For Sophie Elena Gray and Tobias Rutledge Gray

The staff of the Research Library of Sir John Soane Museum made several summer days spent in the librarys collections enormously helpful. I am grateful to the librarian, Dr. Stephanie Coane; Stephen Astley, drawings curator; the head of library services, Susan Palmer; and Bellina Adjei, who expertly handled permissions. At the Pennsylvania State Archives, I benefitted greatly from the expertise of Associate Archivist Michael D. Sherbon, who helped me locate images of the Camelback and Dunlaps Creek bridges.

I was able to review the papers of the late J. G. James, the worlds foremost student of early iron bridges, at the Institution of Civil Engineers in London. I am grateful to the institutes librarian, Debbie Francis, for providing me access to these and other invaluable materials.

Ms. Polly Munson of Peyton, Colorado, contacted me some years ago about a brief piece I wrote on Paine for the online journal Common-Place. She is a descendant of John Hall and came into possession of his letter books, which she has carefully transcribed and which, to my great benefit, she very generously shared with me.

James N. Green, librarian of the Library Company of Philadelphia, very kindly granted me access to the John Hall Diaries and fielded numerous obscure queries with his customary good humor. Rob Karnowski, a graduate student Florida State University, did yeomans work, transcribing sections of the Hall Diaries. David Brackett, another descendant of John Hall, shared with me his encyclopedic knowledge of his ancestors biography. Andrew McCarthy, a brilliant undergraduate at Florida State University, spent a summer expertly checking citations and sharing with me his extensive knowledge of eighteenth-century architecture.

My agent, Lisa Adams of the Garamond Agency, has been an utterly indispensable source of encouragement and wise counsel. At W. W. Norton, I have had the great privilege of working with Steve Forman, a master of the editors craft. Steves editorial assistant, Travis Carr, has helped in innumerable ways. I am also grateful for Trent Duffys exceptionally careful copyediting.

Two friendsJane Kamensky and Ray Raphaelread an early draft and helped me find my way to the story I was trying to tell.

For everything else, thanks especially to Stacey Rutledge.

The mechanic should sit down among levers, screws, wedges, wheels, & c. like a poet among the letters of the alphabet, considering them as the exhibition of his thoughts; in which a new arrangement transmits a new idea to the world.

ROBERT FULTON,

A Treatise on the Improvement

of Canal Navigation (1796)

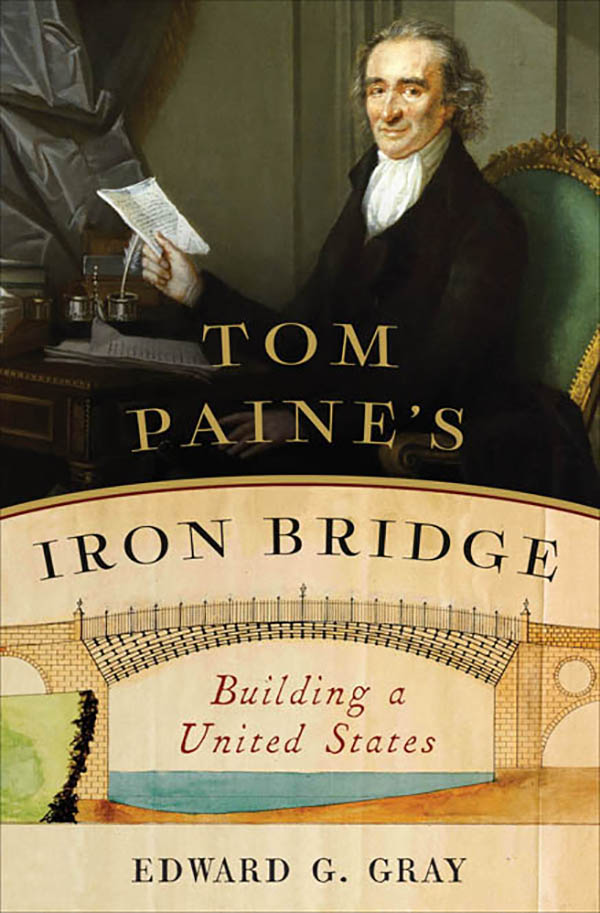

ALSO BY EDWARD G. GRAY

The Making of John Ledyard: Empire and Ambition in the Life of an Early American Traveler

New World Babel: Languages and Nations in Early America

AS EDITOR

The Oxford Handbook of the American Revolution (with Jane Kamensky)

Colonial America: A History in Documents

The Language Encounter in the Americas, 14921800 (with Norman Fiering)

I N THE EARLY FALL of 1774, as the London Packet sailed through the mouth of Delaware Bay and up the river toward Philadelphia, its 120 passengers lay about the vessel, weak and thin. Their passage to America had been brutal. Shortly after leaving England, a putrid fever swept through the ship. The illness ravaged passengers and crew alike, killing five and leaving the ships English captain, John Cooke, fighting for his life. Fortunately a doctor was aboard; he was able to administer the array of unctions, reassurances, and spirits that were the staples of eighteenth-century medicine.

Among the physicians patients was the thirty-seven-year-old Thomas Paine. Paines case was particularly severe. After the London Packet docked at the Philadelphia wharf, he continued to waft in and out of a feverish delirium, unable even to raise himself long enough to traverse the gangway from ship to shore. A Philadelphia doctor took charge of Paines care and made arrangements for him to be taken to the home of relatives of Captain Cooke. There, Paine would spend the next

Paine was not typical of the passengers aboard the London Packet. Most were indentured servants, many traveling with families, bound by legal agreements to repay the cost of transit with as many as six or seven years labor. The vast bulk of that labor would take place on the small farms that dotted the Delaware River valley, or the rapidly expanding counties to the south and west, across Philadelphias other river, the Schuylkill.

Paine came as a free man. He was beholden to no one, with the possible exception of his physicians and the great Benjamin Franklin, whom he had met in London and whose letters of introduction would ease Paines arrival in America. He was also a man of means, or at least of sufficient means to avoid the kind of indebtedness that most likely landed many of his fellow passengers in servitude.

PAINE WAS BORN in 1737 into Englands growing middling population. His father, a Quaker stay-maker, and his mother, the Anglican daughter of an attorney and town clerk, were able to provide a basic education for their only child (Paines younger sister, Elizabeth, died as an infant). But by age twelve, Paine was forced to start working, first as an apprentice to his father and subsequently as a common seaman aboard the British privateer King of Prussia. Life at sea did not agree with the young Paine and he returned to stay making, establishing a shop in Sandwich, Kent. The twenty-two-year-old Paine also married Mary Lambert, but a year after their marriage, Mary died in childbirth and Paines business began to fail.

Looking beyond the family trade, Paine seized on a new career path. After Marys death, he returned to his parents home in Thetford, Norfolk, to prepare for entry into the Excise Service, the government agency charged with collecting taxes on beer, spirits, wine, leather, paper, soap, candles, and other taxable goods. Following the path of his father-in-law, James Lambert, Paine would spend over a year seeking to become one of Britains more than 2700 excise officers.

Preparations for the Excise was, in some ways, not unlike those for other eighteenth-century professions, whether the military officer corps, the clergy, the law, or medicine. It involved a combination of specialized study, exams, and patronage. If successful, it promised the possibility of ascent from the lowly gaugers, who counted, weighed, and measured taxable goods, to regional supervisors, excise collectors, and then to the examiners, accountants, and commissioners who oversaw the whole elaborate excise system from the Excises London offices.

Paines preparations paid off, and he was awarded a post as a gauger of brewers casks in the Lincolnshire town of Grantham. Because there was little uniformity in the size of containers brewers used to transport their beer, the gauger had to employ complex mathematics to calculate each containers contents. Paine mastered these techniques and was soon promoted to a better paying position at Alford, a Lincolnshire town closer to the North Sea coast. But Paines new career turned out to be little better than his earlier one. In 1765 he was discharged from the Excise for stamping (this term applied to a range of infractions, usually involving falsified records). Although the offense was a serious one, it was common and rarely clear-cut. Given their poor pay, long hours, and often difficult working conditions, and given that gaugers came to know their clients practices, the temptation to introduce shortcuts was hard to resist. There was little reason to measure the casks of a brewer whose output rarely changed.

Next page