I dedicate this account of my experiences before, during and after the Holocaust to my children Raphael and Maya and my grandchildren Ben, Simon, Joanna and Abraham-Peter

A memorial to my mother and father and the millions who were silenced and whose stories will never be told; and a tribute to my sister Renate and my faithful companions of the camp orchestra who shared these traumatic years with me

And so the survivor told himself that not to remember was equivalent to becoming the enemys accomplice: whosoever contributes to oblivion finishes the killers work. Hence the vital necessity to bear witness lest one find oneself in the enemys camp.

Preface

There are many features of this memoir which give pause for thought. From the old tattered bundle of letters which Anita Lasker-Wallfisch reopened towards what she calls the end of my labours, a veritable treasure trove emerged. In it can be seen, on the eve of war, the painful process of failing to obtain the necessary documents, guarantees, etc, to leave Germany. There is a cruel sense of time running out, and of British Jewish bureaucracy fumbling, with lack of funds a constant nagging feature.

Contemporary letters have a tremendous power to recapture the atmosphere of that time, including, even in dark days, the survival of humour. There is also, once war comes in September 1939, the continued survival of hope. Perhaps the enforced move from home will be temporary. Perhaps emigration will still be possible. As late as April 1940 there are hopes that departure from Germany might still be an option, possibly to Italy. On every page the reader, knowing the actual outcome of German Jewrys fate, is gripped by the spell of hindsight.

When Anitas sister Marianne despatches two pounds of coffee from her new home in Britain, it offers all the delights of the miracle drink and the hope of more coffee to come. Hope, like coffee, helped sustain morale. Anita writes: Hope was an elixir that kept us going. But like the coffee, and the travel plans, it was in short supply. In January 1941 a letter from Anitas mother reached her daughter in London. Well, perhaps in spite of everything, the mother writes, we will all five of us sit down at a cosy round table one day!

The denouement was long drawn out and cruel. The terrible fate of Germanys Jews was in such violent contrast to their culture and qualities. This book is a testimony to the maintenance of those qualities to the very end. In July 1941 Anita was sixteen years old. There were still elements of normality in Breslau nearly two years after the outbreak of war: her birthday presents included a history of art and an historical atlas, soap and a pair of socks. In the afternoon we played quartets.

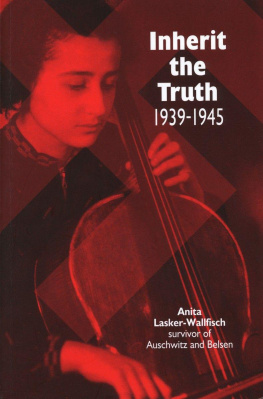

In April 1942 Anitas parents were deported. Her grandmother was deported soon afterwards. The destination was unknown; they were never heard of again. With those deportations, all hopes were destroyed. Anitas own path (beginning with a failed attempt, together with her sister Renate, to escape by train to German-occupied Paris) went through Auschwitz to Belsen. In Auschwitz she was in the camp orchestra: to this, she owed her life. I may no longer have had a name, but I was identifiable. I could be referred to. I was the cellist. I had not melted away into the grey mass of nameless, indistinguishable people.

The moment of liberation for Anita and her sister was at Belsen. When the first tank finally rolled into the camp, Anita writes, we looked at our liberators in silence. We were deeply suspicious. We simply could not believe that we had not been blown up before the Allies could get to us. Like so much in this book, the story of liberation brings a chill to the spine and the realization of the miracle of survival. Anita Lasker-Wallfisch has given an account which, in its personal immediacy, conveys many elements of the almost unconveyable.

Martin Gilbert

Merton College

Oxford

1st March 1996

Acknowledgements

My thanks to Louise Greenberg who asked me for some first-hand information about Theresienstadt for a programme she was preparing for the BBC. I said I could not give her any because I was not there; but if she should want to know about places like Auschwitz and Belsen, I could possibly help. This resulted in the BBC broadcasts about my experiences entitled Inherit the Truth, adapted from my original text by Colin McLaren, and an avalanche of letters with inquiries as to where the book could be obtained. They were followed by an unexpected offer to publish what I had originally intended to be for immediate family use only.

I owe special thanks to my publisher and editor Giles de la Mare who with admirable patience made me see that there is a big divide between the spoken and the written word and also that the English language has a lot more grammar than I had given it credit for.

I would also like to thank the Public Record Office who generously permitted me to use the transcript of the Lneburg trial (ref. WO 235/14, Crown Copyright, reproduced with the permission of the Controller of Her Majestys Stationery Office); Random House for permission to include the quotation from Elie Wiesels A Jew Today ; and everyone who encouraged me to go ahead with this venture.

Illustrations

HALF-TONE ILLUSTRATIONS

ILLUSTRATIONS IN TEXT