Copyright 1956 by Eugen Dollmann

First Skyhorse Publishing edition 2017

Foreword 2017 by David Talbot

This book was previously published as Call Me Coward by William Kimber and Co. Limited in London.

All rights to any and all materials in copyright owned by the publisher are strictly reserved by the publisher.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Skyhorse Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or .

Skyhorse and Skyhorse Publishing are registered trademarks of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.skyhorsepublishing.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

Cover design by Rain Saukas

Cover photo by Galerie Bilderwelt/Getty Images

Print ISBN: 978-1-5107-1595-0

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-5107-1597-4

Printed in the United States of America

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

BY DAVID TALBOT

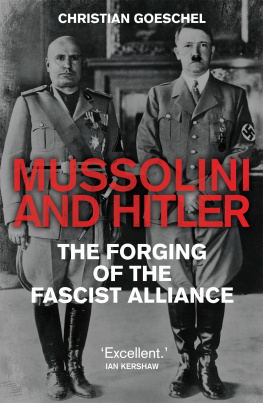

S S COLONEL EUGEN DOLLMANN was not one of the most central figures in Hitlers inner circle, but he certainly was the most dishy. As the Rome-based interpreter who linked together the German-Italian axis during World War II, he had unique access to the Fhrer and his top henchmen, as well as the decadent milieu surrounding Mussolini. He was not as morally depraved as those he served, but his cynicism made him capable of accommodating himself to their baroque evils. Dollmann was a self-serving opportunist who prostituted himself to fascism. That was the succinct historical judgment of Holocaust scholar Michael Salter. And yet, precisely because he did not drink fully from Hitlers poisoned chalice, Dollmann was able to observe his masters from a droll distance like the world-weary characters played by George Sanders. This perspectiveintimate, but detachedmakes his memoirs an utterly fascinating and disturbing reading experience.

Dollmanns companion volumes caused something of a sensation when they were published in Europe under the original titles Call Me a Coward (1956) and The Interpreter (1967). But they have long been forgotten, until now. With Americas descent into its own bizarre nightmare, the discovery of these lost memoirs seems exquisitely well-timed. The inner world of fascist power that Dollmann reveals is both all too human and frighteningly monstrous.

The man who enabled Hitler and Mussolini to communicate with each other was a closeted homosexual, serving a regime that sent thousands of gay men to the gas chambers. This is just one of many ironies that defined Eugen Dollmann. To make things even stranger, Dollmann suggests that Hitlers own fondness for boyish-looking men was a well-known secret in certain German circles during his rise to power.

In one of the most memorable passages of the volumes, Dollmann recalls his frantic shopping sprees in Rome with Eva Braun, Hitlers companion. She loved crocodile in every shape and form, and returned to her hotel looking as if she had come back from a trip up the Congo rather than along the Tiber. Dollmann was fond of the sweet and simple Braun, who confided her sad life to him. She confessed to him there was no sexual intimacy between her and the Fhrer. He is a saint, she told her shopping companion. The idea of physical contact would be for him to defile his mission.

Dollmann also writeswith chilling if bemused styleabout the antics of the debased Italian royalty and the visiting Nazi dignitaries who saw Italy as their playground. His account of a debauched, late-night party at a decaying Neapolitan palazzoenlivened by a troupe of performing dwarves and hosted by a duchessa whose twisted smile was the handiwork of a knife-wielding jealous loveris right out of Fellini. And his chronicle of the evening he spent in a gilded Naples whorehouse with Reinhard Heydrichthe dead-eyed SS general known as the Hangman who was one of the masterminds of the Final Solutionis right out of Viscontis The Damned. Heydrich, who apparently recoiled at the idea of human touch, preferred to take his pleasure from the two dozen half-naked women displayed before him by scattering gold coins across the brothels marble floor and making the women scramble on all fours to gather them.

As the war drew to its close, Dollmann remained a cunning navigator of power, working with a group of wily SS officers to cut a deal with future US intelligence legend Allen Dulles, whose own moral dexterity allowed him to defy FDRs orders and make a separate peace with Nazi forces in Italy. This unholy pact allowed Dollmann and a number of other even more culpable war criminals to escape justice at Nuremberg. But for years after the war, Dollmann was forced to scurry this way and that along the notorious Nazi ratlinesthe escape routes utilized by fleeing German criminals, often with the help of Western intelligence officials.

Dollmann was a master at the Cold War game, offering his spy services to various and often competing agencies. He even tried to extort Dulles, by then CIA director, as his first memoir headed for publication, unsubtly suggesting that anything in the book the spymaster found embarrassing could be made to disappear if the two men reached an understanding.

Dollmann was shrewd enough to realize it was not wise to keep shaking down men like Dulles, and he got out of the spy game. He tried his hand at selling Nazi memorabilia of dubious authenticity. An ardent movie fan, he also put his translation skills at the service of the Italian film industry, providing the German subtitles for Fellinis La Dolce Vita.

You will find no deep moral self-reflection in Dollmanns memoirs. But like many morally compromised men, Dollmann has penetrating insights into the flaws of others.

There was little punishment for his sins. He spent some time confined, fittingly enough, in Cinecitta, the Rome film studio that was briefly turned into a prison after the war, and later at a POW camp on Lake Maggiore that he had the sheer gall (or perhaps sick humor) to compare unfavorably with Dachau, because of the camps watery pea soup and its rain-soaked tents. At least in Dachau they had wood huts, he observed.

Dollmann lived to the age of eighty-four, comfortably cocooned in his later years in a sunny garret in a blue-colored residential hotel in Munich, where he was surrounded by photos, books, and memorabilia that recalled his past life. He was perfectly content to live in the past, he told an American visitor one dayafter all, he had been begun his career as a European Renaissance historian, until he was kidnapped by history.

At one point, his visitor brought up the recently published Dulles war memoir, in which Dollmann was described as a slippery customer. Dollmann, whose grasp of English was unsure, asked his guest to explain the meaning of the term and was told that it was someone who was shrewd, cunning, Machiavellian.

The old SS mans face lit up with a smile. Oh! That is a complimentfor me.

INTRODUCTION

BY FIELD-MARSHAL KESSELRING

E UGEN DOLLMANN is a brilliant personality of high intelligence and great personal charm, a man of great diplomatic abilities and a witty conversationalist who was persona grata in Roman society. He was also an S.S. officer.

His personal qualities are well reflected in this book, and he has a humorous and ironical pen which is no respecter of persons, andas its title indicatescertainly not of his own.

Next page