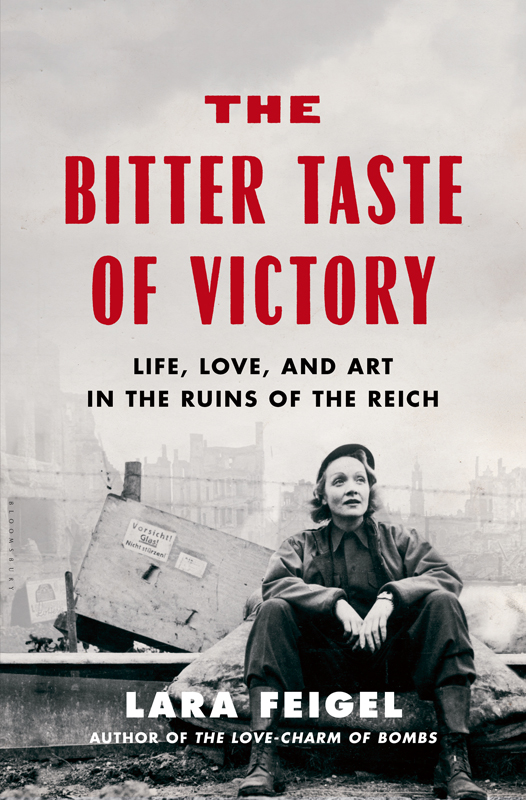

THE BITTER TASTE OF VICTORY

THE BITTER TASTE

OF VICTORY

Life, Love, and Art in the Ruins of the Reich

Lara Feigel

For John

Contents

Crossing the Siegfried line: NovemberDecember 1944

Advance into Germany: JanuaryApril 1945

Victory: AprilMay 1945

Occupation: MayAugust 1945

Berlin: JulyOctober 1945

German Winter: SeptemberDecember 1945

Nuremberg: November 1945March 1946

Fighting the Peace: MarchMay 1946

Boredom: MayAugust 1946

Judgement: SeptemberOctober 1946

Cold War: October 1946October 1947

Artistic enlightenment: November 1947January 1948

Germany in California: JanuaryJune 1948

The Berlin Airlift: June 1948May 1949

Division: MayOctober 1949

When I tell people that I am writing a book about postwar Germany, they often ask if Feigel is a German name. In fact as far as I know its origins are Polish; when my fathers stepfather moved to Belgium in the 1920s he must have altered the spelling to fit in. Or perhaps it was just before the war that he changed his name from sounding Jewish to sounding German. At that stage he was married to my grandmothers sister, and I now realise that I dont know my actual grandfathers name. What I do know is that the Germans were not popular either with my fathers Jewish family, who spent the war in concentration camps, or with my mothers Dutch family, who spent the war eating tulip bulbs in occupied Amsterdam. My Dutch grandmother still freezes every time she hears German spoken and is alarmed when I go to Germany.

And yet I have been drawn repeatedly to Berlin, a city I love, whose stacked up layers of history I find endlessly compelling. My German is better than either my (nonexistent) Dutch or Yiddish. Am I erasing family history as I cycle happily down Unter den Linden or past the Reichstag, carelessly oblivious of the buildings where Hitler plotted the events that destroyed the lives of my grandparents? Or am I confronting something that neither side of my family is able to confront, forcing us into the pan-European future that so many people (but not, I think, my grandparents) hoped to bring about in 1945? If I am then it took me some time to reach this point, and it now seems inevitable that I should have arrived in Germany in the safe company of 1940s British writers.

My interest in the Second World War began in London and not in Europe. This was a war where the tragedy played out on a manageable scale: a war where people had parties and love affairs amid the bombing and, most crucially, a war that could be talked about and written about. Often it is only in retrospect that we see why we write the books we do. In India a year after it was published, I was asked by a journalist how Id come to write The Love-charm of Bombs, my chronicle of the lives of five writers in wartime London. Had my own family been based in London? I answered that in fact I thought this exuberant celebration of Englishness (albeit in the company of one exiled Austrian writer, Hilde Spiel) was a retreat from my family, where the war was unmentionable, both for the Dutch and the Jews. You do not ask any of my grandparents casually what they were doing in the war, and as a result I know of their experiences only in pieced-together fragments, too shocking to be referred to again.

It is both strange and inevitable that this revelation should occur so far from home. Now it seems obvious that The Love-charm of Bombs came out of a lifelong desire to make myself as English as possible, chiefly through immersing myself in English literature past and present. For all those years of studying English literature, of reading delightedly about redoubtable English eccentrics from a lost age, I was creating an alternative ancestry for myself. And then in identifying myself with Elizabeth Bowen as she paced along the blacked-out streets, in imagining myself sheltering from the bombs with Graham Greene, I was claiming the war in London as my own heritage.

But it turned out to be more complicated. Not all British writers stayed put in London; some went to Germany and Austria. They visited the remains of the concentration camps where my fathers family had been imprisoned; they saw Hitlers emaciated victims. While editing Stephen Spenders journals, I travelled to Germany with him in 1945, reading his astonishing account of the German ruins. While writing The Love-charm of Bombs, I followed Graham Greene and Elizabeth Bowen to Austria and Peter de Mendelssohn to Germany. It turned out that dozens of British and American literary and artistic figures had been sent to Germany in 1945 to witness the destruction, or begin to help reconstruct the country their governments had destroyed. Alongside Spender, there were other British figures I had written about previously: W. H. Auden, Humphrey Jennings, Rebecca West. Perhaps even more interesting were the Americans: Martha Gellhorn, Ernest Hemingway, Lee Miller. And then there were the Germans and Austrians, sent to Germany in the uniform of the conquerors: Klaus and Erika Mann, Carl Zuckmayer, Billy Wilder.

Fascinated by these unexpected stories of Anglo-German collisions, I found that I could not stay away from the war in Europe forever. I found that the world of literary London and the world of my family were not as easily separable as I had made them. I had already come to love Berlin, where I had discovered a life of cycling, swimming and cafs that was conducive to writing. Now I became more concerned with peeling back its layers of history and seeing what remained of the Nazi era, curiously overlaid with the legacy of the Occupation that had ended up dividing the city in two.

Ive now spent more time in Germany than anyone else on either side of my family. I also know more about the war in Europe than I initially wanted to know. Whether 1945 was a moment of hope or a moment of despair is explored in the pages that follow. What is certain is that it was a time that put any neat cataloguing of nationality in doubt. Indeed, for people like Stephen Spender this disruption of straightforward boundaries between nations was a positive effect of a war that had the potential to reconfigure Europe as a transnational entity united by its common culture. Perhaps one day another journalist will ask me if the book reflects my own wartime heritage and no doubt I will be surprised by my answer. Perhaps that will be the moment when I make sense of my English accent and preoccupations, my eastern European and Dutch ancestry and my German name.

To arrive in Germany in the final months of the Second World War was to confront an apocalypse. Berlin, Munich, Cologne, Frankfurt, Hamburg, Dresden the old names had nothing to do with the rubble that now spread for mile after mile, scattered with corpses. In Berlin, the streets were not flattened altogether. Instead, only the faades remained; thin strips of mortar and plaster whose blown-out windows exposed emptiness where homes had crumbled behind them.

Almost all the cities in Germany had been badly bombed. By the end of the war a fifth of the countrys buildings were in ruins.