For Anita and Keith

First published in 2007 as Queen Elizabeths Wooden Teeth

This revised and updated edition published in Great Britain in 2014 by

Michael OMara Books Limited

9 Lion Yard

Tremadoc Road

London SW4 7NQ

Copyright Andrea Barham 2007, 2014

All rights reserved. You may not copy, store, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN: 978-1-78243-036-0 in hardback print format

ISBN: 978-1-78243-095-7 in e-book format

Designed and typeset by K DESIGN, Winscombe, Somerset

Picture Acknowledgements:

Getty Images: see

www.mombooks.com

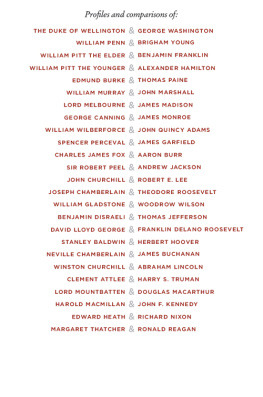

CONTENTS

It is said, in a history book I was recently browsing through, that Boadicea rode a scythed chariot. (She didnt.) It is said (in the same publication) that in the Roman Colosseum, Christians were thrown to lions. (They werent.) On BBC Televisions Junior Mastermind, small children were informed that Sir Walter Raleigh is said to have brought back the potato and tobacco from the New World. (Raleigh never went to North America.)

Such fictions are so entrenched in our collective consciousness that it is said assertions have become part of our history, despite the fact that they never happened. In this book, I strive to reveal the truth behind ninety historical misconceptions and fallacies, in the hope that it is said history will be for ever consigned to the rubbish bin. Why repeat inaccuracies? Thats what we have politicians for.

ANDREA BARHAM

Vikings wore horned helmets

No modern-day, Viking fancy-dress costume would be complete without a horned helmet. Indeed, Norse Valkyrie and Wagners Ring Cycle heroine Brnnhilde is invariably portrayed sporting one. Even the cartoon Viking Hgar the Horrible is depicted complete with horned headgear. However, the popular helmet featuring two prominent horns is a glaring anachronism.

In The Viking World, James Graham-Campbell clearly states that Viking helmets did not have horns. Author of Vikings and their Origins Chris Webster explains that although illustrations of Vikings show horned or winged helmets, no examples of such helmets have been found, adding that poorer warriors would have worn a simple conical helmet, or a leather cap. In The Vikings, it is revealed that this common error results partly from mistaken dating by early antiquaries of finds from other northern European cultures and from crude depictions of warrior figures... dedicated to Odin. According to Webster, the raven (Odins bird) was often depicted on top of the helmet with the wings forming a circle to the left and right sides. He suggests that these wings can easily be mistaken for horns, especially as the ravens head often cannot be distinguished in profile.

Pre-Viking Norse horned helmets did exist, however, as A. F. Hardings work European Societies in the Bronze Age features a picture of two beautiful bronze examples from Viks, Zealand, housed in the National Museum in Copenhagen. The narrow, curved horns are twice the length of the helmet. Such helmets were probably reserved for ceremonial purposes. The two in question certainly look like they would be very tricky to wear on a daily basis. Given that the Bronze Age finished in 1000 BCE and the Viking era began in the ninth century CE , the Vikings would no doubt have regarded the horned helmet as being nearly 2,000 years out of date: hardly the height of fashion.

Next time you are called upon to dress up as a Viking, remember that there is no obligation to don any horned headgear. This way, youre much less likely to have problems using public transport.

All gladiators were male

The female version of gladiator is gladiatrix. The word exists because female gladiators existed; they were generally thrill-seekers from the upper classes. In Gladiators: 100 BC AD 200, Stephen Wisdom reveals that Roman writer Petronius Arbiter mentions a woman of the senatorial class [ruling class] fighting as a female gladiator. Gladiatrixes were the exception rather than the rule. In his work Life of Domitian, late-first-century Roman biographer Suetonius describes how Emperor Domitian staged... gladiatorial shows by torchlight, in which women as well as men took part. Roman satirist Juvenal was appalled by the concept of female gladiators. In Satire VI: The Ways of Women he asks, what modesty... can you expect in a woman who wears a helmet, abjures her own sex, and delights in feats of strength? Writing a century later in Roman History, Roman historian Cassius Dio tells of an expensive festival staged by Emperor Nero where women fought as gladiators, some willingly and some sore against their will. Dio, concerned less with the barbarity, commented that all who had any sense lamented... the huge outlays of money. Emperor Tituss festival failed to find favour with him either: animals, both tame and wild, were slain to the number of nine thousand; and women (not those of any prominence, however) took part in dispatching them.

Wisdom reveals that the British Museum houses a marble relief of two female gladiators. One of these is referred to in the inscription by her stage name, Amazonia. He comments that despite people being routinely hacked to bits in the arena, public sensibilities were protected from the sight of bare-chested women fighters. He further explains that some sources described how such women covered their breasts with a wrap-around bandage and later a strophium, which was a band of fabric that served as a Roman sports bra.

Women were repeatedly discouraged from taking up gladiatorial fighting. An entry in Gladiator: Film and History reveals that a 19 CE edict known as the Tabula Larinas stated that it should be permitted to no free-born woman younger than the age of twenty... to offer... herself as a gladiator. This was not because of the inherent danger of the sport, but because fighting in the arena was not considered a respectable trade for a well-born Roman.

Emperor Septimius Severus ended the practice in the third century when, as Alison Futrell explains in The Roman Games, he discovered that spectators were making disrespectful comments about high-born women. Watching the butchering of animals and criminals in their hundreds was one thing, but speculating on the amorous capabilities of a well-born woman was quite another!