Published by American Palate

A Division of The History Press

Charleston, SC 29403

www.historypress.net

Copyright 2015 by Frederick Douglass Opie

All rights reserved

First published 2015

e-book edition 2015

ISBN 978.1.62585.405.6

Library of Congress Control Number: 2014953425

print edition ISBN 978.1.62619.872.2

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

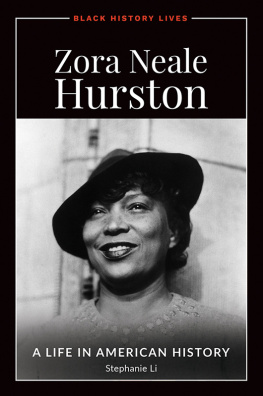

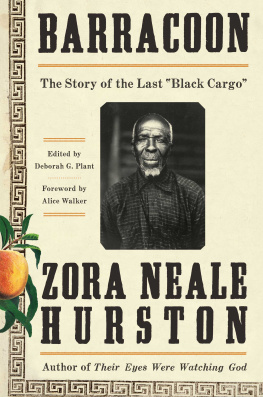

There is enormous variety in American cookery. This book focuses on Florida cooking in Zora Neale Hurstons early twentieth-century ethnographic research and writing. It emphasizes the essentials of cookery in Florida through simple dishes. It considers foods prepared for everyday meals as well as special occasions and looks at what shaped the eating habits of communities in early twentieth-century Florida. It investigates African, American, European and Asian influences in order to understand what they contributed to Floridas culinary traditions.

This book analyzes barbecuing, basting, smoking, roasting, frying and the use of traditional ingredients such as rice, cornmeal, pork, poultry and fish. It also explores the links beyond Hurstons native Eatonville, looking at the people, places and cookery throughout Hurstons literary and ethnographic writings. It studies the cookery of West Florida, Jacksonville and the Everglades.

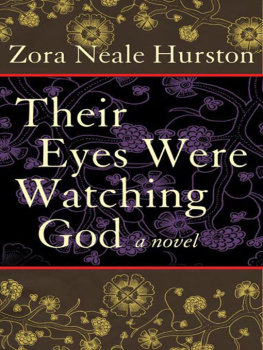

This book builds on the pioneering work of Jessica Harris, Karen Hess, Howard Paige, Sidney W. Mintz, Arjun Appadurai, Pete Daniels, Andrew Warnes and Mark Kurlansky. Like Warness work, this one delves into Hurstons writing, offering a fascinating perspective on African cultural survival strategies in the twentieth century and the culinary links between Floridians and blacks in other parts of the Americas. Warnes focuses on Their Eyes Were Watching God and Eatonville, making no comparisons to the cookery in West and Central Africa. This book makes comparison with food history gathered from a number of sources. Warness analysis focuses only on barbecuing and basting. This books emphasis is more expansive, analyzing various cooking methods. It also considers Hurstons discussion of food in Florida in the context of West and Central African culinary history, and it parallels Hurstons foodways with Pete Danielss work on lowdown culture and this authors work on soul.

Daniels argues that lowdown culture is a pleasure-seeking, working-class culture practiced by relatively autonomous single men and womenroustabouts, as it were. These men and women search for high wages and have plenty of time for lowdown leisure, namely eating, drinking, gambling and sexual activity. Soul is the style of rural folk culture. Soul is spirituality and experiential wisdom. Soul is finding a way to endure and survive with dignity. Soul food has been influenced by other cultures and is enjoyed by a global community of historically rural folk.

This book is divided into five chapters in roughly chronological order. The , the final chapter, talks about barbecue as a technique and event and examines the social and political aspects of barbecue that few writers on the topic get into.

Period recipes are shared throughout the book from cookbooks and black newspapers. Such newspapers informed communities about recipes, many of which African American cooks and food writers from around the country collected and tested. Generally, each black neighborhood had a local distributor of black papers who sold subscriptions to the Philadelphia Inquirer, the Pittsburgh Courier, the Chicago Tribune, the New Journal & Guide, the Afro-American and the New York Amsterdam News. These newspapers kept black readers informed about food trends and recipes from Florida and its bordering states. Careful attention has been given to using geographically and historically relevant recipes from cookbooks and historical newspapers to Hurstons life and work and using Hurston passages to introduce recipes, which solidifies their connection to Hurstons writings.

This book evolved from an intensive two-year project. I am thankful to Babson College and those staff and administrators who provided the support to complete the projectparticularly Carolyn Hotchkiss, Donna Bonaparte and Paula Doherty. Thanks also to Henry Louis Gates Jr., the staff of the Hutchinson Center for African and African American Research and my colleagues at the center during my 201213 fellowship year at Harvard University. I learned and continue to learn so much from a brilliant and collaborative group of scholars I worked with during my year at Harvard. Thank you to the research assistants who made important contributions to completing the bookAna Paula Marinovic, Tandra Taylor and Rachel Taylor. And as a writer with ADHD, special thanks to my editors, Tracy Quinn McLennan and Cynthia Ramnarace. Research for the book was done at Harvard, the special collections at the Beinecke Library at Yale University and the Library of Congress. I spent my fellowship year writing at Harvard and completed the first draft of the book in one year. My productivity was aided immensely by the excellent research assistants and editors I collaborated with who allowed me to crank out chapter drafts and make revisions.

Chapter 1

A HUNK OF CORN BREAD

Zora Neale Hurston was born in wintertime, the season when southerners butchered hogs and harvested sweet potatoes. One of the first voices she heard was that of a white man calling, Hello, there! Call your dogs! But what follows isnt the story youd expect from the late nineteenth-century Jim Crow South.

As a child born in Alabama, Hurston heard the story of a white man of many acres and things, who knew the family well, [and] had butchered [some hogs] the day before her mother went into labor. Knowing that Papa was not at home, and that consequently there would be no fresh meat in our house, he decided to drive the five miles and bring a half of a shoat (a young pig), sweet potatoes, and other garden stuff along. He was there a few minutes after I was born, writes Hurston. Seeing the front door open, he came in and announced his presence in what Hurston called the regular way to call in the country because nearly everybody who has anything to watch has biting dogs.

Nobody responded, but he heard the newborn crying. He shoved the door open, rushed in and followed the sound until he found Hurstons mother, Lucy Ann Potts. The umbilical cord was still attached. Being the kind of a man he was, he took out his Barlow knife and cut and tied the umbilical cord, writes Hurston.

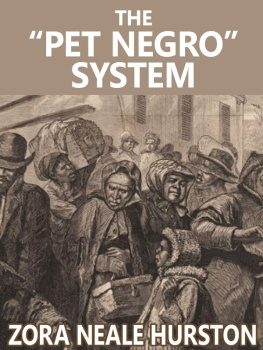

Farmers slaughtering hogs, Monticello, Florida, circa 1930. Courtesy of State Archives of Florida, Florida Memory.

Next page