Contents

Guide

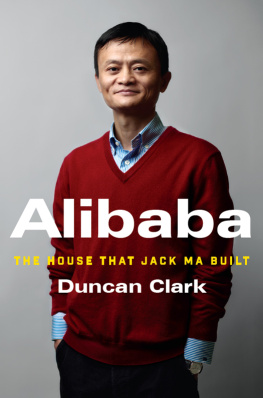

Alibaba is an unusual name for a Chinese company. Its founder, Jack Ma, a former English teacher, is an unlikely corporate titan.

Yet the house that Jack built is home to the largest virtual shopping mall in the world, soon to overtake Walmart in the amount of goods sold. The companys IPO on the New York Stock Exchange in September 2014 raised $25 billion, the largest stock market flotation in history. In the months that followed, Alibabas shares soared, making it one of the top ten most valuable companies in the world, worth almost $300 billion. Alibaba became the most valuable Internet company in the world after Google, its shares worth more than Amazon and eBay combined. Nine days before the IPO, Jack celebrated his fiftieth birthday, the soaring value of his stake making him the richest man in Asia.

But since that peak Alibabas life as a publicly listed company has not gone according to plan. Its shares fell by half from their post-IPO peak, even briefly falling below the initial offer price. Investor concerns were sparked in early 2015 by a surprising entanglement with a government agency over intellectual property, then fueled by the slowing Chinese economy and volatile stock markets, which dragged down Alibabas shares in their wake.

Despite the ups and downs of the stock market, with a dominant share of the e-commerce market, Alibaba is uniquely well positioned to benefit from the rise of Chinas consuming classes. Over 400 million people, more than the population of the United States, make purchases on Alibabas websites each year. The tens of millions of packages generated each day account for almost two-thirds of all parcel deliveries in China.

Alibaba has transformed the way Chinese shop, giving them access to a range and quality of items that previous generations could only dream of. Like Amazon in the West, Alibaba brings the convenience of home delivery to millions of consumers. Yet this comparison understates Alibabas impact. Taobao, its online shopping website, has given many Chinese people their first sense of being truly valued as a customer. Alibaba is playing a pivotal role in Chinas economic restructuring, helping move the country away from a Made in China past to a Bought in China present.

The Old China growth model lasted three decades. Based on manufacturing, construction, and exports, it delivered hundreds of millions out of poverty but left China with a bitter legacy of overcapacity, overbuilding, and pollution. Now a new model is emerging, one centered on catering to the needs of a middle class expected to grow from 300 million to half a billion people within ten years.

Jack, more than any other, is the face of the new China. Already something of a folk hero at home, he stands at the intersection of Chinas newfound cults of consumerism and entrepreneurship.

His fame extends well beyond Chinas borders. A meeting (and a selfie) with Jack is coveted by presidents, prime ministers and princes, CEOs, entrepreneurs, investors, and movie stars. Jack regularly shares the stage with the worlds political and corporate elite. A masterful public speaker, more often than not he outshines them. To go onstage after Jack is a losing proposition. In a remarkable reversal of protocol, President Obama even volunteered to act as moderator for Jack at a Q&A session during the November 2015 APEC meeting in Manila. At the World Economic Forum in Davos in January 2016, Jack dined with Leonardo DiCaprio, Kevin Spacey, and Bono, along with the CEOs of the Coca-Cola Company, DHL, and JPMorgan Chase. The founder of another China Internet company remarked to me: It was almost as though Alibabas PR department was writing Obamas script!

Tom Cruise and Jack Ma in Shanghai, September 6, 2015, at the Chinese premiere of Mission: ImpossibleRogue Nation, which was financed in part by Alibaba Pictures. Alibaba

Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg has been demonstrating his commitment to learning Mandarin Chinese in speeches he has made since 2014, starting at Tsinghua University in Beijing. But Jack, English teacher turned tycoon, has been wowing crowds in both English and Chinese at conferences around the world for over seventeen years.

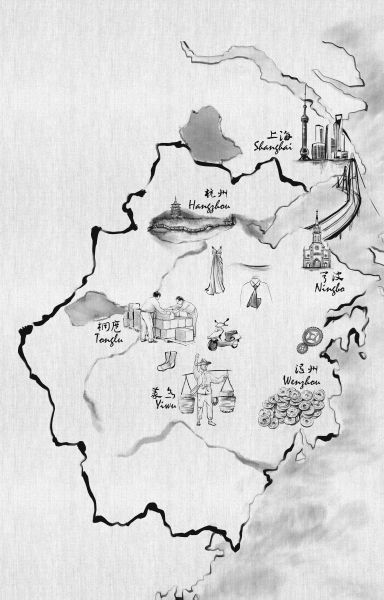

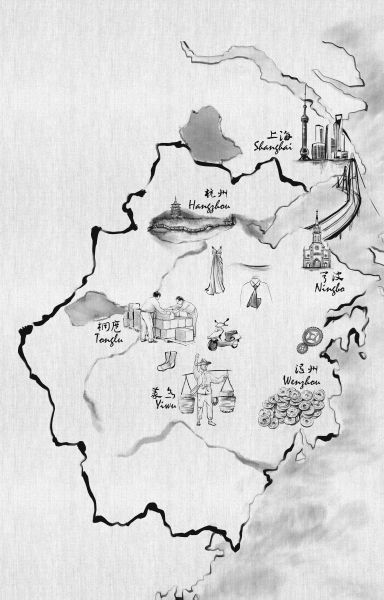

I first met Jack in the summer of 1999, a few months after he founded Alibaba in a small apartment in Hangzhou, some hundred miles southwest of Shanghai. On my first visit, I could count the number of cofounders by the toothbrushes jammed into mugs on a shelf in the bathroom. In addition to Jack, there included his wife, Cathy, and sixteen others. Jack and Cathy had wagered everything they owned on the company, including their home. Jacks ambition then, as it remains today, was breathtaking. He talked of building an Internet company that would last eighty yearsthe typical span of a human life. A few years later, he extended Alibabas life expectancy to a hundred and two years, so that the company would span three centuries from 1999. From the very beginning, he vowed to take on and topple the giants of Silicon Valley. Within the confines of that modest apartment this should have seemed delusional. Yet there was something about his passion for the venture that made it sound entirely credible.

I became an adviser to Alibaba in its early years, helping Jack and his right-hand man, Joe Tsai, with the companys international expansion strategy and recommending to them some of its first foreign employees. Alibaba has assisted me in my research for this book by arranging interviews with senior management and providing access to the company in various locations. But this is an entirely independent account. I have never been an employee of the company and have no professional relationship with them today. My insights come in part from my brief role during the dot-com boom as an adviser to Alibaba and from the proximity that this early contact has afforded since. Yet in writing this book, I have been guided also by my personal experience living in China since 1994, when the Internet first came to the countrys shores, and by my professional career. With support from my previous employer Morgan Stanley, in the summer of 1994, I founded BDA China, a Beijing-based investment advisory firm, which today numbers more than one hundred professionals, consulting to investors and participants in Chinas technology and retail sectors.

As part of the remuneration for my advisory service, in early 2000, Jack and Joe granted me the right to buy a few hundred thousand shares in Alibaba at just thirty cents each. When the deadline was up to buy the shares, in early 2003, things werent looking so good for the company. The dot-com bubble had burst and Alibabas (original) business was struggling. In an error of colossal proportions, I decided not to buy the shares. In the weeks after the companys September 2014 IPO, this mushroomed into a $30 million mistake. I would like to thank you very much for purchasing this book. Writing it has proved (somewhat) cathartic as I explore the stories of others, like Goldman Sachs, who underestimated Jacks tenacity and sold their early stake too soon, and eBay, who dismissed his firm as a rival, only to be forced out of the China market within a few years.

Next page