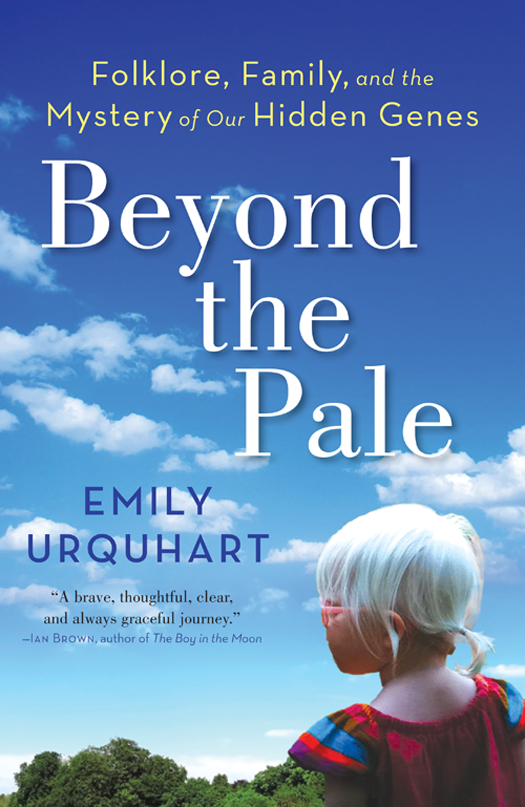

Beyond

the Pale

Folklore, Family, and the Mystery of Our Hidden Genes

EMILY URQUHART

In memory of Rodsella Morse Spencer, who lived not in your time, not in my time, but in the old time, and for Andrew and Sadie, my happily ever after.

M Y DAUGHTER WAS BORN WITH A GENETIC CONDITION I KNEW NOTHING about. It was so foreign to me that I wasnt able to recognize or see it. It is a deceptively obvious medical mystery, one that crops up in both holy and medical texts and in supernatural beliefs across time. In some cultures, people like my child are revered; in others, they are seen as harbingers of evil. In my own society, they have been fodder for legends, believed to live in backwoods colonies, cloistered together, insular and removed. In the recent past, theyve been exploited and exhibited like animals in a zoo. The most extreme stories are from East Africa, where people are being murdered and mutilated for bearing this disorders recessive traits.

I study folklore, the intimate truths we reveal through the stories we tell. Legends, fairy tales, and beliefs are the screens onto which we project our fears, hopes, secrets, and desires. After my daughter was born, I felt that knowing the cultural tales about people with her condition, whether they were frightening or beautiful, would help me understand the shape of her life. Because she will encounter these stories too: on the silver screen, via the Internet, in the news, and from the lips of unpredictable strangers.

Ive never met or known about anyonefamily or acquaintancewho shares my daughters difference. It can pass silently on from parent to child for hundreds of years, so I also didnt know where it came from. Then, a few weeks ago, there was a clue. A series of family photographs from the early 1900s show two women who bear a striking resemblance to my daughter.

I mined archives and census records to learn more about these people, but none of those fraying documents could identify them, or provide the human details I craved about their lives. Specifically, I want to know if these long-ago women were happy, despite living with a disability and standing apart from their peers because of their unusual, if beautiful, appearance. Its a risk-laden query because the answer will shape how I see my little girls future.

Now I am meeting a distant relative I discovered while trying to understand my daughters inheritance. At age ninety, shes the only connection I have to several women who lived a century ago, tangential ancestors whose lives might illuminate my childs present. My dad is driving me to this meeting; he has never met this relative either. He is calm; I am nervous. Neither one of us knows what to expect.

I tell my dad that weve passed the building. We drive around the block, then pull into the parking lot of a modest retirement residence where our cousin many times removed is expecting our arrival. My dad sits patiently by my side while I shuffle and reorder the family photos I brought with me. I think back to when Id sat in a different car, in a colder season, years and miles from here, parked outside our doctors office in Newfoundland. I wept in the passenger seat while my husband stared wearily out from behind the wheel. Our infant daughter was in the back, wearing thumb-less mittens and a tiny woolen hat. She was two weeks old. During our first visit, the physician quelled my husbands fears, but on that day, our second trip to her office in a week, she acquiesced and referred us to a specialist with a long wait-list.

Id looked out the car window and spotted a speck of steel in the gray sky. A plane rising. I wished I were on it. Turning back to see my sleeping infant, I crashed to earth. I resolved to stay there. Although we didnt know it then, inside that car, sitting in the frozen, snow-crusted parking lot, some of the answers were within us, in our cells, soon to be extracted from our blood.

Over the next three years, we consulted a slew of expertsmedical, cultural, regular, and extraordinarybut the person who would teach us the mosttiny, mute, sleeping in the back seatwas our daughter. The rest we uncovered over a series of journeys. These voyages took us across North America and as far away as Africa. Each one was more harrowing than the last, and each time there was a moment when I contemplated retreat before heading forward.

Today, in autumns pale light, my hesitation evaporates. I turn to my dad, who has been waiting quietly for my lead.

Im ready now, I tell him, then open the door and step outside to meet my daughters past and her future.

ONE

DISCOVERY

T HE VISITORS COME FROM ALL WARDS OF THE HOSPITAL. THERE IS AN audiologist, a social worker, a lactation consultant, a rotating cast of doctors, and an endless stream of nurses. We have a private room, but our newly formed family of three is rarely alone. This is not unusual in the maternity ward. What is curious, however, are the nurses who visit with no service to offer. They arrive at my side, somewhat apologetically, to catch a glimpse of our newborn daughter. Some white, they whistle and coo into her plastic bassinet, using the vernacular emphasis that has become so familiar during my five years in Newfoundland. They say it to me, and they repeat it to one another: That hair is some white.

Sadie Jane is born in the usual excruciating manner on Boxing Day 2010. Overdue, she is unwrinkled and chubby, with perfectly formed features and a shock of white hair on her head. Her mouth a tiny O and her arms flailing, she reaches constantly for my arms, my milk, my warmth. Her eyes flutter open occasionally, but mostly theyre shut. In one of our babys fleeting moments of wakefulness, the ward pediatrician probes her pupils with a tiny flashlight. Afterward, she looks past me and my husband, Andrew, past my parents, fixing her gaze on the spruce-clad hills behind the hospital. You have a very fair, very healthy baby girl, she says. We never see that doctor again.

My child is the fairest of them all. The weight of my pride is unbearable, too big for our tiny room on the maternity ward. I stage a photo shoot on my bed, and Andrew takes the picture that will become Sadies birth announcement. I beam the image across the globe.

The next day, Andrew takes Sadie in his arms and goes for a walk down the hall. The nurses crowd around, making a fuss over her white hair and scolding him in the same breath. No walking with babies in the hall! That hair! The liability! He is heading back to our room when he overhears one of the nurses ask, Is that baby an albino?

They return trailed by a heavy-set nurse with dark hair and few teeth. Is she an albino? the nurse asks, lisping slightly, a note of alarm in her voice. No, I tell her firmly. The woman stares back at me, bug-eyed, bewildered. Then she lets herself into our bathroom, where she cleans the toilet, empties the trash bin, and wipes down the sink. She is wearing nurses scrubs, but it is clear now that she is a janitor.

As Andrew recounts this strange tale to his mother over the telephone her heart sinks. She doesnt know what to say, because both she and Andrews father, Don, asked the same question when they saw the first photographs of their granddaughter. Don, a family physician in Georgetown, Ontario, grows increasingly tense as the days pass.