is an intriguing question. Like any ruler, Muctaim would have had a general interest in his army and its equipment. However, in the aftermath of the fourth Arab civil war he also had a more particular interest in building up a well-trained and well-equipped army. As a result, he imported large numbers of slaves from Central Asia and had them trained as a fighting force. He is in fact generally credited with making slave soldiers into an Islamic institution. This, together with Kindis scientific curiosity, may help to explain why the latters treatise is so specific. It discusses the difference between iron and steel, it distinguishes different qualities of sword blade, and different centres of swordsmithing. It refers to the Indian Ocean trade in steel ingots and to the distinctive character of European swords of the period. It includes technical terms used by the makers, and distinguishes swords by their physical features form, measurements, weight, watered pattern, sculptured details, or inlaid ornaments. If the text reflects the patrons specific interests, then Muctaim was a man with a fascination for technical matters, as well as a concern for military capability. This seems even more to be the case since the discovery of Kindis second treatise on swords: On the making of swords and their quenching (see below), which suggests that Muctaim wanted to know the full details of the recipes used by the smiths for this part of the process.

Other sources of information on swords are diverse and very patchy. Nevertheless, when brought together they can throw important light on the subject, be it from an economic, social, or technical point of view. For this reason, we decided to include a translation of Friedrich Schwarzloses work on Arab swords, which is based on the hundreds of references to them found in early Arabic poetry. This extraordinary compendium of information, written in German, was published some 120 years ago, and it seemed appropriate to recognise its importance by republishing it in English, to bring it to the attention of a much wider, contemporary and future, scholarly audience.

Publication of the texts of early treatises, with or without translations, and republication of works by Orientalists, are not enough in themselves, however. For in both cases interpretation is needed. In two particular areas this is true. Firstly, the Arabic itself needs interpreting, so that the most relevant possible translations of particular words can emerge. Consequently, there was a need for a collaborative effort such as this, and it was our good fortune in having Robert Hoyland available to undertake this part of the project. Secondly, interpretation of a text must focus on, and explain, the technical details. Kindi approached his subject from a scientific point of view, but science was not what it is today. The world has moved on, and if we are to understand what he is saying we have to interpret it in todays language. That need, however, raises its own problems. Technical studies and chemical analyses of early Islamic metals, both ferrous and non-ferrous, exist, but they are patchy and leave so many questions unanswered. The study of technical treatises has therefore to go hand in hand with the scientific research that will lead to greater understanding of the nature of the materials described. Fortunately, Brian Gilmours work over the last few years has pushed deeper into the technology of steel in the Near East, and we can now understand a great deal more about the medieval Islamic tradition than would have been possible even ten years ago. Nevertheless, the present publication will inevitably be but one leap in a continuing game of leapfrog. It will only be a matter of time before future research, both practical and theoretical, throws new light on the history and development of steel, and takes the subject a further leap forward.

Next page