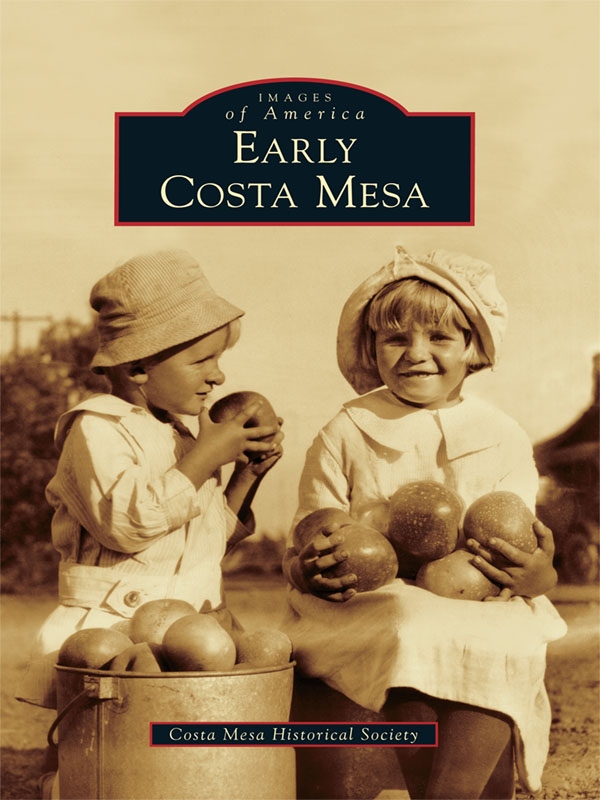

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Preparing Early Costa Mesa for publication has been a journey of rediscoveryparticularly for those of us who have worked with the collections of the Costa Mesa Historical Society for many years. We have revisited the events that defined and shaped the early development of Costa Mesa and have scoured the depths of our collections in search of images and documents that would tell the story clearly and succinctly.

Thus the first of our acknowledgments is to all those who have donated materials from their personal and organizational collections to the historical society for preservation and promotion of local history. Without these donations from hundreds of community members and their families, this book would not have been possible.

We have relied heavily on the Edrick Miller collection and upon Eds seminal book, A Slice of Orange . Our community owes a profound debt of gratitude to Ed for researching, collecting, and copying many original photographs and documents and for recording interviews with early settlers. The Costa Mesa Historical Society is privileged to be the repository for Eds research materials, photographic reproductions, and recordings.

The City of Costa Mesa is acknowledged for its partnership with the historical society since the societys founding in 1966. Our relationship facilitates the preservation and promotion of local history through museum exhibits, cataloged resources, public outreach, and school educational materials. The Costa Mesa Historical Society is pleased to be part of the citys program for enhancing our residents sense of community.

Several people researched and/or contributed family history items: Keith Hall, Jerry Platt, Richard and Shirlee Opp, Chisholm Brown, Dave Gardner, Dick Stanley, Louise Rusher, and Joyce Brown. Peggy Gardner and Keith Hall created illustrations that we gratefully acknowledge. Unless otherwise noted, all images appear courtesy of the Costa Mesa Historical Society.

Also we wish to thank Prof. Hank Panian for his review and constructive criticism of the manuscript and our editors at Arcadia Publishing for their patience and guidance throughout the creation of this book. We wish to note in particular that editor Jerry Roberts stayed on the telephone answering our questions even while a magnitude 5.4 earthquake shook him for nearly a minute!

Art and Mary Ellen Goddard

Costa Mesa Historical Society

Find more books like this at

www.imagesofamerica.com

Search for your hometown history, your old

stomping grounds, and even your favorite sports team.

One

EARLY PERIODS ON THE MESA

Evidence uncovered in several local archaeological digs shows that Costa Mesa was home to at least two different Native American cultures. These peoples were hunter-gatherers who used stone tools and implements such as the grindstones and arrowheads shown above. Cogged stones, shown at center above, are unique to the region and may have been used during religious or burial ceremonies. Lacking both pottery and metals, native inhabitants often tarred their baskets to hold liquids.

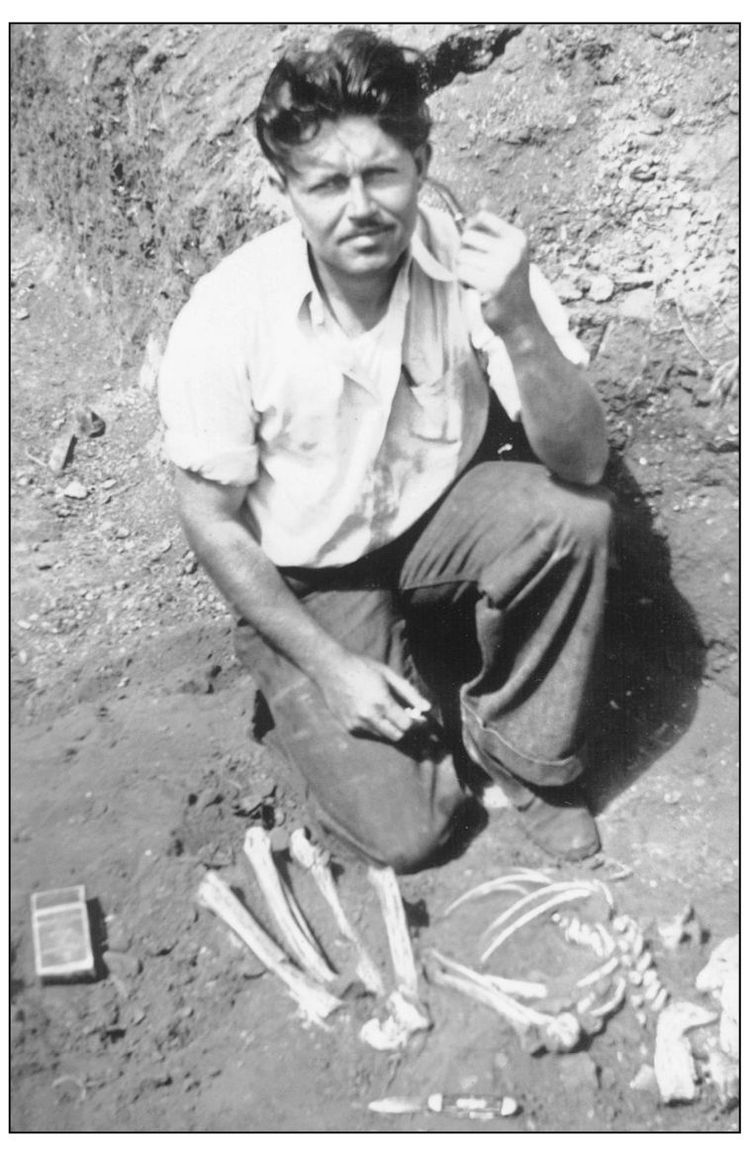

Archaeologist John W. Winterbourne kept detailed notes of the Adams-Fairview excavation during April and May 1935. Along with the Native American skeleton pictured at left, the dig uncovered beads, dishes, tools, ceremonial stones, skulls, and skeletons in an area generally north of the Diego Sepulveda Adobe. The Depression-era excavation was a project of the Works Progress Administration (WPA). (Courtesy of the Pacific Coast Archaeological Society.)

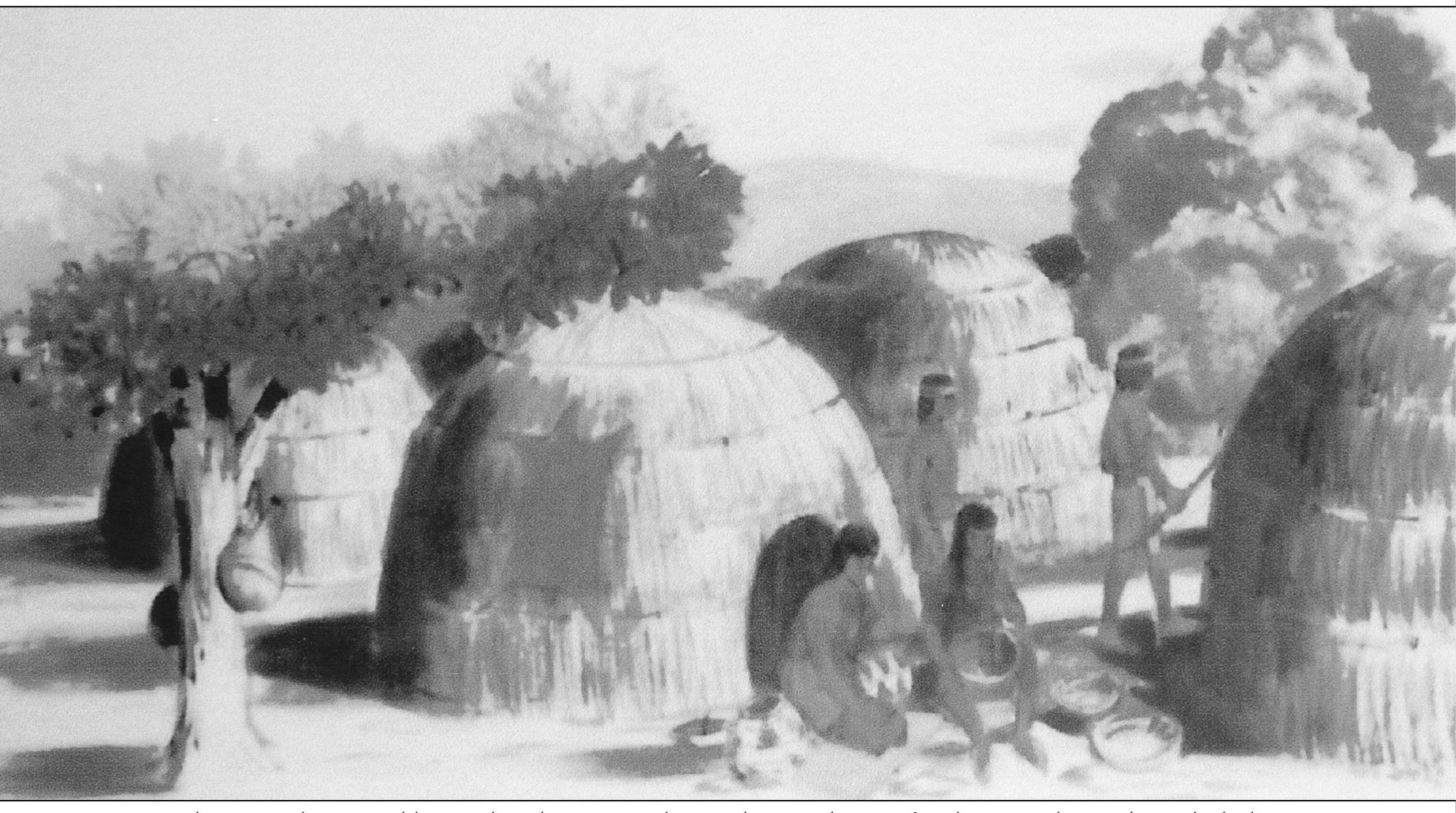

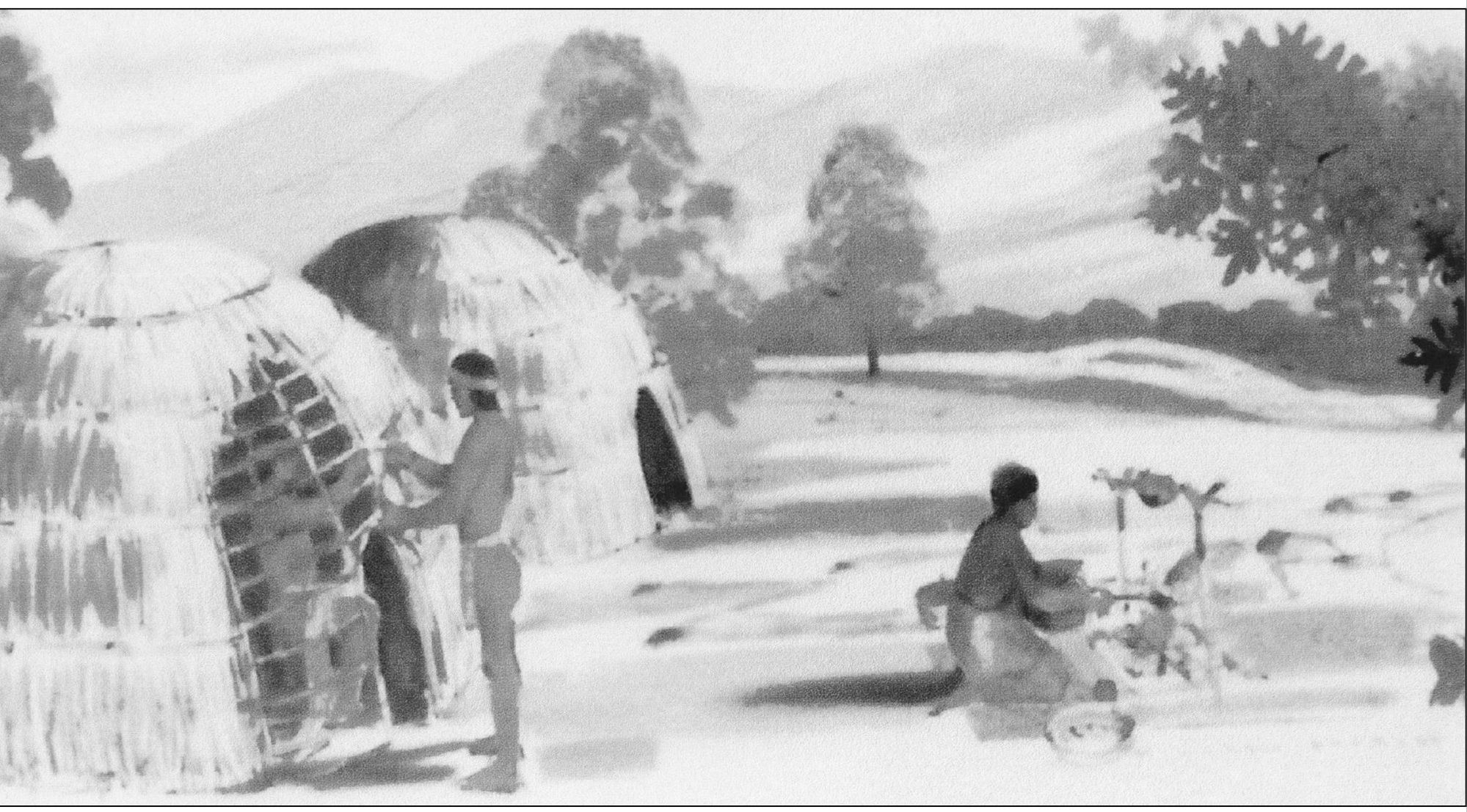

In this mural painted by Richard Garcia Chase, the residents of Lukup go about their daily lives within sight of a double-domed mountain they named Kalawpa (today Old Saddleback). Their wikiups were practical dwellings that, should they become infested with vermin, were burned

down then rebuilt nearby. Chase painted this and two other murals displayed in the Crocker Bank located at the intersection of Newport and Harbor Boulevards.

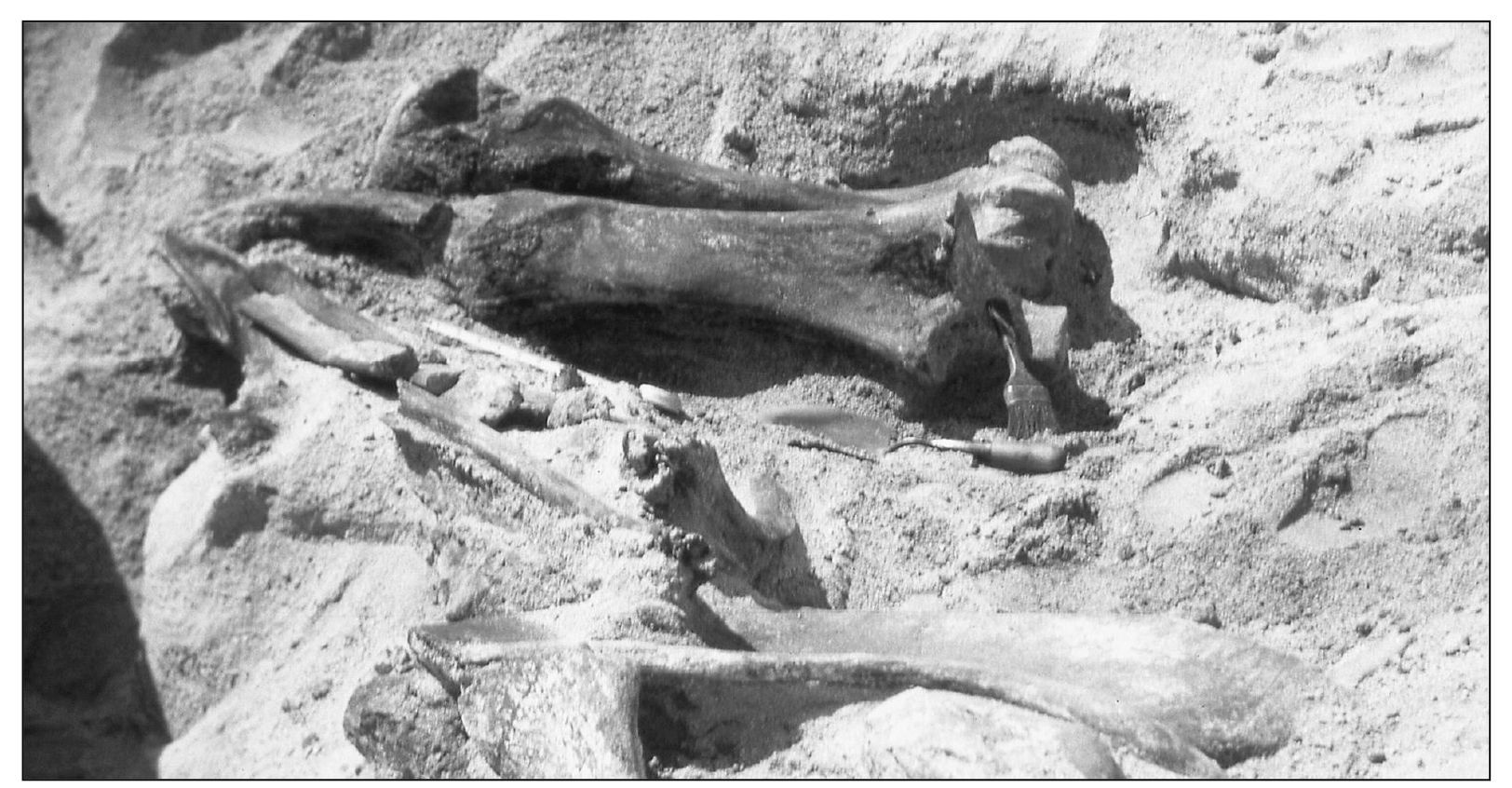

Mastodon bones were found near the intersection of Boa Vista Drive and Nevis Circle in the summer of 1962, as the area was being graded for a housing development. The bones were taken to the Bowers Museum in Santa Ana for further study and then placed on display at local schools. Speculation continues about how the bones arrived in Costa Mesa; did mastodons roam this area or did the remains wash down the Santa Ana River in a past flood?

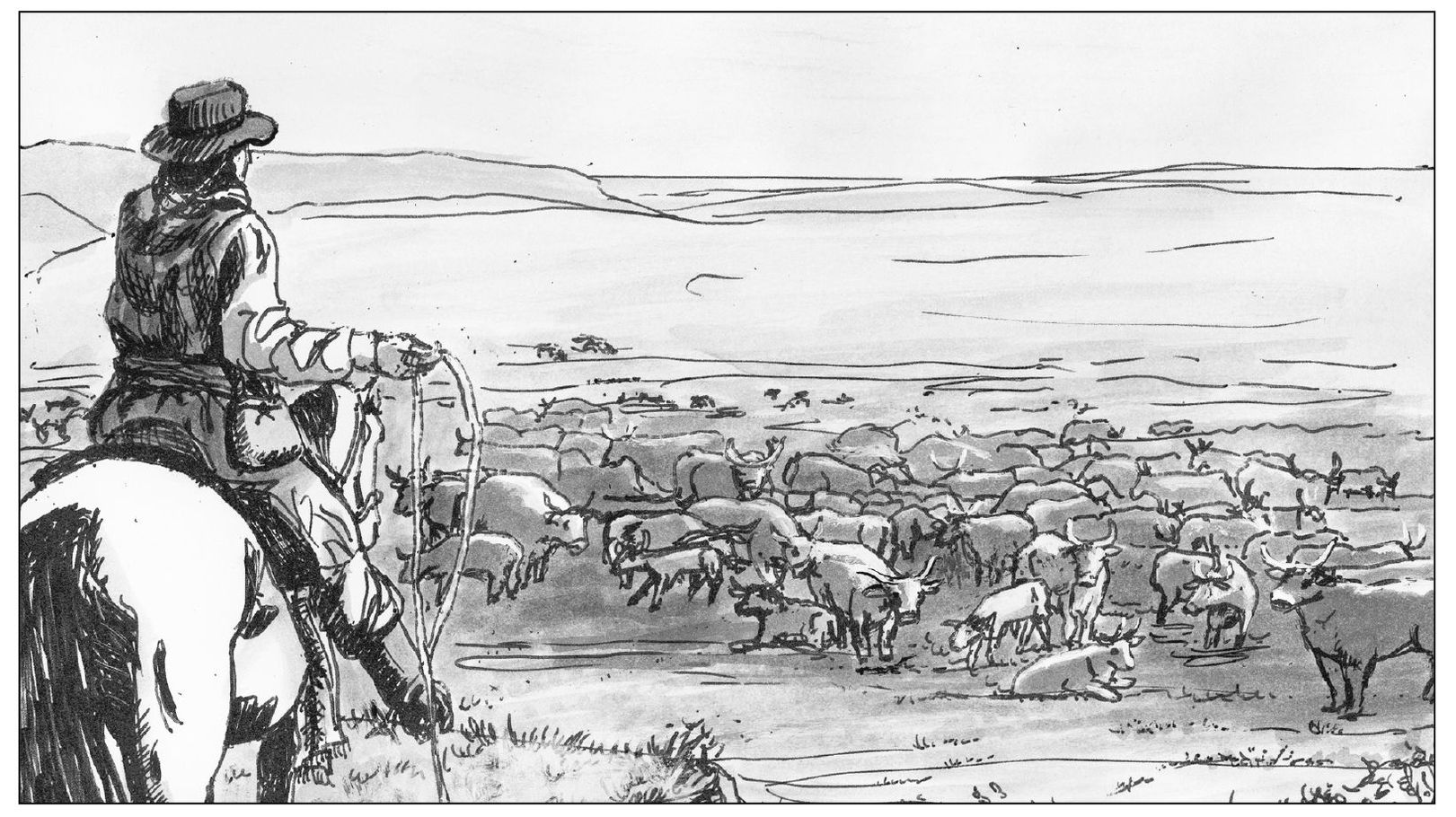

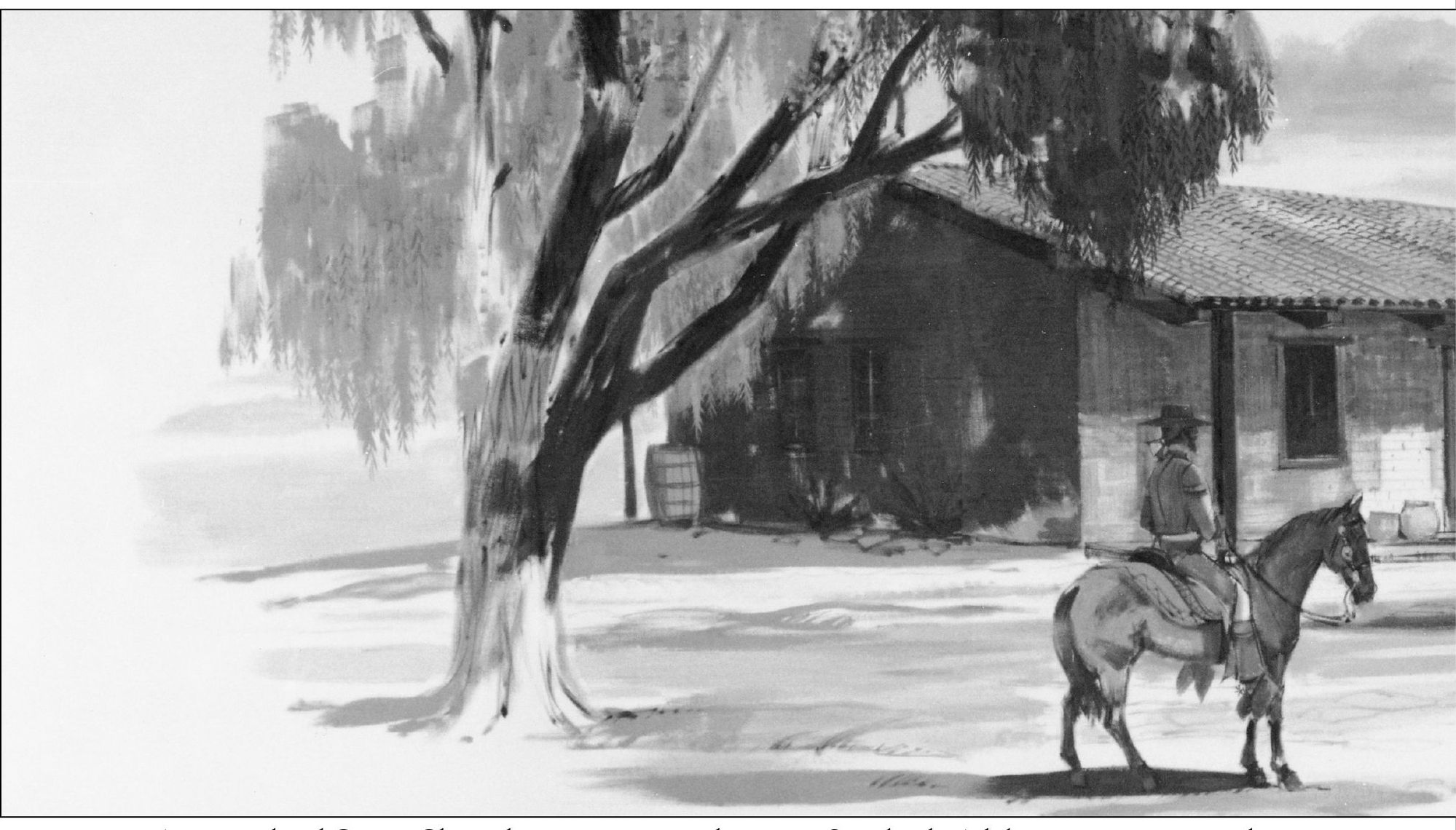

Vaqueros took advantage of the bluffs overlooking the Santa Ana River lowlands to keep a watchful eye on their herds. Shown above is the view looking south from a point near the Polloreno Adobe (see map on page 2). (Illustration by Peggy Gardner.)

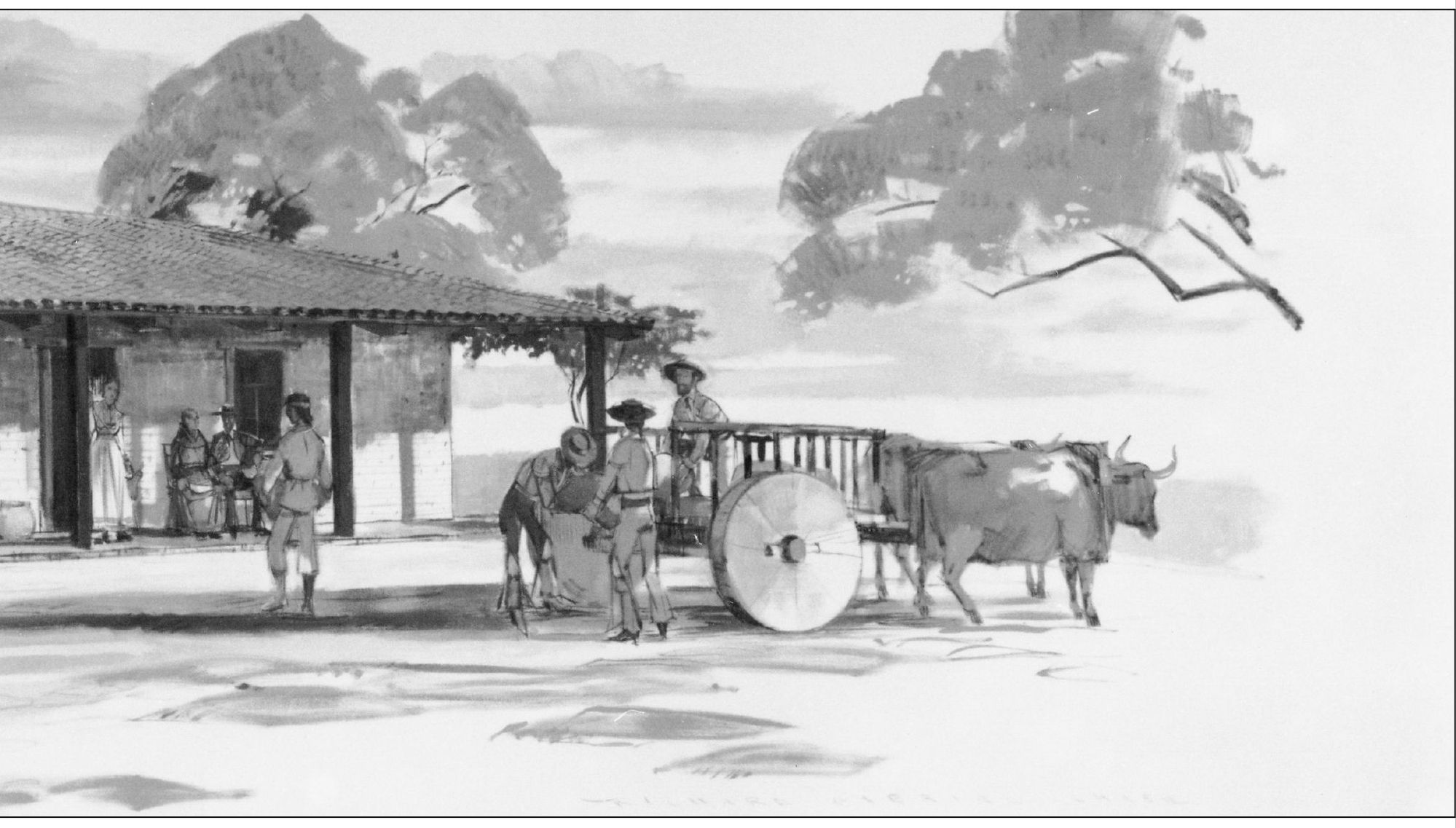

Artist Richard Garcia Chase depicts a scene at the Diego Sepulveda Adobe centering on ranching activities between 1820 and 1840. The majordomo and a friar confer on the front porch while ranch hands go about their tasks. The adobe structure was built using large mission bricks fabricated

of brown adobe mud with a binder of wild wheat straw. The 2-foot-thick walls and daily onshore breezes kept the buildings interior cool during the summer. Chases mural was displayed at the Crocker Bank at the intersection of Newport and Harbor Boulevards.

In the years before 1868, when he pastured cattle on the property, Don Jos Diego Sepulveda made improvements to the adobe that bears his name. Based on Yorba family relationships, he assumed he had clear title to the house and surrounding land. But the District Land Court decided otherwise and in 1868 awarded title to Eduardo Polloreno for 2,760 acres, including the Sepulveda land.